“The Warburg Institute was founded to study the Renaissance,” says its director Bill Sherman, “and ended up changing the way we see the world.” That’s a bold claim but justified. As part of the University of London since 1944, this unique academic center has pioneered the study of culture and society through images, guided by the somewhat eccentric preoccupations of its founder, Aby Warburg. The Institute began life in Hamburg at the turn of the last century before decamping to England as the Nazis came to power, and since 1958 has occupied a purpose-built home in the Bloomsbury district designed by Charles Holden. Though much-loved by scholars, the building had significant defects—from leaking roofs to its lack of public access—which have been addressed in the transformational $19 million Warburg Renaissance Project led by London-based architect Haworth Tompkins.

1

2

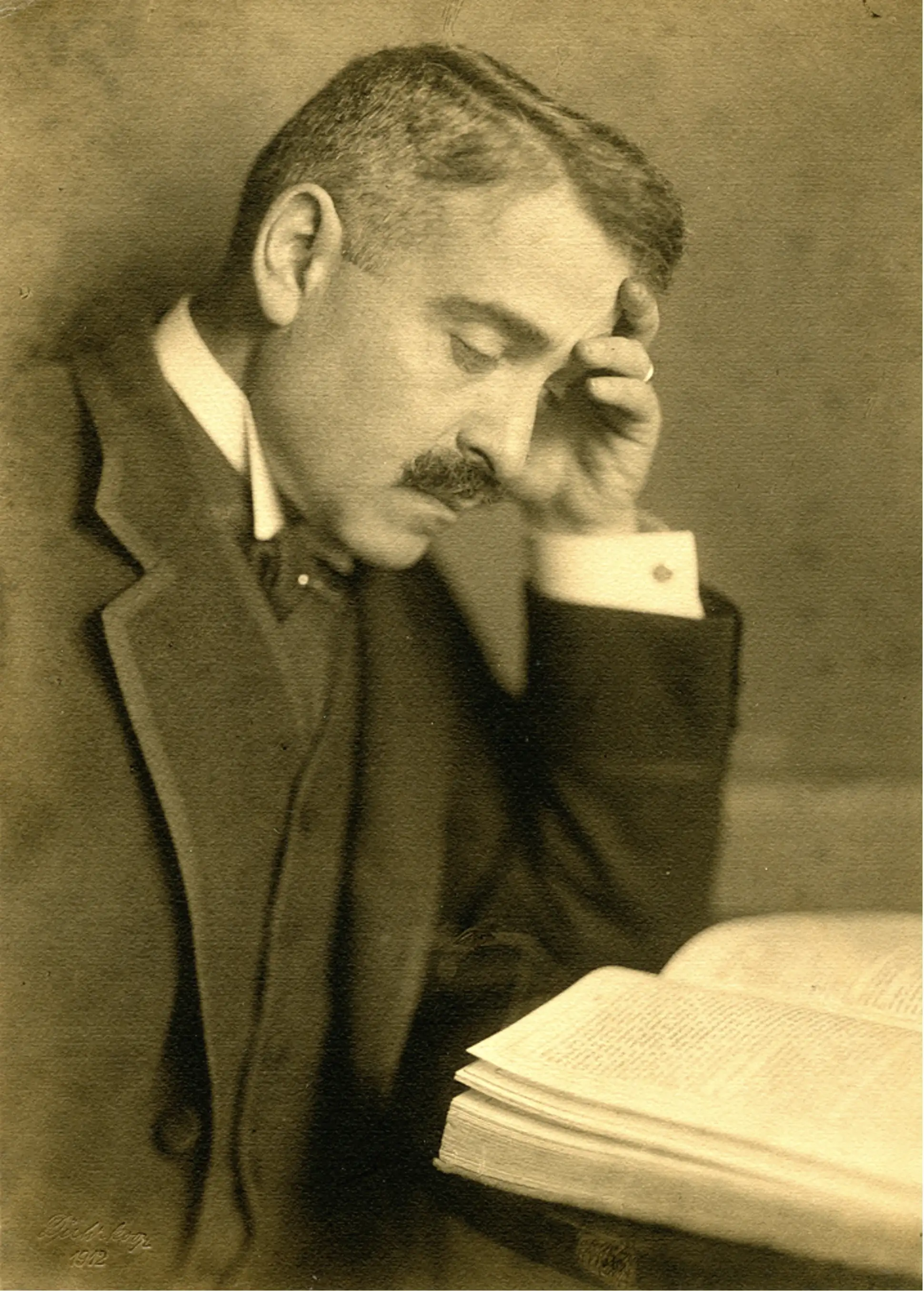

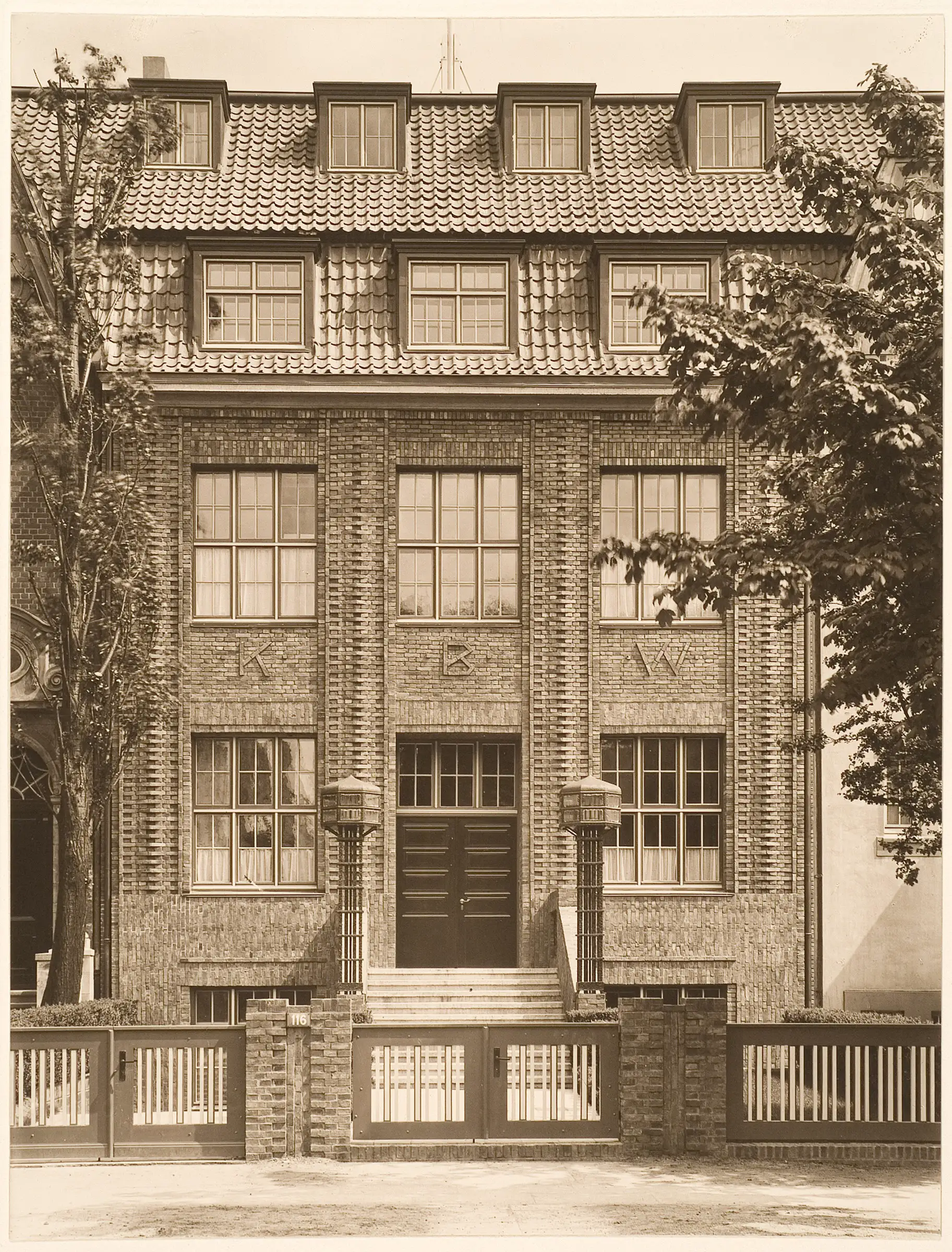

Portrait of Aby Warburg (1912) (1); Kulturwissenschaftliche Bibliothek Warburg, Hamburg (2). Photos courtesy Warburg Institute

The undertaking began with intensive immersion in the world of Warburg. “We visited archives, studied his Hamburg house, inhaled the smell of paper in the book stacks,” says architect Elizabeth Flower, an associate at Haworth Tompkins. “Our job has been to listen, absorb, and filter that history into this project.” Working largely with models, the firm reconceived the building to provide more room for books and students; it has been opened it up to visitors in a way hitherto impossible, realizing the founder’s vision for the integration of research, debate, and display.

Reception area view. Photo © Hufton+Crow

The first significant move was to revamp a distinctly unwelcoming reception area, shifting a glazed security screen to allow free public access to the first floor. With white walls and a terrazzo floor, the foyer makes a calm introduction to the Institute, but even so there’s a hint of the tangential ferment of Warburg’s thinking. A Coade stone frieze of Greek muses has been relocated from an out-of-the-way spot to hang over the waiting area. Modeled on a sarcophagus that hung from the facade of a nearby Georgian house, it was itself damaged in the wartime bombing that made way for the Institute. In a juxtaposition that pleases Sherman, it is next to a relocated door marked ‘Mnemosyne,’ the Greek goddess of memory. “The mother reunited with her daughters,” he says.

