A photo by Robert Doisneau of cellist Maurice Baquet performing on a mountaintop in Chamonix, France, was the inspiration for the Geode, the newest outdoor performance space at Tippet Rise, the visual arts and music center on a working sheep and cattle ranch in Fishtail, Montana. There is no building in the 1957 image, just the musician with his instrument surrounded by the drama of nature, says Peter Halstead, who with his wife Cathy Halstead, is founder of Tippet Rise through the couple’s Sidney E. Frank Foundation.

Located roughly between Billings and Bozeman, Tippet Rise, opened in 2016, has a number of other performance venues, both indoors and out, but the Geode is its most intimate (intended for an audience of up to 40 people), and its most remote, sited on a ridge a ten-minute van trip on gravel roads or a five-mile hike or mountain-bike ride on trails from the heart of the art center’s 12,500-acre campus (for context, Manhattan is about 14,500 acres).

The Geode’s interior layer of Douglas fir cladding has been treated using yakisugi, a traditional Japanese technique. Photo by James Florio © 2024 Tippet Rise Art Center

Designed by the engineering firm Arup, who has been involved in many of the buildings and installations at Tippet Rise, the Geode is an assemblage of four triangular pyramids—one for the performers and three for the audience members—providing protection from the sun and the wind, but permeable to its environs. The elemental shelter seems well-suited to its surroundings and the nearly treeless, undulating terrain in the shadow of the Beartooth Mountains—a primordial landscape that Cathy describes as “raw” and “a bit terrifying,” where “everything is bigger than you ever expect it to be.”

The brief called for a venue that could accommodate a range of performances, from solo musicians to octets. But above all, the Halsteads desired that the Geode would work without amplification. So, with the help of parametric modeling tools, and its SoundLab simulation space, Arup manipulated the geometry and materials to optimally direct sound and its reverberations. The four structures, the tallest of which is 18 feet high, have frames of weathering steel, touching the ground at a total of 26 points. On each pyramid, one face has been left open, with the other two clad in two layers of Douglas fir boards. While the outer layer is left unfinished so that it patinas over time with exposure to the elements, the inner one has been charred using the traditional Japanese yakisugi technique, enhancing its resistance to pests, fungi, and to fire (a particular concern in the often-parched landscape). As part of the treatment process, the inner boards have been scraped with a wire brush, creating subtle grooves in the wood surface. The texture helps scatter higher frequency sound waves, mellowing and “taking the edge off,” explains Raj Patel, Arup’s project director and global leader of the firm’s acoustics, audiovisual, and theater consulting practice.

