A New Exhibition Surveys the Residential Work of New York Architect Myron Goldfinger

A young Myron Goldfinger (left) and his Norman and Molly McGrath Residence (1976) in Patterson, New York. Goldfinger photo © The Estate of Myron Goldfinger; McGrath Residence photo © Norman McGrath; both images courtesy the Paul Rudolph Institute For Modern Architecture

A month before architect Myron Goldfinger died last year, his wife, June Goldfinger, asked a question she had never posed during their six decades of personal and professional partnership. “Myron,” she said, “what is your architecture about? If you had one thing to say about your architecture, what would you say?” June was struck by the simplicity of Myron’s reply: “He just looked at me and he said ‘Circle, square, triangle.’”

Goldfinger’s gnomic utterance inspired the title for an exhibition on his legacy at the Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture (PRIMA) in New York. Curated by PRIMA’s president and CEO, Kelvin Dickinson Jr., Circle, Square, Triangle: Houses I Never Lived In: The Residential Work of Myron Goldfinger 1963-2008 is on view until March 22, 2025. The exhibition’s subtitle comes from the forward to his 1992 monograph, Myron Goldfinger: Architect, in which Goldfinger recalled the glamorous homes he admired while growing up working class in Atlantic City, writing “I am always building the houses I never lived in as a boy.”

The Gilbert and Marsha Schulman Residence, Montague, New York, designed by Myron Goldfinger in 1977. © Norman McGrath, courtesy the Paul Rudolph Institute For Modern Architecture

Belying this simple, three-shape summation of his life’s work, Goldfinger left behind voluminous archives of his decades-long architectural practice, best known for geometric houses in dramatic beachfront or sylvan settings, many built in the upscale suburbs and vacation towns around New York City. The exhibition draws upon drawings, plans, models, photographs and publicity materials for residential projects built and unbuilt, carefully saved but never properly cataloged. Those archives have moved a mile up Manhattan’s east side, from the Goldfingers’ apartment in the I.M. Pei–designed Kips Bay Towers to PRIMA’s home in Paul Rudolph’s recently landmarked Modulightor Building on East 58th Street.

Myron Goldfinger. Photo © David Michael Kennedy, courtesy the Paul Rudolph Institute For Modern Architecture

The most important donation to PRIMA, however, is June Goldfinger herself. Inspired by PRIMA’s mission to preserve Rudolph’s legacy, June joined the organization’s board and has helped Dickinson sort through the residuum of her late husband’s architectural practice, where she worked as the interior designer on many projects.

That personal touch has allowed the exhibition and archive project to come to life. Dickinson and a score of volunteers are working to digitize Goldfinger’s archives to preserve his legacy and make his work available to scholars, enthusiasts, and the next generation of architects. June thinks Myron would have been thrilled with the choice of PRIMA—Rudolph was his professor at the University of Pennsylvania in the 1950s and, according to June, was one of the only modern architects whose work the Goldfingers followed. Now, Goldfinger is inspiring Dickinson and PRIMA: “We realized that our mission was bigger than Paul Rudolph. There are other architects’ work that is similarly threatened by being forgotten. And so, our mission has grown.”