The Kythera Gallery. Photo © Hufton+Crow

Beyond the door, a warren of poky offices has been stripped out to create the 1,615-square-foot Kythera Gallery, overlooking the street and putting the product of research on full public view. Suspended screens, inspired by a system developed by Warburg in Hamburg, allow his London institute to display its esoteric image collection in ever-changing pairings for the first time.

The oak-floored gallery provides a more graceful route to the reading room, one of the Warburg’s most treasured spaces. Here, Haworth Tompkins has been careful to keep its interventions discreet while upgrading everything from windows to the security gate. “This is not a protected building, but we’ve treated it as though it is,” says Flower. Wooden bookcases designed by Holden were retained, and new joinery rhymes with the fluting of columns clad in tropical hardwood. Accumulated clutter was excised, in a process Haworth Tompkins calls “de-silting.” A deft balance has been struck, respecting the building’s spare aesthetic but also highlighting a richness that was overlooked when it opened—to bad reviews—in 1958. “They’ve uncovered more of Holden’s classicism than we knew was here,” says Sherman. These first-floor spaces wrap around the architects’ most dramatic intervention: a 140-seat lecture theater in an extension built out into the compact courtyard, separated from the original structure by glass-roofed lightwells on either side.

The Wohl Reading Room. Photo © Hufton+Crow

Though modest in size, it is rich in material character and symbolic detail. Walls and floor are lined in dark-hued woods. On the ceiling, an ellipse traced in structural poured-in-place concrete refers to the lecture hall of the original Institute. Ellipses were important to Warburg, who saw them as symbols that could somehow reconcile scientific and mythological conceptions of cosmic order. Other details also call back to Central European origins. In one corner stands a piano brought to London in the 1930s by the emigrée Viennese art historian Ernst Gombrich. On the facade, too, gray hit-and-miss brickwork echoes the Institute’s former library in Hamburg.

1

2

Facade detail (2); Edmund de Waal, library of exile, 2020 (2). Photos © Hufton+Crow

Warburg always envisaged an institution where debate and display would take place alongside study, and two-thirds of the building is still occupied by 360,000 books. Haworth Tompkins revived his unique classification system, with one floor given to each of four topics: Image, Word, Orientation, and Action. Rare volumes on subjects as diverse as astrology and astronomy, magic and migration appear on shelves in idiosyncratic, interdisciplinary order based on his “good neighbor” principle, says Sherman: “The book you need is always next to the one you are looking for.”

The entire collection remained on the premises throughout the renovation. Having learned a lesson from its remodel of the London Library, Haworth Tompkins planned the phased construction around the logistics of moving the stock: “The Tetris game of moving books, doing work and putting them back,” as architect Nigel Hetherington puts it.

The library at the Warburg Institute, London. Photo © Hufton+Crow

A few simple, sensitive moves have much improved the space for scholars. Book stacks were rotated 90 degrees, back to their original orientation, so daylight once again streams down the aisles; UV film to over windows on three sides protects the collection. There are more secluded nooks for quiet study. “Readers really enjoy them,” says Hetherington. “They are quite territorial.” There has been a lot of tidying up, but the library retains a strong hint of post-war austerity. Carpet has been swapped for an oxblood-red linoleum close in color to the one Holden originally used. Power cables are surface-mounted in utilitarian galvanized metal conduit. “It was nerve-wracking when readers returned,” says Hetherington, “but they all said it still feels like Warburg.”

Academics have also gained an important additional space from the renovation: the Wohl Reading Room tucked away in the undercroft of the lecture theater, one level below the street. It adjoins the relocated photographic archive, stored in a mix of modern roller-racking and timeworn filing cabinets. “The mismatched furniture is part of its character,” says Flower.

3

4

Views looking up through courtyard lightwells (4) and of the Hinrich Reemtsma Auditorium (4). Photos © Hufton+Crow

There’s an enjoyable interplay between old and new in the architecture, too. Raw concrete columns recall industrial structures by Charles Holden—perhaps best known for many London subway stations—and frame layered views out to the courtyard and through the building. At the edges one looks up through the glass-roofed, white-tiled lightwells and internal windows into first-floor rooms, glimpsing the Coade stone frieze and Holden’s fluted columns. It is a palimpsest of a sort that would surely have appealed to Aby Warburg. Following a project embodying his conviction that the past always shapes the present, his Institute and its extraordinary collections finally have both the secure home and the profile they deserve.