Architects on Architects

Lever Architecture and Field Operations Marries the Pastoral to the Corporate for NBCUniversal’s L.A. Campus

Los Angeles

On a ridge behind the Hollywood sign, there’s a lone pine growing up from a bald dirt patch that locals call the Wisdom Tree. Los Angeles may be a city with no center, but this spot marks a split in the city’s media economy. To the south is the L.A. we know from tourist pictures: Hollywood, downtown L.A. beyond it, and—on a clear day—off to the right, a glimmer of ocean. To the north is the Valley, which is a place we all know even better, even though almost none of us know we know it. It is the place where content is made that all of us will later consume on screens big and small.

So, to the south, the image of Hollywood. To the north, the machine that makes the images. It is a machine so incomprehensibly scaled and shaped that it can only be seen from miles off and a thousand feet up—clusters of offices and soundstages that are themselves as big as city blocks, grouped by corporate history into Television City, Warner Brothers, and Universal City. The last of these is the site of a competition launched in 2017 by NBCUniversal with a brief that seemed to acknowledge a problem, as old as Modernism itself, of how the size and shape of its machine could be made more congenial to the people who worked inside it. The campus was huge but had no obvious places to gather. Company employees were by definition creative, but the facility itself was seen as characterless and hostile to creativity. The machine and its inhabitants were at odds. How, the brief asked, could architecture intercede to make one fit the other?

A version of this imperative has produced the major works of Constructivism, Futurism, Metabolism, the British High Tech, and Deconstruction. The project completed at Universal City by Lever Architecture and the landscape firm Field Operations, the winners of the competition, models a new category worthy of inclusion on the list. We nominate it Corporate Pastoral.

