Double Vision: Studio Gang Takes on Renovations and Expansions at Two American Museums

New York / Little Rock, Arkansas

Architects & Firms

At first blush, the challenges were remarkably similar: design a major addition to a sprawling museum that had grown piecemeal over many decades, creating a new face for an old institution and cleaning up a host of nagging problems in the process; integrate architecture and landscape at an urban project set within an existing park; respect the historic fabric, but inject a big dose of bold design to energize the client’s mission. But New York isn’t Little Rock, and the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) isn’t the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts (AMFA). So Studio Gang developed schemes for the two projects that have strikingly different expressions. Though both might be described as “organic” in form, the one in New York draws its shape from geology, and the one in Little Rock conjures images of plants and flowers.

1

New entrances draw visitors to the Museum of Natural History (1 & 2) and the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts (3 & top of page). Photos © Alvaro Keding/AMNH (1), Iwan Baan (2 & 3), click to enlarge.

2

3

The key to each project was figuring out how to break through the thick carapace that had developed over the years separating the museum from its surroundings. Each commission required Jeanne Gang and her team to subtract, then add, removing pieces that got in the way of the museum’s reaching out to its neighbors and then inserting an alluring new threshold.

At AMNH, time is the force driving everything. From its jaw-dropping dinosaur skeletons and multimillion-year-old fossils to its displays on evolution, the museum on Manhattan’s Upper West Side reveals the wonders of our planet and the universe through the lens of time. Studio Gang’s design for the new Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation expresses that same hidden force, evoking the form of an ancient canyon sculpted by wind and water over the course of many, many years. First announced in 2014, the 230,000-square-foot, $465 million Gilder Center serves as a new gateway on the west side of the 149-year-old original building. What had once been a tucked-away back entry off Columbus Avenue and a quirky piece of Theodore Roosevelt Park has been transformed by Jeanne Gang and her team into an immediately recognizable feature attraction.

4

5

The canyon-like atrium (4 - 6) was formed by spraying shotcrete on a network of rebar and then hand-finishing it, creating a self-supporting structure with a crafted texture. Photos © Iwan Baan

6

With its bulging facade clad in 18-by-9-foot panels of angled strips of Milford pink granite and punctuated by a five-story glazed wall and curvaceous windows, the Gilder sets itself apart from the existing dark stone-and-brick buildings to which it is attached. But it plays nice with its older neighbors, matching the height of the Neo-Romanesque building to its south and aligning its floors with those of that structure too. Its masonry courses recall the layers of Manhattan schist on which it sits. And its pink granite comes from the same source as the stone on AMNH’s grand entrance on Central Park West, on the opposite side of the four-block campus—a material echo that will resonate with visitors of all ages who have made many trips to the institution.

As soon as you step into the Gilder Center, you’re pulled into a five-story high, 10,000-square-foot atrium topped by a set of large oval skylights. There are no right angles here. Instead, you’re enveloped by a self-supporting cavelike structure made of shotcrete blasted onto an undulating network of rebar without the use of disposable formwork. (Shotcrete was invented by Carl Akeley, founder of the AMNH Exhibitions Lab.) Gang toured train tunnels under construction to see how shotcrete has been used in large projects, but the Gilder atrium has more organic curves, which generate a wide-eyed wonder in most visitors. “I’ve always been fascinated by spaces of adventure, like canyons and gorges,” says Gang. Such places encourage flow and movement, which are important in what is essentially a giant entry lobby. “We’re constantly investigating structures in nature,” says Weston Walker, a design principal at Studio Gang and the partner in charge of the firm’s New York office. The architects also looked at Eero Saarinen’s models of the TWA Terminal at JFK Airport and Antoni Gaudí’s models of La Sagrada Familia in Barcelona, curious about how forms can merge and connect.

The role of a natural history museum in our society has never been more important, says Ellen V. Futter, who stepped down as AMNH president in April after nearly 30 years in that role. Researching, collecting, and exhibiting science are essential tasks in the wake of Covid and “in a post-truth era,” she states. Gang’s design “invites references to the natural world and inspires curiosity,” says Sean M. Decatur, the institution’s new president. “It’s a place where people will want to wander around and explore.”

Though fluid in form, the Gilder Center reinforces the axial arrangement of the museum’s original plan prepared in 1872 by Calvert Vaux and J. Wrey Mould, and aligns its atrium with the grand entry hall on the opposite side of the campus. Knitting together 15 decades of growth was a key challenge. The west sector of the museum, in particular, was notorious for its U-shaped circulation and dead ends that charmed regular visitors but maddened everyone else. Gang’s addition connects to nine other buildings at 33 different points, establishing an uninterrupted flow throughout the campus. Making her building porous to the rest of the museum and to the city was important, says Gang. Now visitors in the Gilder atrium can look out toward 79th Street and, on clear days, see the sun set past the Hudson River.

