Architects on Architects

At MIT, SANAA Shapes a Music Building Among Midcentury Icons with Respectful Irreverence

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Architects & Firms

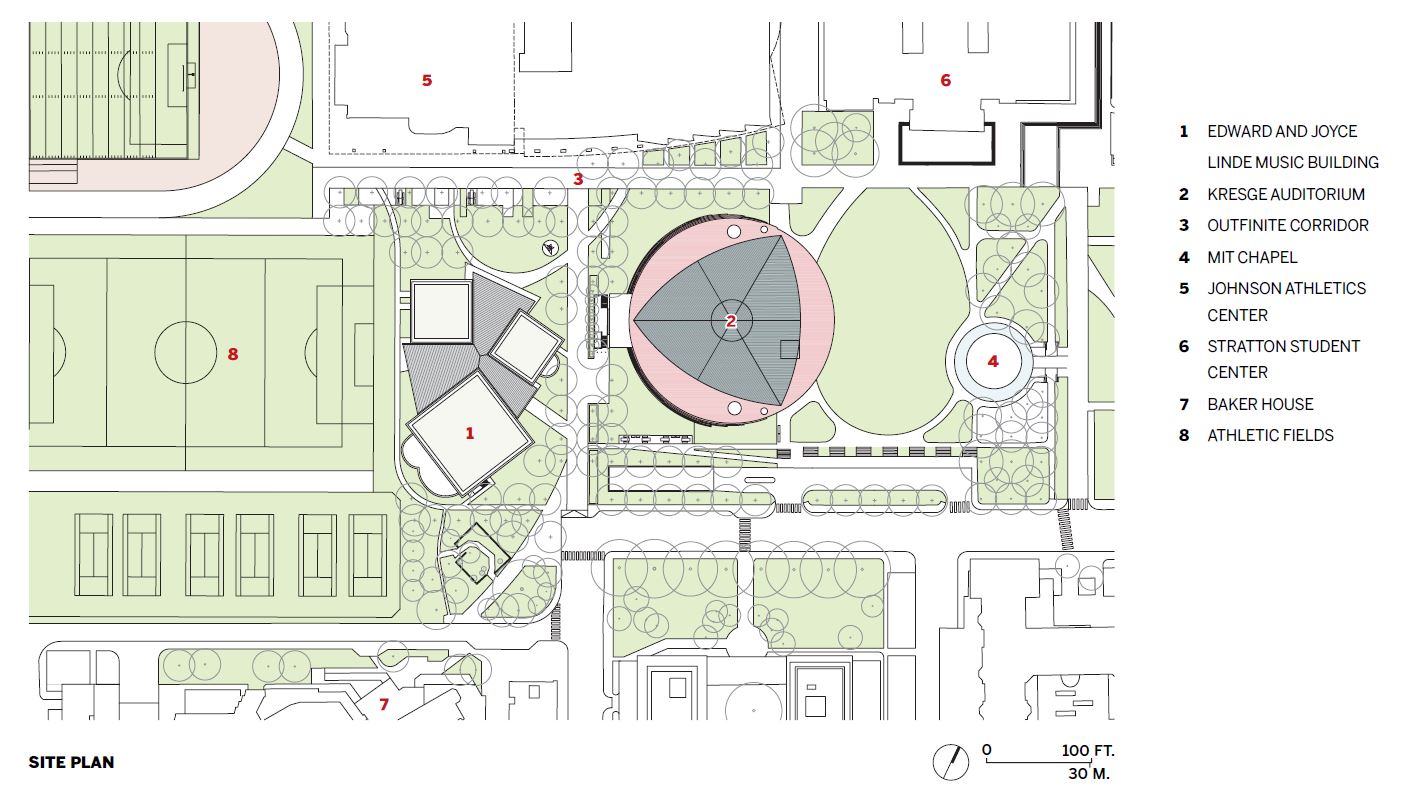

SANAA’s much anticipated Edward and Joyce Linde Music Building officially opens its doors to the public next month—for Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa, their fourth building in the United States. Situated on the MIT campus, it extends westward the Infinite Corridor—what is colloquially known as the Outfinite Corridor—on axis with MIT’s historic entrance on Massachusetts Avenue. Effectively, this area comprises what is possibly the most memorable 20th-century contribution to the campus, with Eero Saarinen’s MIT Chapel and Kresge Auditorium (both 1955) framing the Kresge Oval, a public lawn with Eduardo Catalano’s Stratton Student Center (1963) to its north, and Alvar Aalto’s Baker House (1949) just southwest, making for a formidable Modernist context.

