In Focus

Paris Prepares for the 2024 Summer Olympics With a Strategic Mix of New Construction and Renovation

Paris

The ads first appeared in the Métro in late January this year. Above a woman working at a laptop on a desk shared with her cat, a giant caption read, “To save time during the games, remote working is important.” Why, you might wonder, was an event billed as a moment of joy and excitement for the city, not to mention a source of pride and prestige for the nation—the Paris 2024 Summer Olympics, no less—being presented as the sort of calamity that would shut people up at home as in the dark days of the Covid lockdown?

The fear of public-transport overcrowding stems from the fact that the Paris Games will be the least architectural—in terms of new construction—in decades. When making its 2015–16 Olympic bid, the French delegation boasted that the city already had most of what was needed, and what it didn’t have was already programmed. The now mythic 80,698-seat Stade de France in Saint-Denis (Constantini, Macary, Regembal, and Zublena, 1995–98) would do just fine for the athletic competitions, Paris was not lacking in other Olympic-class sports facilities, and the government had already rubber-stamped major new Métro extensions that were scheduled to complete in time to ferry the estimated 15.3 million Olympic and Paralympic visitors around town. Even the Olympic Village was arguably already on the books, since developers had been eyeing that sector of the suburbs, between Saint-Ouen and Saint-Denis, for years—indeed, property and construction giant Vinci had acquired a chunk of the land in 2011, long before the bid.

After the Games, the Olympic Village, master-planned by Dominique Perrault, will house almost 6,000 Parisians. Photo © Elise Robaglia, click to enlarge.