Anchoring the center of the Gilder atrium, a grand stair takes you up two floors and provides stepped seating on one side, so you can relax or listen to a presentation on the ground level. On the south side of the space, glass cases with 4,000 items from the museum’s collection rise three stories in a gesture reminiscent of Gordon Bunshaft’s glass book tower inside the Beinecke Rare Book Library at Yale, and one that expresses Gang’s goal of using architecture to reveal the museum’s mission. On the north side of the ground floor, visitors discover an insectarium with displays of live ants and insects, as well as a giant model of a beehive. On the floor above, a vivarium allows museumgoers to walk among fluttering butterflies and learn about these fascinating creatures. An immersive and interactive experience called Invisible Worlds surrounds visitors on the third floor with moving images of oceans, skies, the microscopic, and the galactic. On the fourth floor, a reading room with a mushroom-shaped column at its center offers an elegant place to relax and enjoy views of Theodore Roosevelt Park. Ralph Appelbaum Associates designed all the exhibits in the new building.

A reading room on the fourth floor serves as the public face of the museum’s library and learning center. Photo © Iwan Baan

When plans for Gilder were first announced in 2014, some residents of the Upper West Side protested changes to the park and the loss of some trees. Making an omelet requires breaking some eggs. In this case, that meant tearing down some unglamorous structures and redesigning outdoor spaces along Columbus Avenue. Reed Hilderbrand, the landscape architects for the project, have created a gracious entry sequence, with paths, benches, and native species, and an expanded lawn on the north side of the block, and 23 new canopy and understory trees.