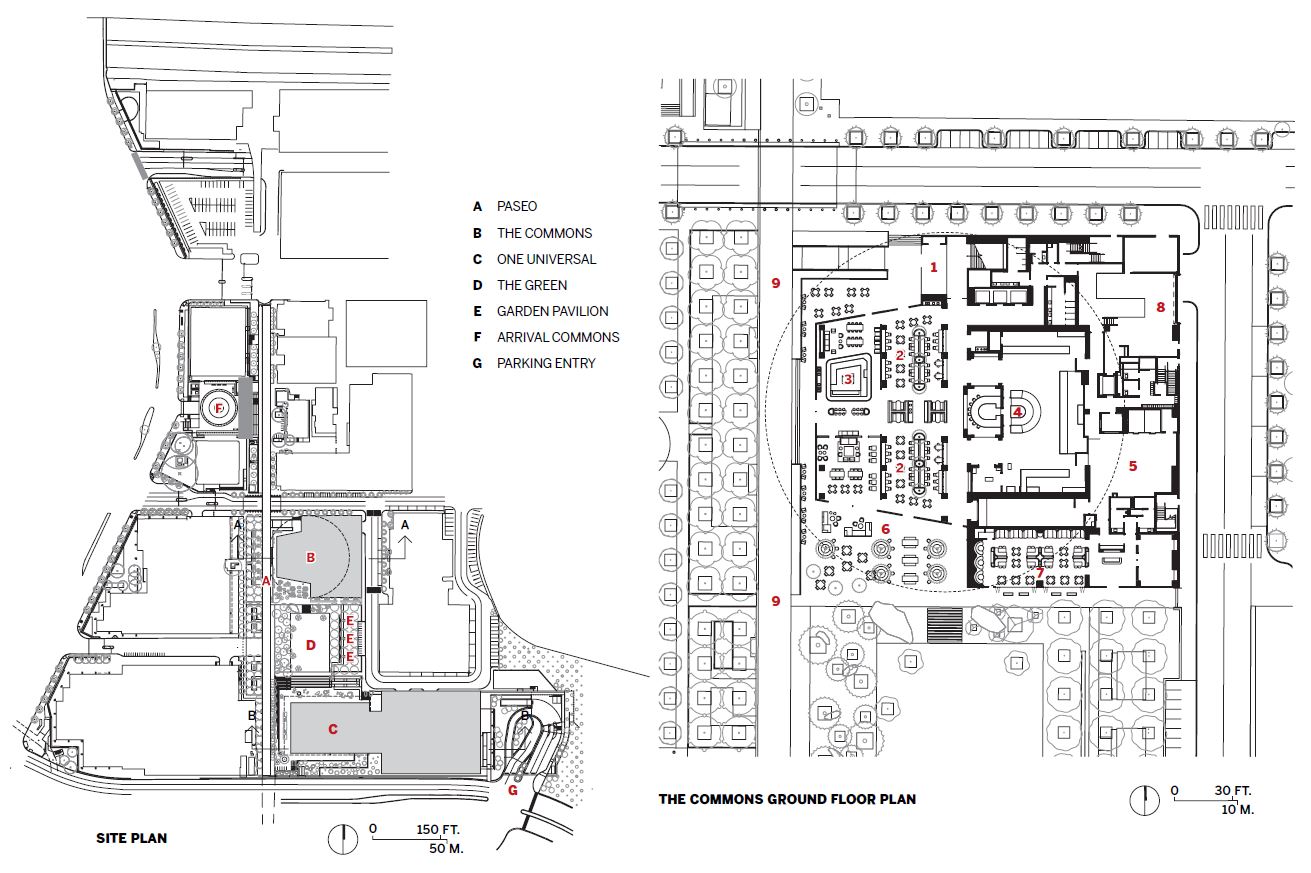

The first rule of this mode is to make a space separate from the city but still connected to it. (The pastoral is not utopia. One must be able literally to reach it.) Lever and Field Operations accomplished this by remaking the western edge of Universal City, where it butts up against the rest of L.A. along Lankershim Boulevard. This used to be a ragged wall of buildings in no particular order—a black office tower and its flatter twin, some soundstages, and something like a mall joined by gates to the campus beyond. At the midpoint of this wall, the designers inserted a block-sized arrival zone around a circular fountain. As people leave their cars and transition to foot, they are lined up with an interior walk, called the “paseo,” that runs parallel to Lankershim but works according to a completely different set of rules. Whereas the boulevard is car-based, open to the city, and transits a homogenous urban sprawl, the paseo is the inverse: it’s mostly pedestrian, separated from the city in a canyon of buildings, and it transects an ingenious series of designed episodes on its run north to south. Near the arrival fountain there is a succulent border garden with a canopy of Palo Breas trees. Farther on is a zone of Western sycamores, a riparian tree species, among native grasses like Bouteloua gracilis planted between the two major new buildings of the project—first, The Commons, ringed in a white screen, filled with restaurants and screening rooms, with an event space and open terrace above; then, One Universal, an office building massed in glassy blocks.

1

2

The glazed One Universal (1) and luminous Commons (2) are connected via The Green and the pedestrian-oriented paseo (3). Photos © Ema Peter, click to enlarge.

3

The paseo is a pedestrian path through the campus. Photo © Ema Peter

The second rule of the Corporate Pastoral is to make an entire world in this newly separate space, following the logic of rural cultivation in lieu of urban commerce. Here that world is made by a shift in orientation. Although the paseo is plotted flat in plan, the relation of building to landscape makes the experience primarily vertical. Even as one traverses the distinct scenic episodes of the paseo, there is a stable order of three fundamental layers. The first of these, obviously, is the ground itself, which becomes an ethical statement. Ground here is productive, verdant, and good. A kitchen housed below grade underneath the Commons makes food for the campus catering system. The planting plan features a little generic lawn grass but is mostly species that thrive in the semi-arid conditions of southern California. The ground is not passively flat but modeled in low relief with a series of helpful articulations, like a broad ramp as the primary connection between the paseo and the Commons and a plinth of landscaped steps that rise up in increments to meet the lobby of One Universal and double as benches.

The second layer we can only call a horizon. It is perhaps strange to say that an enclosed campus would have a horizontal extension of view, but here landscape and building conspire to create one. The lobbies of both new buildings are handled in ways that extend views almost to their respective cores.