The volumes of the new music building are set between Aalto’s Baker House and Saarinen’s Kresge Auditorium. Photo © Ken’Ichi Suzuki, click to enlarge.

If Saarinen had gotten his way, the chapel and auditorium would have been framed within a master plan of his own making, a larger quad encircled by a thicket of trees on three sides and an institutional building fabric on its western edge, a bookend bringing the academic campus to a terminus facing the sports fields. Of course, history would veer off this path, and, instead, SANAA would inherit the western flank, alongside the athletic complex. Providing an academic home for the music program—the first campus building dedicated solely to music—the siting of SANAA’s project is critical. Adjacent to Kresge Auditorium, this allows for the creation of a Performing Arts hub for MIT at large.

1

The arches of Kresge Auditorium, in the background (1) and foreground (2), are seen in relation to those of SANAA’s building. Photos © Ken’Ichi Suzuki

2

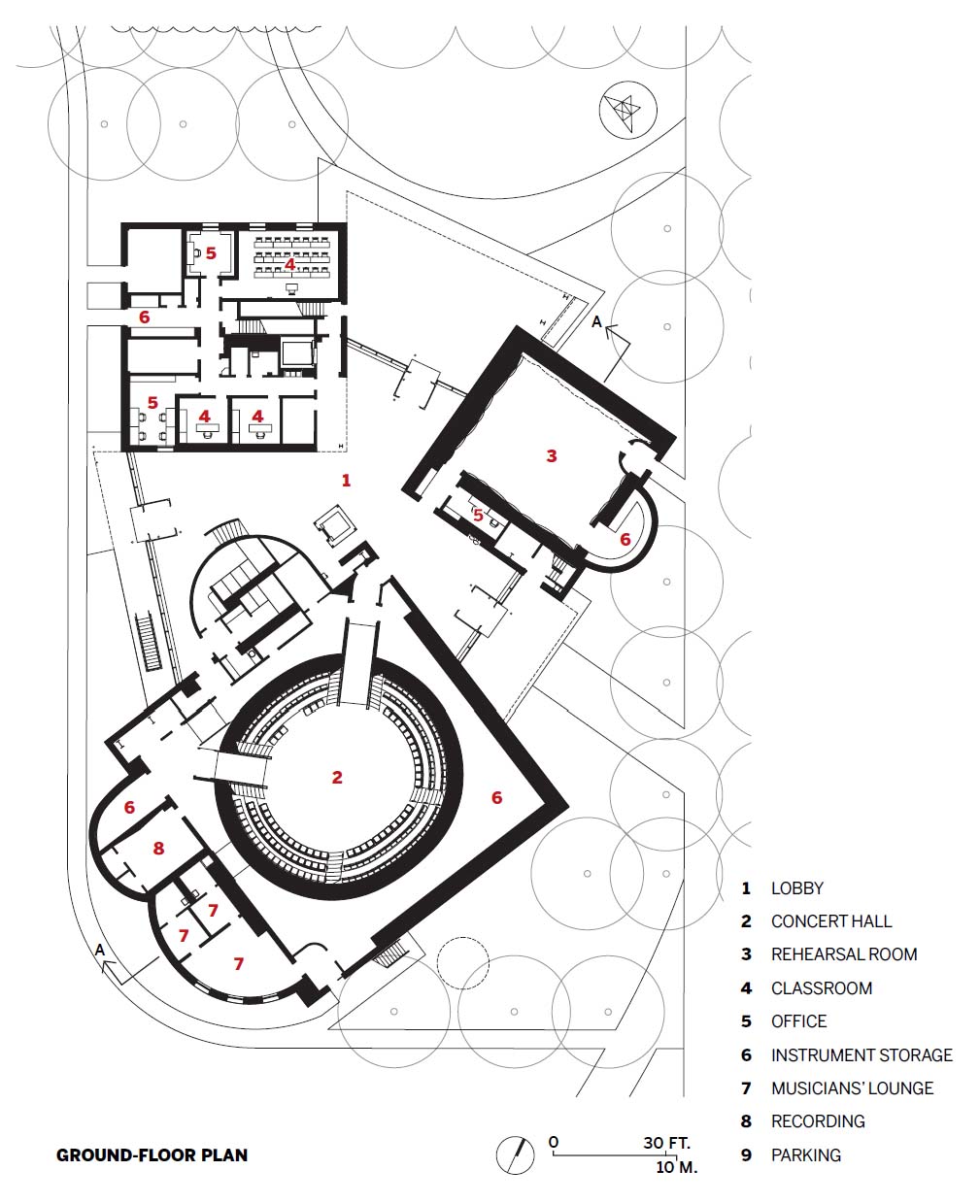

SANAA’s most memorable contribution to MIT is its response to Saarinen’s intended master plan, not so much framing the quad with the backdrop he had envisioned but rather designing an “object building,” whose configuration has the capacity to orchestrate a sophisticated urban-design narrative within. The music building absorbs the ambulatory complexity of the campus by acting as the fulcrum through which the students circulate toward their ultimate daily destinations: the dormitories to the southeast and northeast of the sports fields. The circulation of the building is defined by a Y-shaped figure that draws in two diagonal prongs on the east connecting to the campus, and a third prong on the west, framing an expansive view of the sports fields. The porosity of this promenade is all the more important, given the necessary insularity of the building type. The urban strategy is further enhanced by Reed Hilderbrand’s landscape, layering trees within a middle ground, helping to mediate between Saarinen’s auditorium while punctuating the episodic nature of the promenade.