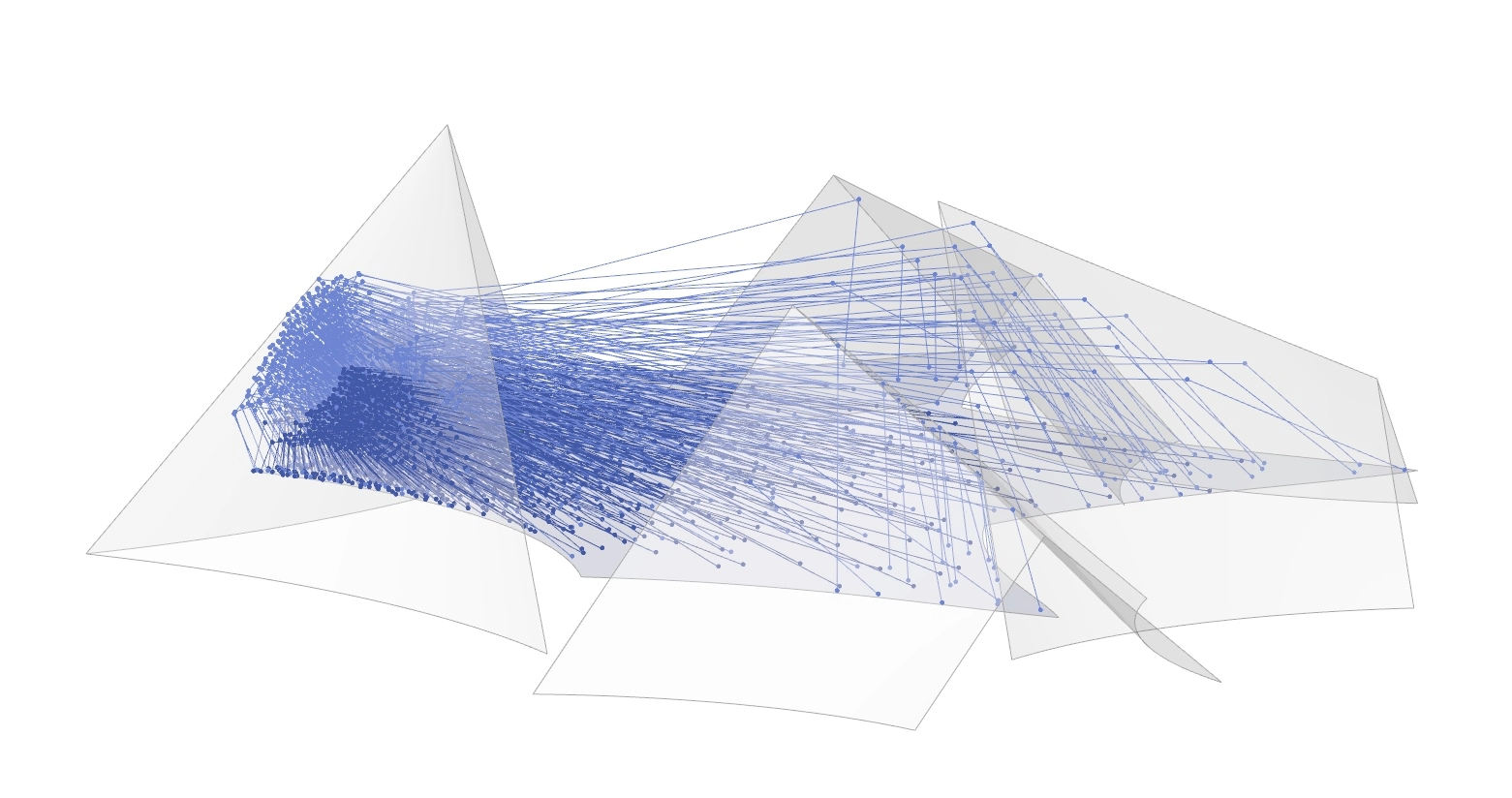

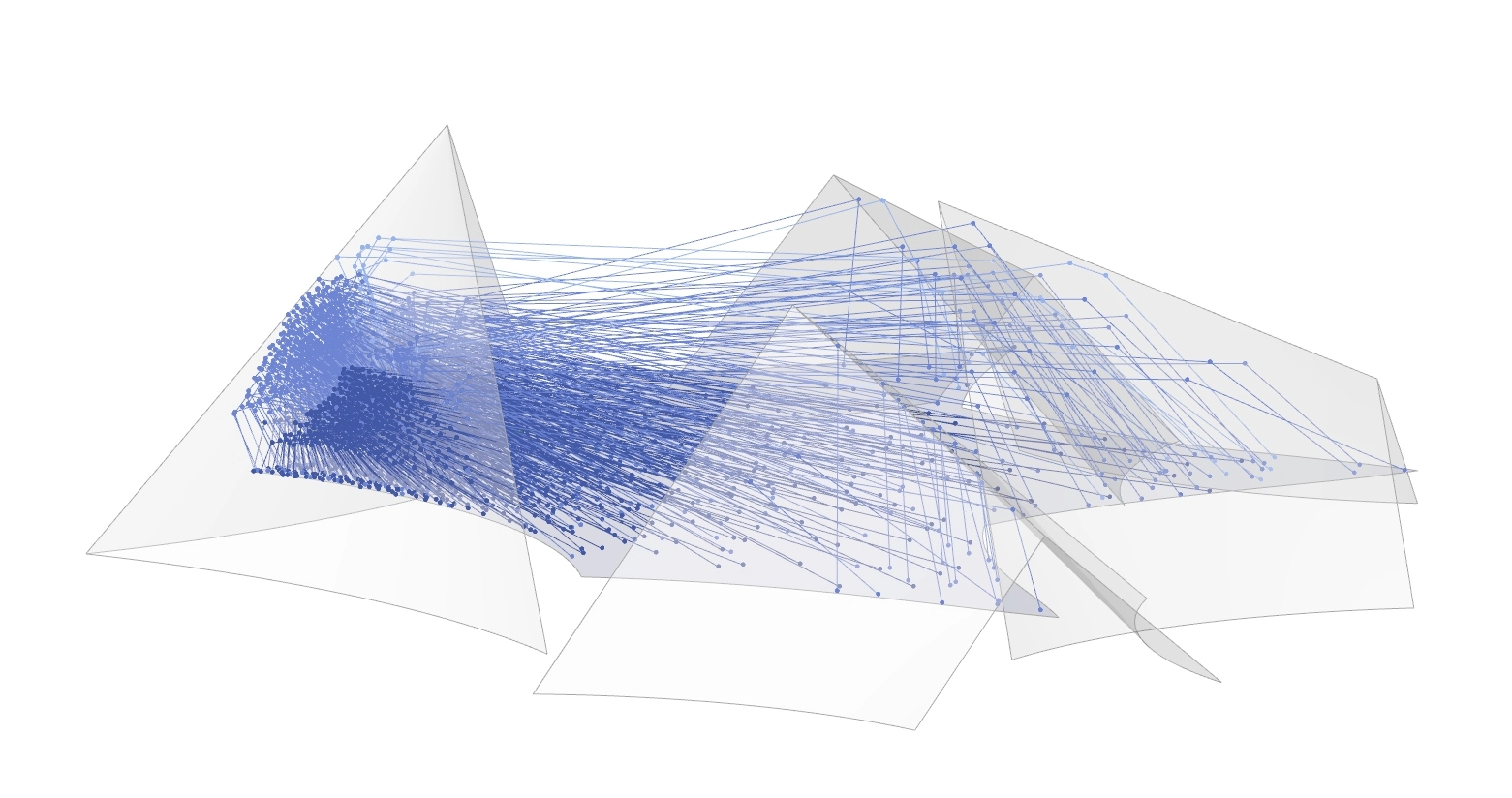

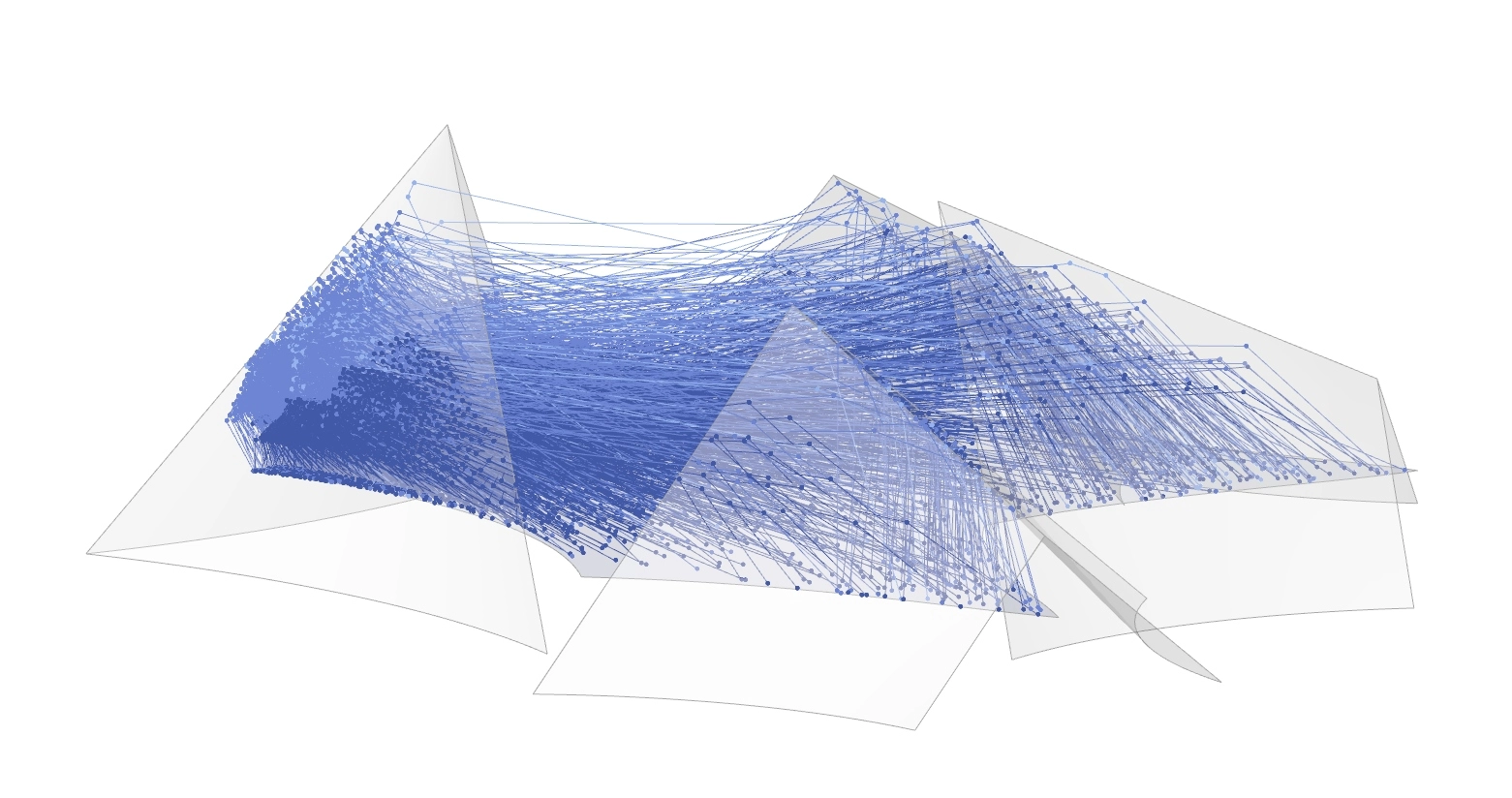

Diagrams showing the sound reflection sequence within the Geode. Images © Arup

The scheme accounts for the path of the sun, with the structures oriented so that the performers’ shelter is to the north, and the three others to the south, creating shade for the musicians and the audience throughout the summer season during the hours that concerts are expected to take place—from the early morning to the late afternoon. While providing shelter from the wind, the Geode’s cladding is lifted off the earth, decreasing lateral loads on the structures, allowing them to be less hefty than they would have been otherwise. In addition, the approach meant that the Geode could be tied to the ground with a series of micropiles rather than a continuous foundation. This “light touch” thinking extends to the Geode’s overall siting strategy, with its location selected to avoid extensive excavation or construction of new roads, despite its distance from the main part of campus.

Cellist Arlen Hlusko performs at the Geode in August. Photo by Kevin Kinzley © 2024 Tippet Rise Art Center