A suspended circular scrim delineates various outdoor spaces. Photo © Ema Peter

At One Universal, the transparent lobby is pushed back under a projecting office block, while at the Commons a similar depth is made by suspending a circular “veil” outboard of the envelope. Between these buildings, tree canopies continue the ceilings of the two lobbies, so the horizon becomes volume with floor and lid—one scaled to human occupation but also to smaller, non-urban uses. The designers call the small-scale eating areas and social spaces at the edge, where the paseo touches major building blocks, “porches” and “verandas.” A series of freestanding conference rooms are styled as pristine Modernist cabins nestled back from the paseo in taller grasses. Each of these devices in its way holds creative employment in an analogy to the almost-rural, to roaming, to casual repose, to the size of the body, to near-solitude and chance encounter.

4

The campus has plenty of spaces for people to meet, including lobbies, lounges (4 & 5), and terraces (6). Photos © Ema Peter

5

6

Louvers shade facades with greater solar exposure. Photo © Ema Peter

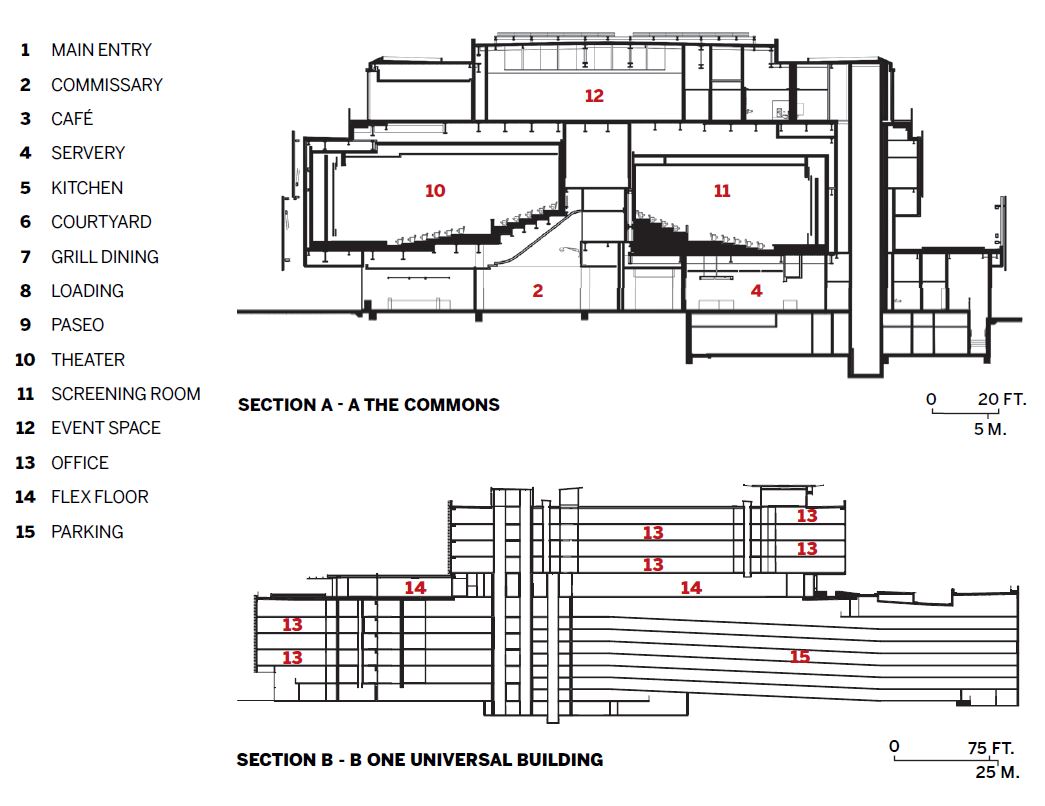

Above it all is the sky, which begins around the second floor. At this height, the building skins no longer extend view but do sky-like, scene-making things. The north-facing elevation at One Universal is a mirror-like wall that grabs the sky’s reflection and situates it as a backdrop. Expressed horizontals in the curtain wall system amplify the effect, banding the image in gradient layers. By contrast, the envelope of the Commons works more like an atmosphere, using a crescent-shaped cross section on the louvers to amplify shifts in light. In both buildings, the program at this stratum is ordered according to the logic of being “up” or deliberately removed from the open zone below. Private and more rarefied executive offices are here, as are state-of-the-art screening rooms. Handsome wood interiors are handled in slats or panels with broad spacing, as if to emphasize the delicacy of connecting, with details that are set in, hung from, or placed atop. At the very apex of the Commons, a terrace for special events befits a cloud top.