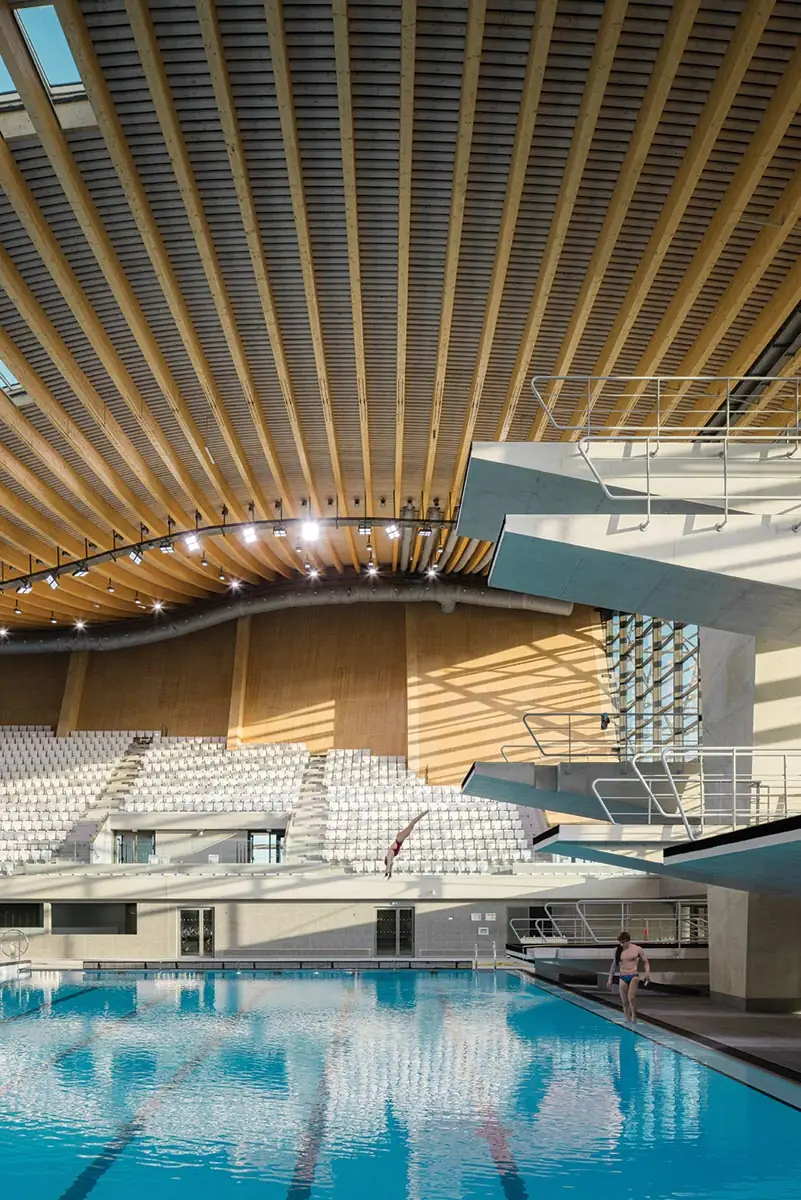

The Aquatics Center seats 5000 spectators. Photo © Simon Guesdon

Consequently, just two new purpose-built structures would be needed for the games: what has now been baptized the Adidas Arena, on the city’s northern edge, where the badminton and rhythmic-gymnastics competitions will be held; and the Aquatics Center, in the shadow of the Stade de France, where diving, synchronized-swimming, and water-polo contests will take place. Avoiding the waste issues that have dogged the aftermath of Olympiads in other host cities (notably Athens and Rio), the Paris games would represent, according to the bid submission, “a model of environmental excellence in line with the historic Paris Agreement on climate.”

The Adidas Arena designed by Scau and NP2F includes multiple gymnasiums. Photo © Guillaume Bontemps / Ville de Paris

As a result, unlike almost all other host cities in recent memory, which concentrated their venues in one sector of town, Paris will disperse its games across 25 sites within an 18-mile radius of the Olympic Village—except for the sailing competitions, programmed 410 miles away in Marseille. The success of this third Paris Olympiad, exactly a century after the last one, hinges on people-moving.

Unsurprisingly, things have not quite gone according to plan where the Métro extensions are concerned, with Covid and cost overruns having caused major delays. Almost none of the proposed new lines will be complete before the Games, and the race is on to finish the one key segment in time, namely, the extension of Line 14 at either end, so that it will link Orly Airport on the city’s southern outskirts to Kengo Kuma’s new Saint-Denis–Pleyel station in the northern suburbs, next to the Olympic Village. Even for these relatively short sections (nine miles out of a total of 124), the logistical problems have been enormous: the suspension of tunneling for a whole year due to unforeseen leaks; Métro-car-supplier Alstom’s tardiness in delivering all the new rolling stock needed for the line to run at peak performance; and the devising and testing of an entirely new software system to operate the driverless trains at greater frequency along more than double the length of track, which requires closing the line for days on end.

The new Kengo Kuma–designed Saint-Denis–Pleyel Metro station serves the Olympic Village. Photo © Société des Grands Projets / Gérard Rolando

Where the new buildings are concerned, timing at least has been respected, even if some of the ambitions have fallen by the wayside. In response to the tough surroundings in which the $150 million, 8,000-seat Adidas Arena is sited, right next to a major freeway interchange, architects Scau and NP2F built a hulking concrete monolith that, in a drive for economy, has zero pretensions to Olympic iconicity. Once the Paralympics are over, this ascetic aluminum-clad games machine will become home to the ambitious American-owned Paris Basketball club. Despite the low-carbon claims made by its architects—including recycled plastic for the seats and low-emissions concrete—the complex, which also contains leisure facilities for the local community, seems a traditionally resource-heavy response to this type of brief.

Over at the Plaine Saint-Denis, on the other hand, the Franco-Dutch team of Ateliers 2/3/4/ and VenhoevenCS turned to timber in an attempt to align their $189 million, 5,000-seat Aquatics Center with the goals of the Paris Agreement. Suspended from a massive wood frame, the 295-foot-span wave-form CLT roof—which, in contrast to the gloomy sobriety at the Arena, yells “Olympic icon” when seen from inside—is not only bio-sourced but also reduces the internal volume that must be cooled or heated, while outside it carries 54,000 square feet of photovoltaic panels that, the architects say, constitute the largest urban solar-energy farm in France. Connected to the Stade de France by a new footbridge crossing the A1 freeway, the Aquatics Center will be used by local clubs as well as by the French Swimming Federation once the games are over. Although its interior, which commands striking views of the stadium, will ensure all the televisual spectacle required for a global event of this magnitude, the exterior falls sadly short of icon-hood (however hard it tries), no doubt due to the 20 percent budget cut the architects were asked to implement in a specially organized third round of the design competition.

Meanwhile, a little farther to the northwest, on the banks of the Seine, the 126-acre Olympic Village also makes timber its environmental leitmotif. Master-planned by Dominique Perrault, the development hasn’t turned out to be quite the national forest fest its champions initially trumpeted, since fire regulations forbade building above 92 feet with a wood frame, and the French timber industry, long eclipsed by concrete, is not yet up to speed with regard to supply. Nonetheless, a respectable 45 percent of the wood used came from France, and, according to the organizers, embodied carbon is 30 percent lower than in a classic development of this type. Moreover, the buildings are intended to function without conventional air-conditioning in extreme-heat episodes, as predicted for the year 2050—insulation, natural ventilation, and geothermally supplied under-floor cooling will, their builders say, keep them comfortable. Planned first and foremost as a new urban neighborhood—conversion from Olympian to civilian accommodation will begin in September—the village has transformed a rundown area of light industry and small businesses into a pleasant if banal residential and office district. The future home of around 6,000 people, this 3.5 million-square-foot gentrification operation—30 percent social housing and 70 percent private—was realized in just six years, turbocharged by the games.