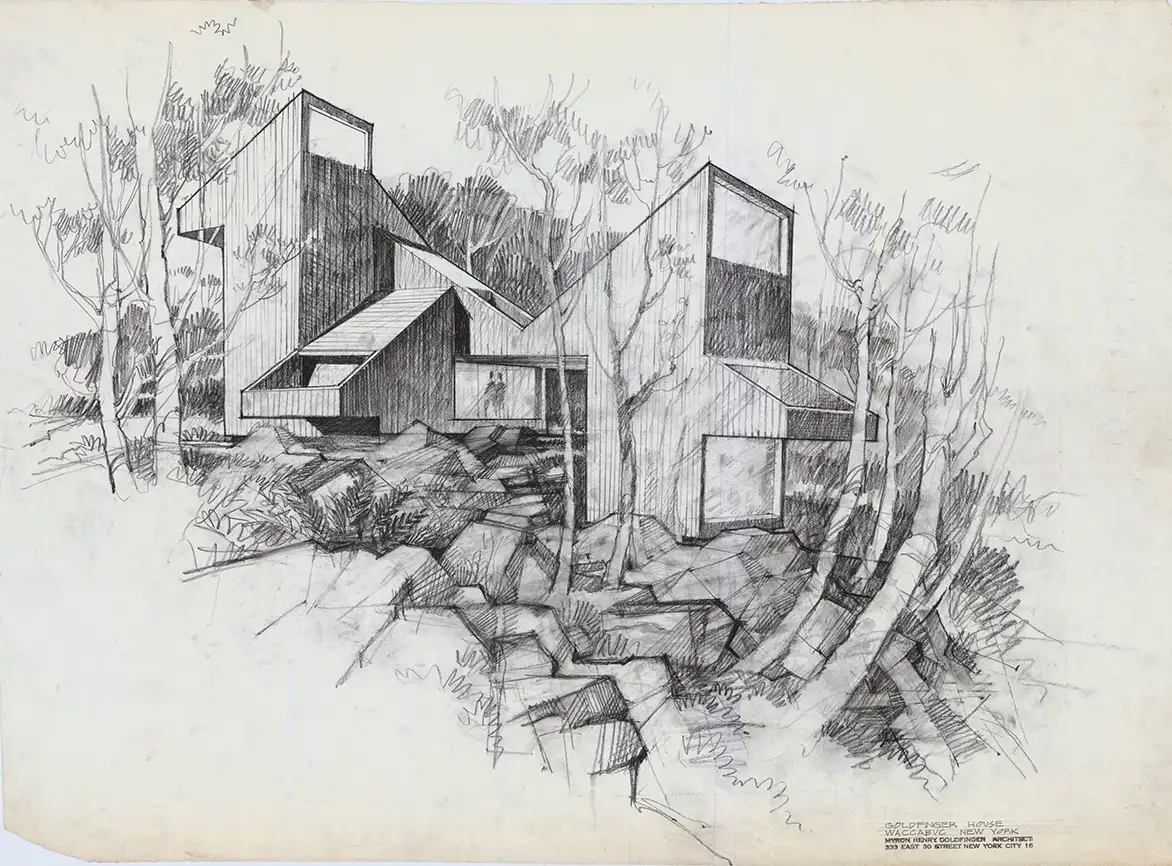

Rudolph’s influence is apparent in the angular, cantilevered triangles of the earliest project in the show, Myron’s house for himself and June in Waccabuc, Westchester County. Built shortly after starting his own practice and his family, June gave Myron carte blanche to design their home, reasoning that this was the first—and last time—her husband would be able to build to his vision free of anyone else’s demands.

