Sekou Cooke on Hip-Hop as a Blueprint for Architecture

Photos by Michael Barletta, courtesy Sekou Cooke (left); by Gene Philips Photography (right)

-by-Olalekan-Jeyifous-2015.-Image-Courtesy-of-Olalekan-Jeyifous_result2.webp?t=1670019006&width=1080)

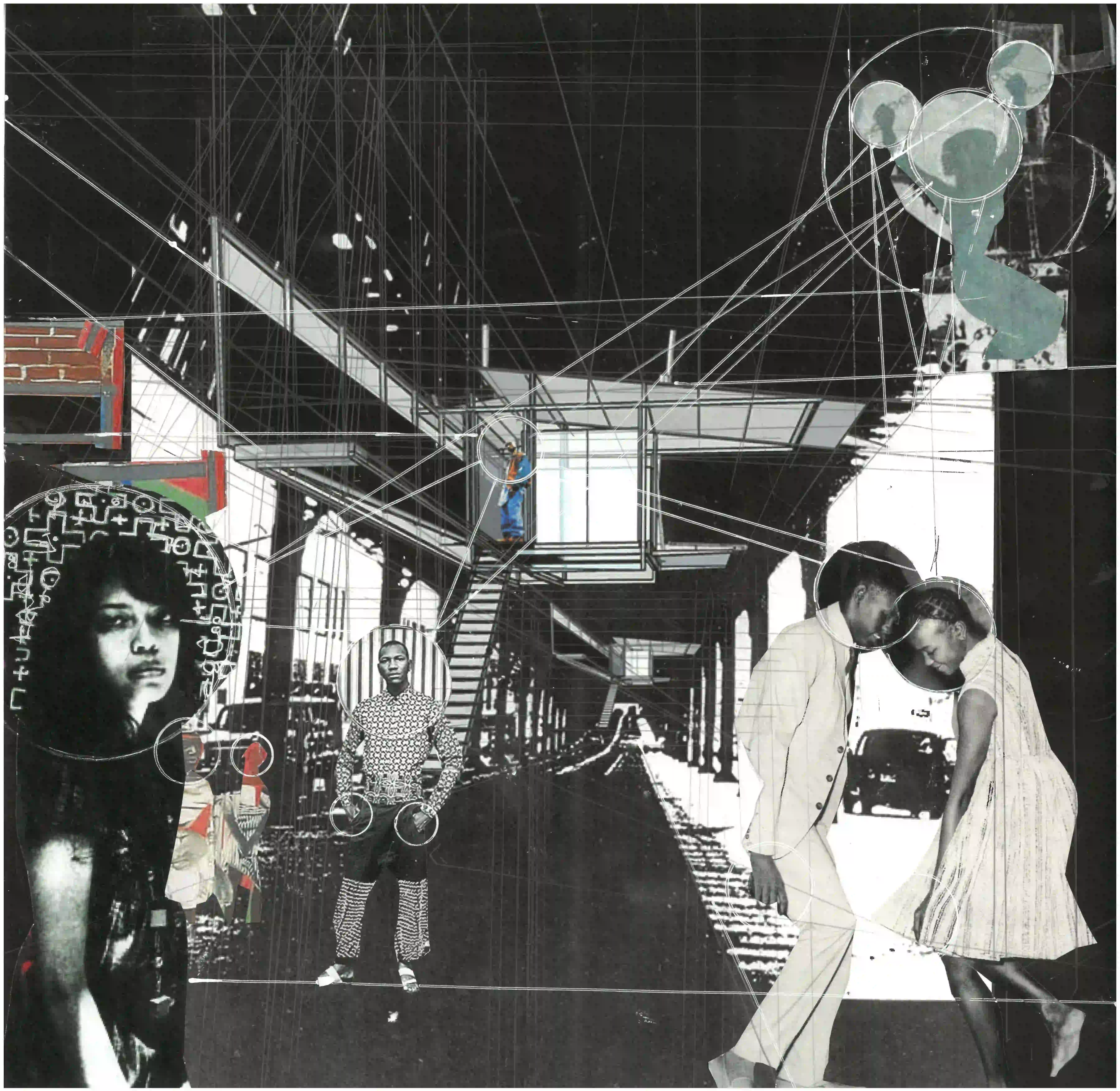

Shanty Megastructures Project (2015) by Olalekan Jeyifous. Image Courtesy of Olalekan Jeyifous

Photo by Gene Philips Photography

Exhibition view. Photo by Gene Philips Photography

-by-Olalekan-Jeyifous-2015.-Image-Courtesy-of-Olalekan-Jeyifous_result2.webp?t=1670019006&width=150)

Architect and writer Sekou Cooke is the curator of Close to the Edge: The Birth of Hip-Hop Architecture, an exhibition which opened in October at the Museum of Design Atlanta (MODA), after appearing at three other venues across the United States. The exhibition gives shape and life to the concepts of Hip-Hop Architecture: a form of study and practice that addresses historical inequities and structural racism within the fields of architecture and urban planning by centering hip-hop as both a vibrant—and dominant—form of culture and mode of being. On view through March 12, the exhibit features work from artists, architects, academics, and designers including Lauren Halsey, James Garrett Jr., Olalekan Jeyifous, and Amanda Williams (a 2021 Women in Architecture honoree and 2022 MacArthur Foundation fellow).

Born in Jamaica and based in Charlotte, North Carolina, Cooke holds a B.Arch from Cornell University and an M.Arch from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. He is currently the director of the Master of Urban Design program at University of North Carolina at Charlotte and the principal at sekou cooke STUDIO.