Click plans to enlarge

Click section to enlarge

From New York to Little Rock

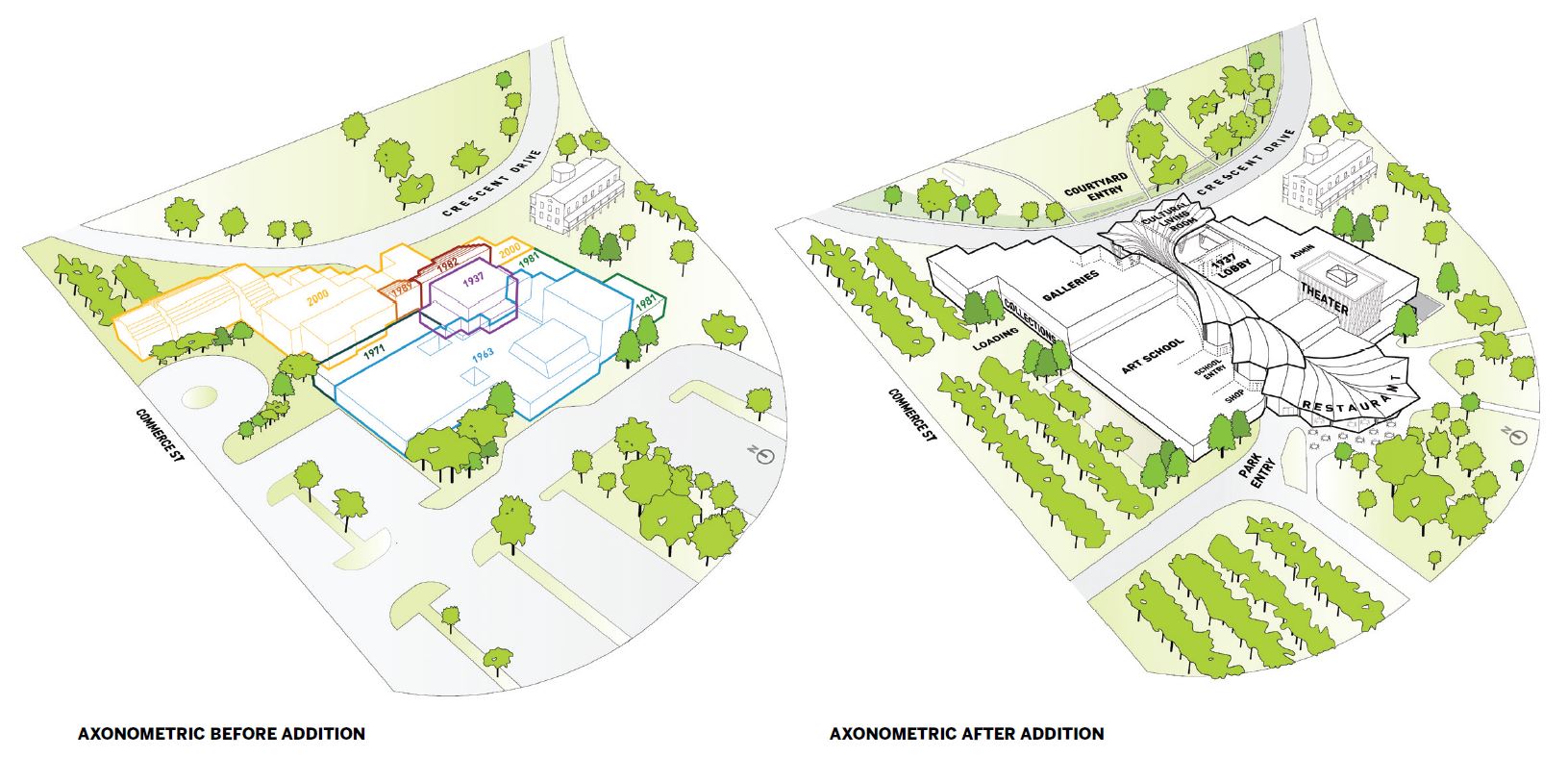

At the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts, Gang tackled a building that had grown over the course of 80 years to include eight additions and a multitude of styles. It had become an architectural jigsaw puzzle—hard for visitors to navigate and disconnected from its setting in Little Rock’s MacArthur Park. The challenge here was to add yet another piece to this beloved institution while making sense of it all, and reaching out to its leafy surroundings and the city beyond. Eventually, Gang decided that the right approach was to crack open the structure and graft a sinuous, light-filled atrium onto it.

A new entry on the south side reaches out to MacArthur Park with a roof canopy that extends as much as 40 feet, to shade the building and outdoor diners. Photo © Iwan Baan

A curving atrium provides access to all major spaces at the Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts. Photo © Iwan Baan

The organically shaped insertion, which Gang calls the Blossom, provides a dramatic counterpoint to the existing museum’s orthogonal architecture. It runs from the front on the north, ripples through the torso of the building, and then fans out like a giant gingko leaf as it emerges on the south to face MacArthur Park. A curving concrete structure topped by a pleated roof, the Blossom negotiates the sloping terrain, stepping down 6 feet from north to south. To reconnect the museum to the city and Crescent Drive on the north, the design team—including Little Rock–based Polk Stanley Wilcox Architects—removed a set of additions built in the 1980s and early 2000s, revealing the 1937 Art Deco front facade and returning it to its role as the main entrance.

Welcoming visitors now is a glass-fronted pavilion raised one story above an entry courtyard paved with a honey-color granite that complements the white oak–clad roof soffit of the new building. The pavilion houses what the museum calls the Cultural Living Room, a 5,960-square-foot space furnished with sofas, comfortable chairs, tables, and a bar that serves coffee in the morning and cocktails in the evening. It’s a casual space flowing directly to the galleries on the same floor and then down to the atrium, which provides access to the Windgate Art School plus a 350-seat performing arts theater, a 153-seat lecture hall, a museum store, and a restaurant with both indoor seating and a covered outdoor terrace looking onto MacArthur Park. Clerestory windows under the central spine’s snaking roof bring daylight into the heart of the building and make navigating the museum clear and intuitive. Individually suspended from the roof are more than 6,000 plywood strips that diffuse light and sound, and add to the dynamic quality of the spine.

7

The Cultural Living Room (7) acts as a social hub, with views to the restored 1937 facade (8). Photos © Iwan Baan

8

“We needed to provide the connective tissue for the museum,” says Gang of the new spine and flowing spaces. Sustainability was an important strategy driving the 133,000-square-foot project, so the architects kept as much of the old building as possible, refurbishing spaces like the theater, lecture hall, and art school, and adding new galleries on top of what had been galleries, a restaurant, and a variety of support areas. “We edited and excavated old elements to create a new, more connected museum,” says Gang. Deep cantilevered eaves on the front and back of the Blossom protect the outdoor spaces underneath and the ones inside from the full impact of the sun, while a radiant-heating and -cooling system in the concrete floor slabs reduces energy use. Juliane Wolf, a design principal and partner at Studio Gang, likens the daylit spine to a crack in a sidewalk where plants emerge from the soil below.

On the main floor, the restaurant spills out to MacArthur Park. Photo © Jason Masters

Inheriting a hodgepodge of brick, stone, precast-concrete and metal structures ranging in color and texture, Gang unified them by painting them all with a common palette of hues that reads as a blue-gray white. Creating a new, cohesive identity for the museum was a top goal, but so was making key parts—such as the Cultural Living Room, the arts school, and restaurant—visible to the public. “Enhancing and clarifying the public experience was important,” says Wolf, especially since admission to the museum is free.