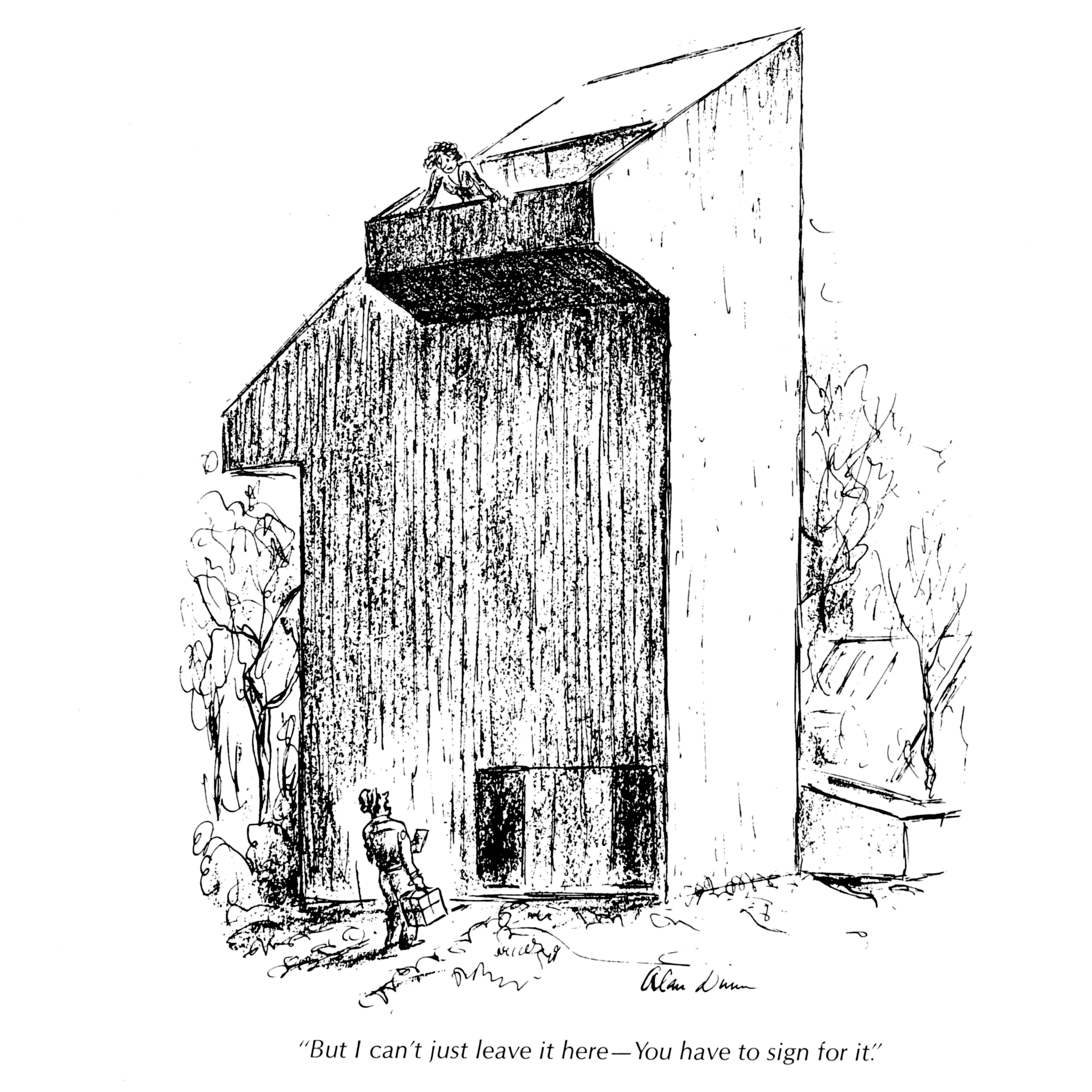

The Waccabuc house made a splash and was published in the Mid-May 1971 edition of Record Houses as part of a feature on houses architects designed for themselves. It gained enough notoriety to inspire parody, with RECORD’s legendary cartoonist Alan Dunn imagining the impasse between a woman on a balcony overhanging the sheer cedar facade as a delivery man pleads with her to come down to sign for a package. As with many of Dunn’s cartoons, the joke’s truth is what gives it bite: omitted from the exhibition’s wall text but documented in PRIMA’s online listing of the project is the fact that upon moving in, June was surprised to find the kitchen on the second floor and even more surprised not to find any space set aside for their baby daughters. Fortunately for the Goldfinger family, Myron’s modular construction (built around the standard size of an 8-by-15-foot sliding glass door) and June’s talent for interiors found space for raising a family in the home where they stayed for over five decades.

1

2

Drawing of the Myron and June Goldfinger Residence (1969) in Waccabuc, New York (1); Alan Dunn cartoon in Architectural Record depicting the residence (2). Images © The Estate of Myron Goldfinger, courtesy the Paul Rudolph Institute For Modern Architecture (1); Architectural Record (2). Click to enlarge.