If SANAA’s composition would seem like an urban-design contrivance—embodying the potent scenographic strategies of Galli da Bibiena, but here relieved of the mannerism of his surfaces—then one must also consider the challenge from a programmatic perspective. The division of the building into three volumes within the negative space of the Y stems from a fortunate acoustic mandate requiring sound isolation among the three key functions of the program: Thomas Tull Hall (a concert hall), the Beatrice and Stephen Erdely Music and Culture Space (a rehearsal room primarily for percussion), and the Jae S. and Kyuho Lim Music Maker Pavilion (composed of practice rooms, classrooms, a makerspace, and offices). Polemically breaking with the formality of Saarinen’s icons on the east–west axis, the triad of brick volumes functions as a still-life of sorts, with an animate silhouette that mirrors the programmatic blocks and visually dissipates the monumentality of MIT Chapel and Kresge Auditorium with an architectural “breakwater”—allowing the axis to disperse through the cracks of SANAA’s clay monoliths.

The concert hall seats close to 400 around a central performance space. Photo © Ken’Ichi Suzuki

A rehearsal room hosts musicians on percussion instruments. Photo © Ken’Ichi Suzuki

Courageous in the risk this strategy entails—effectively extending Saarinen’s axis with a third object, albeit aggregated as an assembly of parts—SANAA deftly confronts the dilemma of reverence and irreverence that is the inevitable challenge its contribution poses. Though sculptural in its massing, the adoption of redbrick cladding invariably forces the building to recede as part of its context, inconspicuously forming an extended brick tapestry of 270 degrees, from MIT Chapel, Maseeh Hall (1901), and Baker House all the way around to Davis Brody’s Johnson Athletics Center (1981). In other words—despite its formal exuberance, the music building serves as a Band-Aid, bridging the gap on its western flank and creating an extended backdrop for Kresge Auditorium—ensuring that it remains the most dominant figure in the urban space. Stealth in its materiality, yet articulated in its composition, SANAA maneuvers the building towards a seeming contradiction, a deliberate ambivalence it straddles with some confidence.