Fittingly, given the photo that served as inspiration, the inaugural concert was a cellist. On August 17th, Grammy-winning musician Arlen Hlusko performed a varied program that included Bach as well as new works. Specifically commissioned for the event was Àkweks Katyes (The Eagle Flies), by composer Dawn Avery, who is of Mohawk descent. As intended, the sound within the Geode was clear, rich, and enveloping.

Hlusko’s performance is part of an annual Tippet Rise music festival that this year extends over five weekends, from August 16 to September 15, encompassing classical and contemporary chamber concerts, performed by artists invited from all over the world. But beyond music, Tippet Rise is known for its large-scale sculpture, with works by Mark di Suvero, Alexander Calder, Ai Weiwei, among others. The property is home to several site-specific pieces, some by architects, such as the three monumental concrete structures by Madrid- and Boston-based Ensamble Studio, whose poured-in-place forms were literally shaped by the earth on which they sit. Sited not far from the main indoor performance space, the Olivier Music Barn, is a pavilion by Pritzker Prize-winner Francis Kéré with a roof of bundled ponderosa and lodgepole pine logs.

1

2

Wendy Red Star, The Soil You See…, 2023 (1); Richard Serra, Crossroads II, 1990 (2). Photos by James Florio, © 2024 Tippet Rise Art Center (`1), by permission, © 2024 Richard Serra / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Earlier this year, the Halsteads added two newly acquired pieces to the Tippet Rise landscape: a 1990 work by Richard Serra of eight-inch-thick steel plates arranged at 90-degree angles, and The Soil You See…, a sculpture by Wendy Red Star, a Native American raised on the nearby Apsáalooke reservation. The piece, which grapples with the legacy of U.S. treaties with Indigenous tribes, was recently displayed on the National Mall.

The Halsteads continue to contemplate other new works. About a year ago, they acquired Fifth Season, an immersive piece by Sara Sze first shown at Storm King, in Orange County, New York. At more than 50 feet long and comprising painted surfaces, photos, and projections, it is intended for an indoor environment, and therefore requires some sort of shelter in which to house it. The couple and Sze are now discussing how and where it will be displayed. “We are just at the beginning of that conversation,” says Cathy. With luck, visitors will soon be able to enjoy not only Sze’s piece, but also a new intervention in the vast landscape.