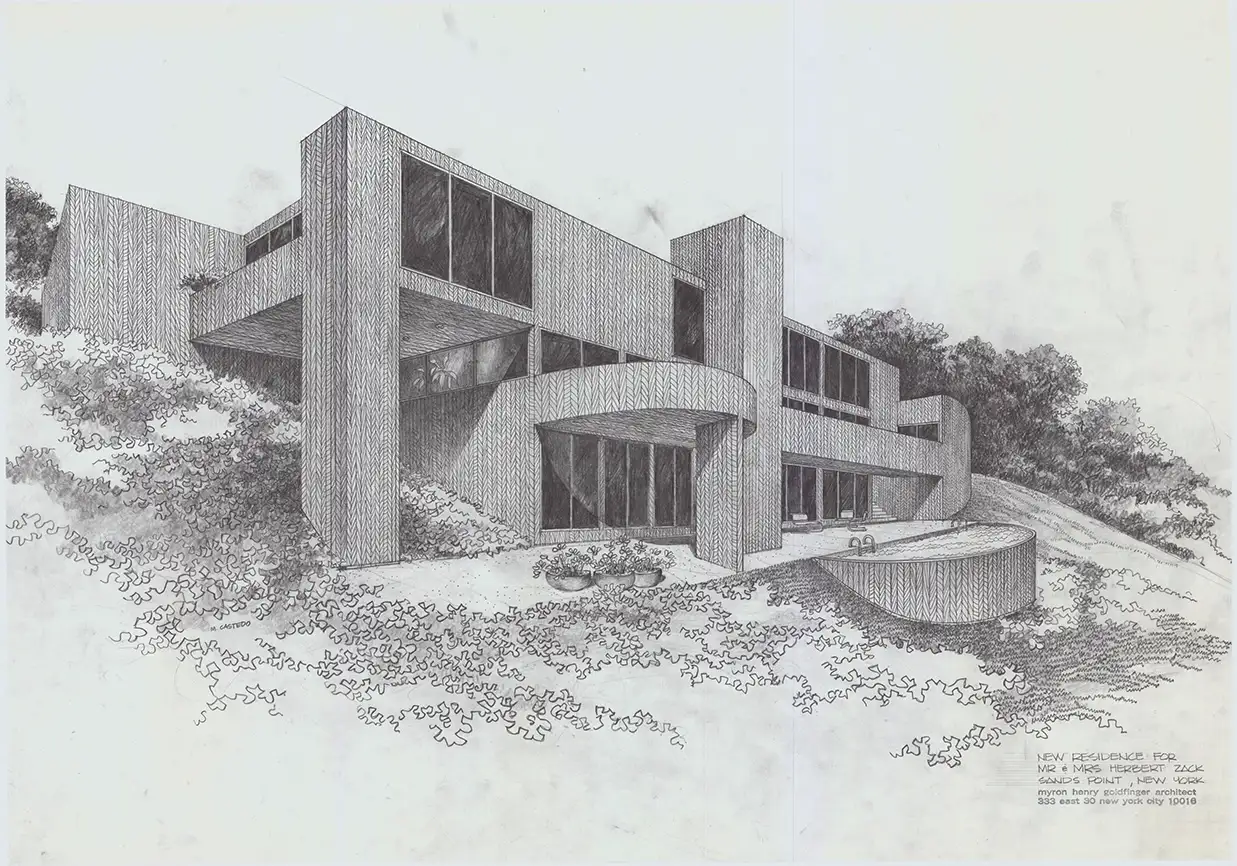

Goldfinger added the circle to his toolbox when building the next project featured in the exhibition, the 1970 Matkovic house. Built for June’s parents in Sands Point on the North Shore of Long Island, the curving forms of the house evoke the boat hulls of his father-in-law’s shipping business. In one of the most personal and lively sketches in the exhibition, Goldfinger illustrates the curving forms of the house. Those looking for the exhibition’s titular triangles will find them not in the house but in its inhabitants, who are drawn in Goldberg’s characteristic renderings as triangle torso-ed. This less-than-idealized rendering of his clients seems not to have upset Goldfinger’s in-laws, nor the many other clients he and June cultivated as friends and repeat customers. Goldfinger benefitted from being able to express his personal vision of architecture in conversation with the individual needs of his clients—which also must have gone a long way towards not forgetting any more children’s bedrooms.

With his three shapes, Rudolph continued designing residences through the 2000s, ranging from New York City apartments to Antiguan resorts. Circle, Square, Triangle features a dozen of Goldfinger’s residential projects. We see the dramatic side of Goldfinger in his renovation of singer Roberta Flack’s apartment in Manhattan’s legendary Dakota building. Goldfinger’s illustration is pure showbiz, with mirrored walls surrounded by round Hollywood bulbs, while his blueprints assure the Datoka’s famously demanding co-op board that “HUNG CEILING SUPPORTS SHALL NOT DISTURB CEILING MOULDINGS” [sic]. The wall text informs us that some of the building’s historic moldings were in fact disturbed, much to the consternation of the architecture critic and (former) Dakota resident Paul Goldberger. The exhibition quotes Myron Goldfinger’s response to the original detailing as “it wasn’t good then and it isn’t good now.”