The French delegation’s decision to commission as few new buildings as possible does not mean the country’s construction industry has remained entirely idle, since reusing existing structures often required bringing them up to standard. One example is the Yves-du-Manoir stadium in Colombes—the principal site of the 1924 Olympics—which Celnikier Grabli Architectes has remodeled for the 2024 hockey contests. Another is the Georges Vallerey swimming pool in Paris’s 20th arrondissement, also a relic of the 1924 Olympiad, for which AIA Life Designers has constructed a new retractable roof.

1

2

The Yves-du-Manoir stadium (1 & 2) was renovated by Celnikier Grabli Architectes to host hockey. Photos © Simon Guesdon

AIA Life Designers gave Georges Vallerey pool a retractable roof. Photo © Hugo Hébrard

Meanwhile, at the Île des Vannes up near the Olympic Village, Chatillon Architectes has brought the 1971 Grande Nef Lucien-Belloni back from dereliction as a training space for the rhythmic-gymnastics teams. Commissioned by what was then a Communist municipality, this extraordinary technical feat—two prestressed-concrete arches maintained in place by a parabolic steel grid that forms the roof—was designed by architects Pierre Chazanoff and Anatole Kopp in collaboration with the engineer René Sarger. A symbol of postwar optimism, it has been reworked to consume less energy and will be returned to the local community in what is still an underprivileged neighborhood.

Renovated by Chatillon Architectes, the Grande Nef Lucien-Belloni is now a gymnastics training space. Photo © Antoine Mercusot

Also being led by Chatillon, the renovation of the Grand Palais (programmed long before the city made its Olympic bid) has been partially speeded up so that its celebrated Art Nouveau stairway will serve as the backdrop to the fencing and tae kwon do competitions. In this way, a link will be made with the very first Paris Olympiad, held in 1900 as part of that year’s Exposition Universelle. Located on a prominent site between the Seine and the Champs-Élysées, the Grand Palais is one of two buildings that survive from the fair.

The Chatillonrenovated Grand Palais (opposite), will host fencing and tae kwon do competitions. Photo © Laurent Kronental

As the example of the Grand Palais goes to show, the architectural sobriety championed in the French Olympic bid was partly possible because the icon that is Paris itself obviated the need to build new ones. Indeed, to underscore the importance of the Paris brand, the Olympic opening ceremony will take place in the heart of the city rather than in the Stade de France. The first time a host country has attempted such an exploit for the summer Games, the event will be attended by 300,000 people—almost four times the stadium’s capacity.

Organizing such a huge public spectacle on three-and-a-half miles of the River Seine is not without its logistical headaches. Among the Herculean security implications is the question of the bouquinistes, the secondhand-book-sellers, who were ordered to remove their famous quayside stalls at their own expense. Mindful of the bookstalls’ fragility and fearful that they might not be allowed back after the ceremony, the bouquinistes protested, causing such a ruckus that President Macron stepped in to say they could remain. His decision is among the reasons the ceremony’s capacity has been reduced by half, from the 600,000 spectators initially planned. Meanwhile, the Fédération nationale de l’immobilier—the National Real Estate Federation—made headlines when it warned that the balconies of buildings lining the Seine, many of them over 150 years old, might not resist the weight of too many people crowding onto them to watch the show.

Should landlords need to carry out repairs, they’ll have to hurry: no scaffolding may go up during the Games, presumably due to security concerns, but also with Paris’s image in mind. Likewise, the evacuation of squatters and the removal of rough-sleeping migrants has accelerated these past few months: the interior ministry pleads security issues, while NGOs denounce a form of “social cleansing.” After Macron publicly admitted that there was not only a plan B but also a plan C in case of too great a terrorist threat, many are wondering whether the July 26 ceremony will go ahead as planned. Bets are also on as to whether Paris mayor Anne Hidalgo will keep her promise to jump into the Seine—for health reasons, swimming in the river has been banned since 1923—following the city’s $1.5 billion cleanup to allow the triathlon and open-water contests to use it. If the river has been made genuinely safe, this will be a truly Olympian legacy for Paris, whose official motto, lest we forget, is fluctuat nec mergitur—“though tossed about, she does not sink.”