From the start of the project, Gang collaborated with Kate Orff and her New York–based landscape architecture firm SCAPE to address key siting and sustainability issues and to integrate indoors and out. On the north side of the site, Orff’s team designed Crescent Lawn to draw people to the main entrance, while on the south it created a series of outdoor spaces flowing from the museum’s dining terrace to its “Event Lawn,” and finally to paths and plantings blending seamlessly with the rest of MacArthur Park. Building and landscape work together—for example, on the south end, with “petal” gardens capturing rainwater from the museum’s roof and absorbing it into the soil.

The galleries occupy the northwest quadrant of the complex, offering 20,000 square feet of space for the museum’s collection of 14,000 objects ranging from 14th-century European paintings to works on paper, contemporary crafts, and pieces by living artists such as Oliver Lee Jackson and Ryan RedCorn. With their white oak floors and 15½-foot-high ceilings, the galleries are comfortable and understated. Two design moves add punch: an angled pathway slicing through the rectangular rooms and an “Art Perch” at one end that provides a deep seating ledge in front of a large window (the only source of daylight in the galleries).

7

The Art Perch displays an artwork by Natasha Bowdoin and offers views of the Crescent Lawn to the north. Photo © Iwan Baan

Gang and Orff carefully orchestrated a sequence of spatial experiences that draw you inside and through the museum. It starts with the angled glazing on the Cultural Living Room, reflecting images of the lawn behind you as you walk under the elevated pavilion toward the entry courtyard. A tall Henry Moore sculpture, Standing Figure: Knife Edge, anchors one corner of the outdoor space, but a dearth of landscaping here seems like a lost opportunity. The two-story lobby behind the 1937 facade is also underwhelming, with its dark walnut paneling reminiscent of a corporate boardroom. As soon as you step into the soaring atrium, though, you’re pulled into a thrilling space that flows down a grand staircase and out to MacArthur Park. If you turn around, you can take a different stair up to the galleries and the Cultural Living Room on the upper level. The spacious lounge is gracious and alluring, with views in three directions. If you look to the entry courtyard, you find yourself at eye level with the museum’s name carved into the Deco-era limestone wall now revealed. Gang says she loves this perspective because it reminds her of riding Chicago’s elevated trains and looking into nearby buildings as you move along.

Gang’s accomplishment at the natural history museum and the art museum was crafting a pair of 21st-century institutions that read as palimpsests, with layers of history emerging and syncing with the contemporary. The two projects deliver a bold message that change can be both dramatic and sensible, and that architecture can help make science and art exciting for people of all ages.

Click graphic to enlarge

Click plan to enlarge

Credits

Architect:

Studio Gang — Jeanne Gang, founding principal and partner; Weston Walker, design principal and partner; Ana Flor Ortiz, design principal; Anu Leinonen, design-management director; Anika Schwarzwald, project leader; Margaret Cavenagh, Maciej Kaczynski, Andrew McGee, Arthur Terry, Spencer Hayden, Kathleen Stranix, Stanley Schultz, John Castro, Jay Hoffman, Wei-Ju Lai, Bethany Mahre, Dimitra Gelagoti, Claire Cahan, Chris vant Hoff, Mark Schendel, Peter Zuroweste, Schuyler Smith, Franco Bolanos, William Lambeth, Elif Erez, Magda Wala, Gabrielle Poirier, Natalya Egon, Juan De La Mora, Paige Adams, project team

Architect of record:

Davis Brody Bond

Engineers:

Arup (structural, acoustics, AV); BuroHappold (electrical, mechanical, plumbing, fire protection, facades); Atelier Ten (sustainability); Langan (geotechnical, civil)

General Contractor:

AECOM Tishman Construction

Consultants:

Reed Hilderbrand (landscape); Ralph Appelbaum (exhibition); Renfro Design Group (lighting); Clinard Design Studio, AMNH Exhibition (exhibition lighting)

Client:

American Museum of Natural History

Size:

230,000 square feet (Gilder: 190,000 square; renovation: 40,000 square feet)

Cost:

$465 million

Completion Date:

May 2023

Sources

Shotcrete:

COST of Wisconsin

Concrete Superstructure:

Winco

Steel Superstructure:

Orange County Ironworks

Stone Megapanels:

Island Exterior Fabricators

Metal/Glass Facades and Skylights:

W&W Glass

Glazing:

Interpane

Cabinetwork:

Whalen Berez Group