3

4

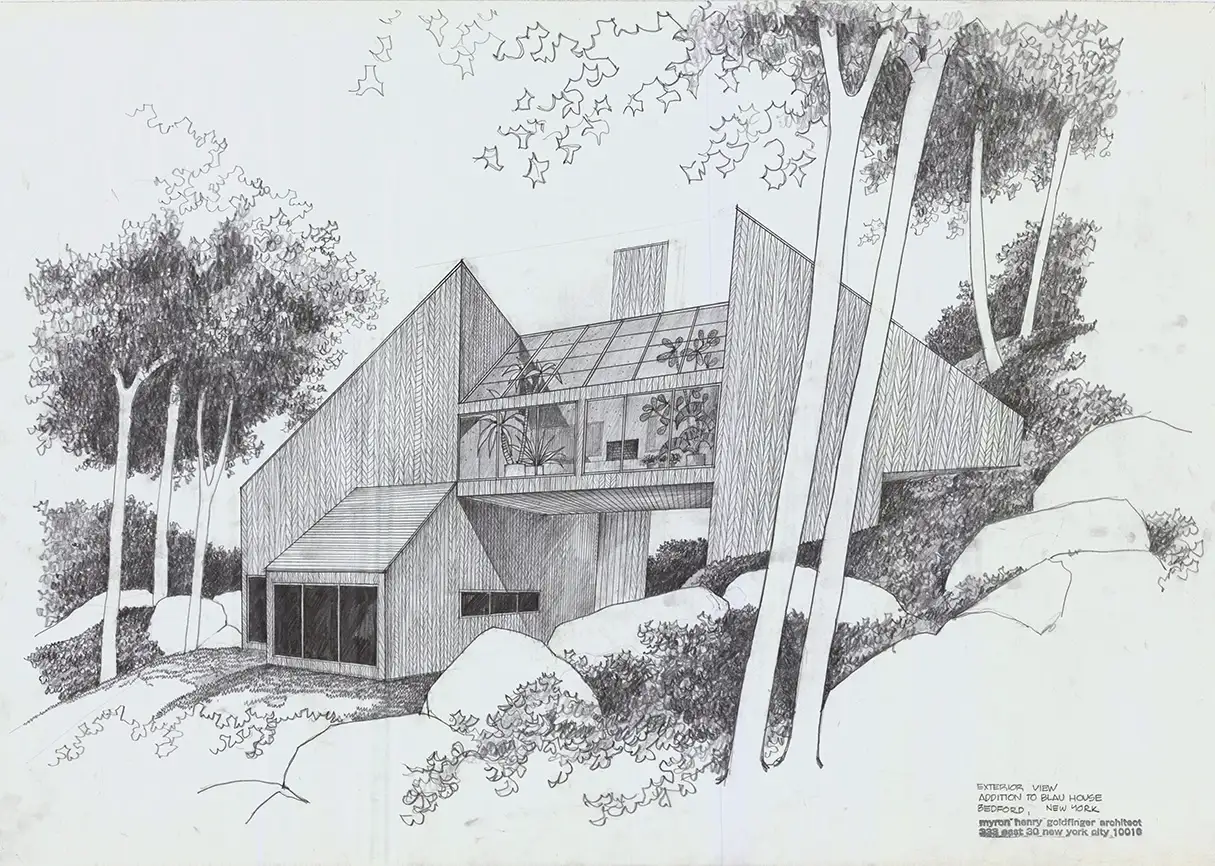

Drawings of the Herbert and Julia Zack Residence (1977), Sands Point, New York (3) and Laura Blau Residence (1970), Bedford, New York (4). Images © The Estate of Myron Goldfinger, courtesy the Paul Rudolph Institute For Modern Architecture

Every project in the exhibition is showcased through a variety of media spanning the design, construction, and domestic life of the building. Hand drawn interior renderings in three-point perspective oozing 70’s glamour are juxtaposed with detailed construction drawings and carefully staged interior photographs. For projects lacking architectural models, PRIMA honored Goldfinger’s legacy as a teacher and commissioned new models from architecture students at the Pratt Institute, where Goldfinger taught for a decade and worked with the eminent scholar Sibyl Moholy-Nagy.