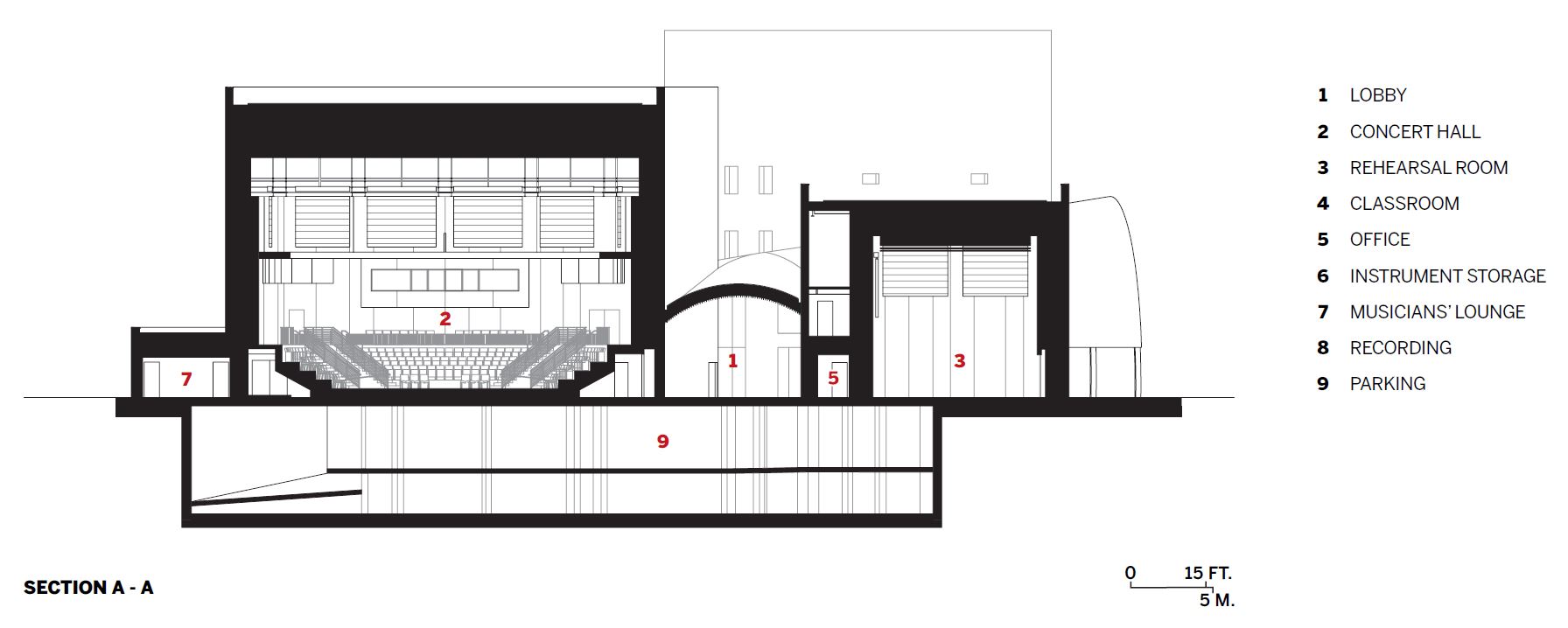

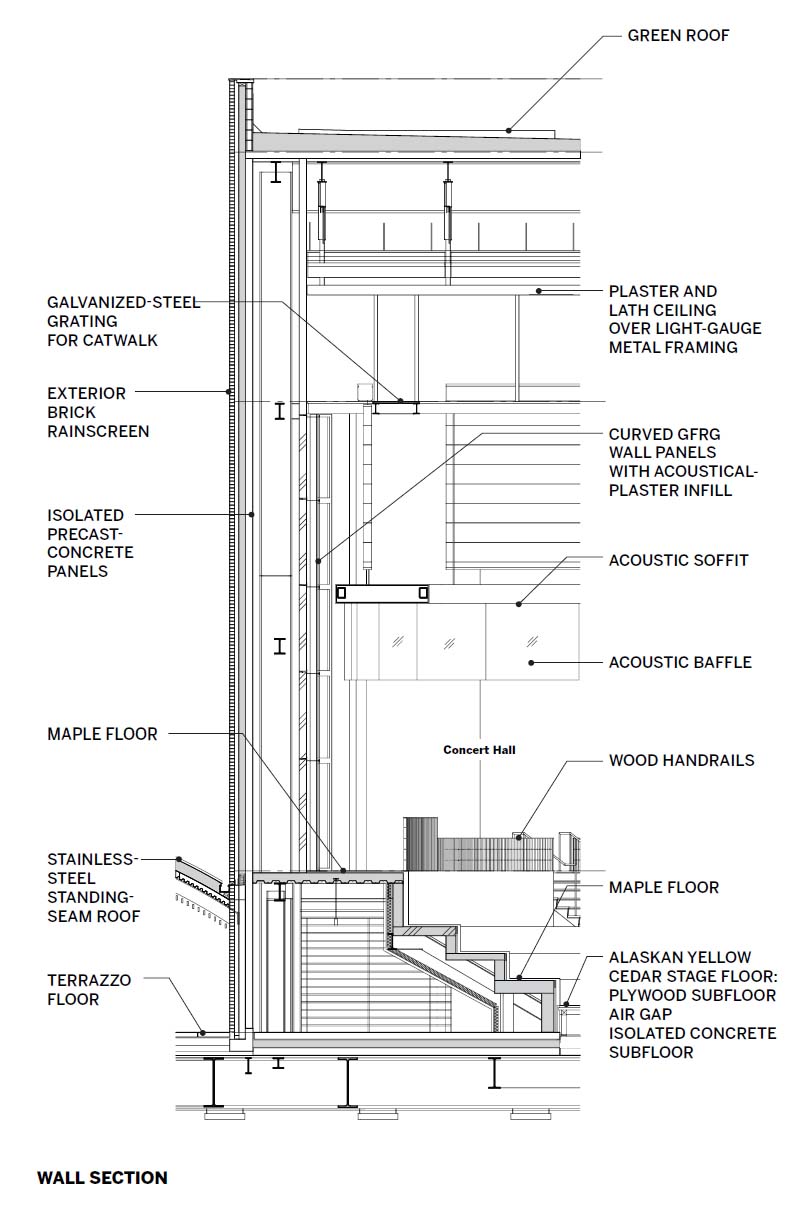

Each volume is built of steel framing with a double shell of precast concrete to ensure full acoustic autonomy. Thus the seemingly random scattering of brick boxes is anything but, and is somehow a semantic embodiment of the inevitable acoustic separation required between the main programmatic elements, in direct orchestration with a strategic urban narrative. As great architects might, their thoughtful collaboration was reinforced, on the one hand, by the acoustic precision of Nagata Acoustics and, on the other, by the leadership of Keeril Makan, an extraordinary composer and associate dean of the school of humanities, who acted as a sounding board for MIT’s varied musical talents. Together, they set their eyes on Frank Gehry’s Pierre Boulez Hall in Berlin, which would serve as a model for the type of flexibility their proposed concert hall would engender. If the mission of the music building was to provide a dignified home for its students and faculty, then how it negotiates its visual and acoustic performance would be balanced out by this expanded team. Beyond the purity of the mute clay blocks, interventions punctuating the massing register a language that betrays hints of recognizable elements: of apses and bays for practice/green rooms, of fluting and striations for surfaces, all formal deformations indicating an escape from the rectitude of the platonic volumes. These formal and geometric tropes address acoustic mitigation, attending to such phenomena as reverberation and resonance, all while embracing the manner in which the forms mediate between the inside and outside, the surfaces and the massing.