Ground, horizon, sky. It’s an order more commonly found in paintings by Poussin, where urbane figures make music or converse on rural terrain against an azure backdrop, demonstrating that sophistication flourishes only when bracketed off from the literal presence of the city. Pastorals serve what they exclude. This is the contribution of NBCUniversal to the lineage of architecture that fits machine to human. It is not a machine in the garden, à la Corbusier’s Villa Savoy. It is not Jacques Tati’s Playtime, steel and glass of machine turned inside out. It is not British High Tech, which trades on the allure of machinery hidden behind implacable surfaces. Nor is it the version of the machine proposed by Rem Koolhaas/OMA on this same site for Universal before its merger with NBC, although that unbuilt scheme, despite its superficial differences, is the most relevant precedent. Like Lever and Field Operations, OMA pitched its work at the scale of an urban intervention. But it also equated creativity with a frisson of urbanity, which they would try to instill in the Valley sprawl. “Creativity needs an elusive dose of order and chaos, fixity and improvisation,” OMA said, and proposed an entire city-in-a-building of four towers spanned by a beam of offices.

Now the mood has flipped. Cities? Too much disorder and disease. Creativity? It needs rest. Constructivism, High Tech, Deconstructivism, and other Modernism may have delighted in confronting the creative worker with the presence of the machine, but now the imperative is less violent, and, with this, the door has opened for Lever and Field Operations to enjoin a starkly different model. Instead of the theatrical, exteriorized urbanism of OMA’s project, the incongruities of scale and form between human and machine at NBCUniversal are compressed to the management of edges. The projections and intrusion of the corporate works tend the edge of a pleasant scene, constructing its sky, opening a plenum for idyll, coaxing productivity from its ground. The order verges on cosmological. Companies tend their flocks. Only God above and the devil below are missing.

Back up 1,000 feet, behind the Hollywood sign, the Wisdom Tree now seems a parallel gesture to the NBCUniversal redesign, albeit with impoverished means. It too orients a whole system of significance. People stack rocks in memoriam around it, plant flags to remember 9/11, and leave notes of wisdom. The gleaming white and green stretch below is magnificent in its attempt to do this at the scale of urbanism. The question now is whether the machine and its mediation in architecture will continue to supply the meaning we seek to instill. This is a story of permanent mismatch, where the role of architecture is always to render safe the contact between industry and humanity and, in so doing, make a reassuring myth, whether that is the frisson of OMA’s proposal or the ordinal sureties of Lever and Field Operations’. Does the security of the pastoral need to originate as a helpmate to corporate power? Or can some other force—perhaps some new formulation of a public—catalyze this work?

Click plans to enlarge

Click sections to enlarge

Read our entire January 2025 “Architects on Architects” series.

Credits

Architect:

Lever Architecture

Architect of Record:

House & Robertson

Engineers:

WSP, Englekirk Structural Engineers (structural, One Universal); Thornton Tomasetti (structural, The Commons); AMA (m/e/p); Langan (civil); Shannon & Wilson (geotechnical); Gibson Transportation (traffic)

Landscape Architect:

Field Operations

Consultants:

Studio Shamshiri, AvroKO, Gensler (interiors); Atelier Ten (sustainability); Salter (acoustics); Horton Lees Brogden (lighting); Arup (fire safety); Thornton Tomasetti (envelope); Fisher Dachs Associates (theater consultant); Aurora Development (project management)

General Contractor:

Hathaway Dinwiddie

Client:

NBCUniversal

Size:

84,000 square feet (The Commons); 350,000 square feet (One Universal)

Cost:

Withheld

Completion Date:

September 2024

Sources

Curtain Wall:

Kawneer, Arcadia

Doors:

Nanawall

Hardware and Entrances:

CR Laurence

Fixed Seating:

Poltrona Frau