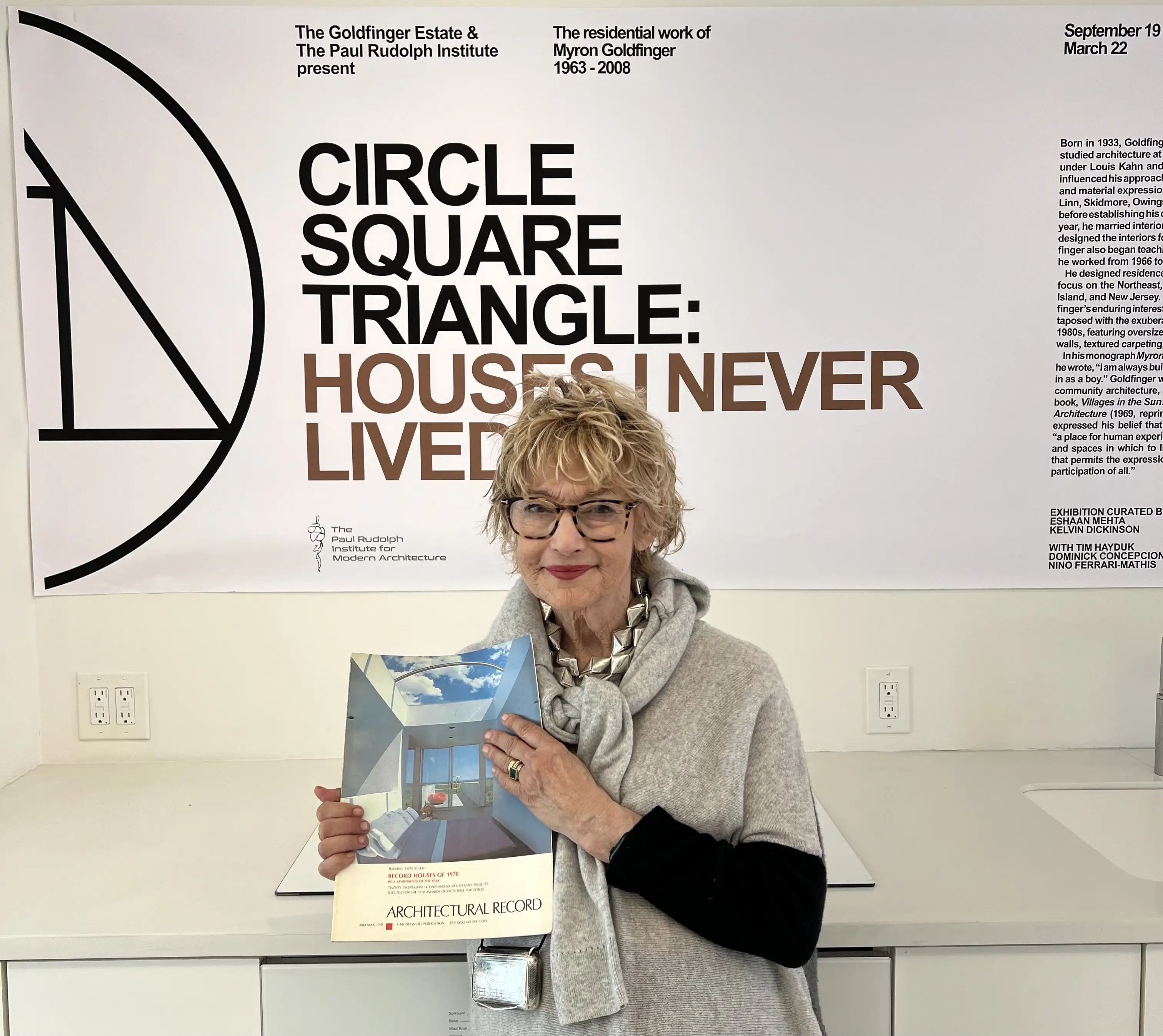

June Goldfinger holds a copy of the 1978 Record Houses issue with Myron’s Marcus House in Chappaquiddick on the cover. Photo courtesy Sam Furnival

The intent of the exhibition is to show the human hand in every stage of the design, construction, and even marketing of these projects. Goldfinger’s human touch and careful eye is something PRIMA’s Dickinson hopes young architects can be inspired by, even in an age of AutoCAD and Generative AI.

Asked to provide her own summation of her husband’s legacy, June emphasizes not the spaces he created but the people who inhabit them. “His architecture really celebrates the occupants. He celebrated people.” With this exhibition of his residential work and PRIMA’s ongoing efforts to archive and share it, Goldfinger's humanistic vision for architecture can be celebrated.

Circle, Square, Triangle: Houses I Never Lived In: The Residential Work of Myron Goldfinger 1963-2008 is on view at the Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture through March 22. A concurrent exhibition, Circle, Square, Triangle: A World I Wanted to Live In. The Public and Unbuilt Work of Myron Goldfinger 1963-2008 is on view at the Mitchell Algus Gallery in New York.