Peter L’Official, an associate professor of literature at Bard College—whose 2020 book Urban Legends explores hip-hop’s origins in the South Bronx and the twin narratives of urban crisis and cultural renaissance—spoke with Cooke for RECORD about the significance of the exhibit’s current locale in Atlanta and the evolving codification of Black culture within architecture.

1

2

Museum of Hip Hop (2017) by Michael Muchmore (1), HHA Signifying Project (1993) by Nate Williams (2). Images courtesy the artists

"Hip-Hop Architecture" pays homage to the South Bronx, the birthplace of hip-hop and a place that gave us some of the most lasting images of what America understood as the “urban crisis” in the 1970s and 1980s. If Hip-Hop Architecture was also born—spiritually and culturally—in the built environment of South Bronx, what does it mean to open this exhibition in Atlanta, a place that New York Times music reporter Joe Coscarelli has called in his recent book, Rap Capital: An Atlanta Story (2022), “the most consequential musical ecosystem of this century so far?”

Having the exhibit in Atlanta is a powerful step because it is this new center of hip-hop culture, which I wasn't even fully aware of when the show was originally being planned. The dialogue between the context of the South Bronx—its environments and the sound coming out of it at that time—and what's happening now in Atlanta in terms of development and growth, not just as the center of hip-hop culture, but of Black wealth in the country, I think strikes a really important arc across time and place; it also connects the physical destruction and decrepitude of what the South Bronx once was to the kinds of futures and developmental expressiveness that Atlanta represents right now.

I was struck by a line in your book [Hip-Hop Architecture, 2021], where you say, “Many have managed to exist simultaneously as successful architects and Black. Few have managed to express their Blackness through their architecture. Within hip-hop culture lies the blueprint for an architecture that is authentically Black with the power to upend the racist structures within the architectural establishment and ignite a new paradigm of creative production.” Toni Morrison’s foreword to The Bluest Eye (1970) discusses her own struggle for writing that was “indisputably black,” and how her unapologetic use of codes embedded in Black culture—without any explanatory scaffolding—were her way of trying to “transfigure the complexity and wealth of Black American culture into a language worthy of the culture.” Does Hip-Hop Architecture also strive for an architecture that is, after Morrison, “indisputably black?”

In my book, I talk about the codifying of language, and of graffiti as a code, and the “if you know, you know, and if you don't know, you better ask somebody” attitude that's embedded within hip-hop. This is a critical tool for translating that hip-hop attitude into architecture because architecture has understood coded language for centuries. Some of them were divine codes from the Egyptians, the Greeks, the Romans, and some of them are codes embedded within a linguistic structure that's only recognizable to architects that understand order and structure. The problem with that is that it sets the architect up on a pedestal as this divine, decoding authority. Hip-hop uses that same internal referencing structure but does so in order to dismantle those power structures—and that comes directly from slave communications. We had to talk in code, or we’d be discovered, or even lynched.

Many previous attempts at reifying Blackness within architecture have leaned heavily on the aesthetic, but the architecture doesn't change functionally, or formally. And the problem with images is that they can be easily co-opted. So understanding the codes of what created that image, and embedding those codes within your process and within your attitude towards the design, is much more impactful, and much more authentically Black, than anything that is more on the surface. And hip-hop is the blueprint for that.

.-Photo_-courtesy-of-the-artist-and-David-Kordansky-Gallery_result2.webp)

Crenshaw District Hieroglyph Project (2016) by Lauren Halsey. Image courtesy the artist and David Kordansky Gallery

I know that you've been asked many times to define “Hip-Hop Architecture,” which I'm not going to ask you to do.

[Laughter]

Instead, I’m going to read you a short quote from the drummer Max Roach: “Jazz is to me a nickname. It's not the proper name for African American instrumental music…It never was a name that we as musicians gave to it…All the techniques that I acquired, I try to apply in the tradition of people in the African American instrumental tradition.” Does that resonate with you in terms of your understanding of Hip-Hop Architecture, and to your own practice as an architect, teacher, and curator?

Naming anything is an inherently colonialist act. We want to control this thing, and in order to control it, we have to name it. It's like planting a flag. And the truth is, we can't own anything. We're only stewards of land, of possessions, of money. It all moves and all changes. We think we know that we're saying the same thing, but in reality, you attach a different meaning to every single word that you use because you come from a different understanding of what that word means. So when I say “hip-hop,” it's not the same thing as when you say “hip-hop.” When I say “architecture,” it’s not the same thing as when you say “architecture.” I went through many phases early on when I thought about not even using the term Hip-Hop Architecture, but that was a commercial decision to make it easy enough for people to understand, but provocative enough for them to be brought in.

Hip-hop had to make that decision too.

Exactly. Hip-hop had to make that decision to make itself commercial. Hip-hop understands capitalism probably better than any other institution in the United States. But I'm not trying to own “Hip-Hop Architecture” as a category. I'm just seeing patterns, understanding trends, and packaging them into something that people can understand—and more importantly, so people working in that way can have pride that they are anchored into a larger conversation that's been going on for 30 years.

To not feel as if you're at sea, yes?

I remember being a student and, with my fellow Black or brown students, being afraid of expressing our identity within our work because there was a deep fear that not only would it not be accepted, but that we would also be ridiculed for it. Today, you have a whole body of research that has been around for years. Before me, for instance, Craig Wilkins [among others] was doing this work. Now, students can be evaluated based on the merit of their own interpretations.

-by-Olalekan-Jeyifous-2015.-Image-Courtesy-of-Olalekan-Jeyifous_result2.webp)