All said, the allusive nature of these figures maintains a distance from both typological and iconographic quotations. By their own admission, the architects’ embrace of the radial forms in plan and section was a way to create a dialogue with Saarinen’s chapel and auditorium, two buildings whose languages are distinct in their own right—different scales, materials, geometries, and levels of detail. They nonetheless revolve around a shared formal foundation to which the music building adds a new chapter. With the introduction of the monumental arches (the manifestation of the Y in spatial terms), SANAA takes a turn in its trajectory that is possibly less predictable. The firm’s history of formal explorations commonly maintains a fidelity to abstraction, allusive connections to the landscape, and self-similarity, swerving away from referential overtness. From the main perspective of the Outfinite Corridor looking east, then, one cannot suppress the iconographic bias linking SANAA’s new entry arch to the Kresge vault and the lower arches of the MIT Chapel, all collapsed into one view; here we witness a linguistic dimension in this work, something that is less common in the firm’s oeuvre. SANAA’s own three arches vary in size, scale, and hierarchy, all beautifully converging as a vortex at the center of the lobby; but its main arch, facing the Outfinite Corridor, is also meant to serve as an outdoor rehearsal room, with the conical geometry of the arch containing the sound, all while communicating an ambiguously “gramophonic” figure with semantic range. In the richness of this view, Saarinen, the gramophone, and the acoustic performance of arches meet in what is akin to “a chance encounter of a sewing machine and umbrella on an operating table.”

3

The exterior arches (3 - 5), converge in the interior lobby space (3 & 6) between the three brick volumes. Photos © Ken’Ichi Suzuki

4

5

6

Despite this, the exposure of the curved extruded I-beams, the revelation of the standing-seam metal roofing atop, and the rawness of the building’s expression are so deadpan in their representation that they defy the kind of transcendence one immateriality, of visual ambiguity, and of experiential phenomena, this building remains stoic in its allegiance to material conventionalism, a realism that seeks beauty in the everyday. In the past, the architects have worked painstakingly to hide the evidence of the building’s infrastructure behind the scenes, making things look simple even when the labor of concealment is a monumental architectural task; here, things remain exposed in their exacting organization. Sejima and Nishizawa, in speaking with me, referred to the difficulty of finding the right brick unit for this special occasion, a brick with the versatility of turning corners, navigating radii, and other feats intended to secure its mass. For a curtain wall, they undertook all efforts to maintain the integrity of the brick volumes as monolithic blocks, even if the inevitable requirement of expansion joints compromises the continuity of the running bond assemblage. Still, it is in the specification of things so prosaic that we discover a stubborn adherence to SANAA’s sense of the generic, that also comes through in the matter-of-fact institutional characteristics, elegant and precise as they are, but also explicit in their insistence that the building is “just a building.”

Though this might seem a deviation in SANAA’s path, I think it’s a self-conscious one, where the architects focus not only on visual phenomena as played out through their formal, spatial, and material strategies, but expand their lens to a broader sensorial field. As such, the building’s visual dexterity is not only legible at the urban scale but transformative for the campus at large—and the closer one gets to its surfaces, its interiors, and its details, the more the visual recedes intentionally, displaced by a necessary deference to the auditory. The building’s performance aptly transcends normative experiences within an amplified sonic medium—embracing their rightful audiences, the building chambers eventually find their voice as a series of mellifluous acoustic instruments.

Click plan to enlarge

Click plan to enlarge

Click section to enlarge

Click detail to enlarge

Read our entire January 2025 “Architects on Architects” series.

Credits

Architect:

SANAA — Kazuyo Sejima, Ryue Nishizawa, principals; Yumiko Yamada, Amy Hyemin Jang, Hiroaki Katagiri, Takayuki Furuya, Naoya Harada, Iven Peh, Pat Pongteekayu

Executive Architect:

Perry Dean Rogers Partners Architects

Engineers:

Silman (structural); Buro Happold (m/e/p/fp); Nitsch Engineering (civil); Haley & Aldrich (geotechnical)

Consultants:

Reed Hilderbrand (landscape); Nagata Acoustics (acoustics); SAPS / Sasaki and Partners (structural concept); TheatreDNA (theater); Buro Happold (lighting); Front (facade); Transsolar KlimaEngineering (energy)

General Contractor:

Lee Kennedy

Client:

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Size:

98,650 square feet

Cost:

Withheld

Completion Date:

December 2024

Sources

Masonry:

Cerámicas Mora

Curtain Wall:

Kawneer

Standing Seam Roof:

Bemo

Metal Windows:

Schüco

Concert Hall Seating:

Poltrona Frau

Lighting:

Lucifer

Lobby Baffles:

Gordon