In Focus

Studio Joseph Creates a Vibrant East Harlem Haven for a New York Animal Shelter

New York City

A quiet block in Manhattan’s East Harlem neighborhood lined with understated residential walk-ups is an unlikely place to encounter an attention-grabbing kaleidoscope of color. But on East 109th Street, between First and Second avenues, what was once a shabby garage from the 1930s has been transformed into an eye-catching landmark for the neighborhood. The steel rainscreen that now shields the existing masonry is painted to create a lenticular effect, appearing blue-gray when encountered head-on. But alter your viewing angle, and it shifts from yellow and cool green to deep blue and purple and back again. This chromatic play offers little clue to what’s inside: a 2,500-square-foot pet-adoption outpost operated by the Animal Care Centers of New York (ACC), the city’s largest animal shelter.

The 1939-built former garage (above), and the existing masonry covered by a brightly painted steel rainscreen (top of page). Photo © Alex Fradkin, click to enlarge.

Opened in October one block south of ACC’s bulky and imposing Manhattan headquarters, the center was designed by New York–based Studio Joseph. According to firm principal Wendy Evans Joseph, the nearly century-old garage was in bad shape, its wood roof structure damaged and concrete-slab floor cracked. The design team considered tearing it down entirely, but the existing square footage was adequate for the ACC’s needs and the organization wanted to be a good neighbor.

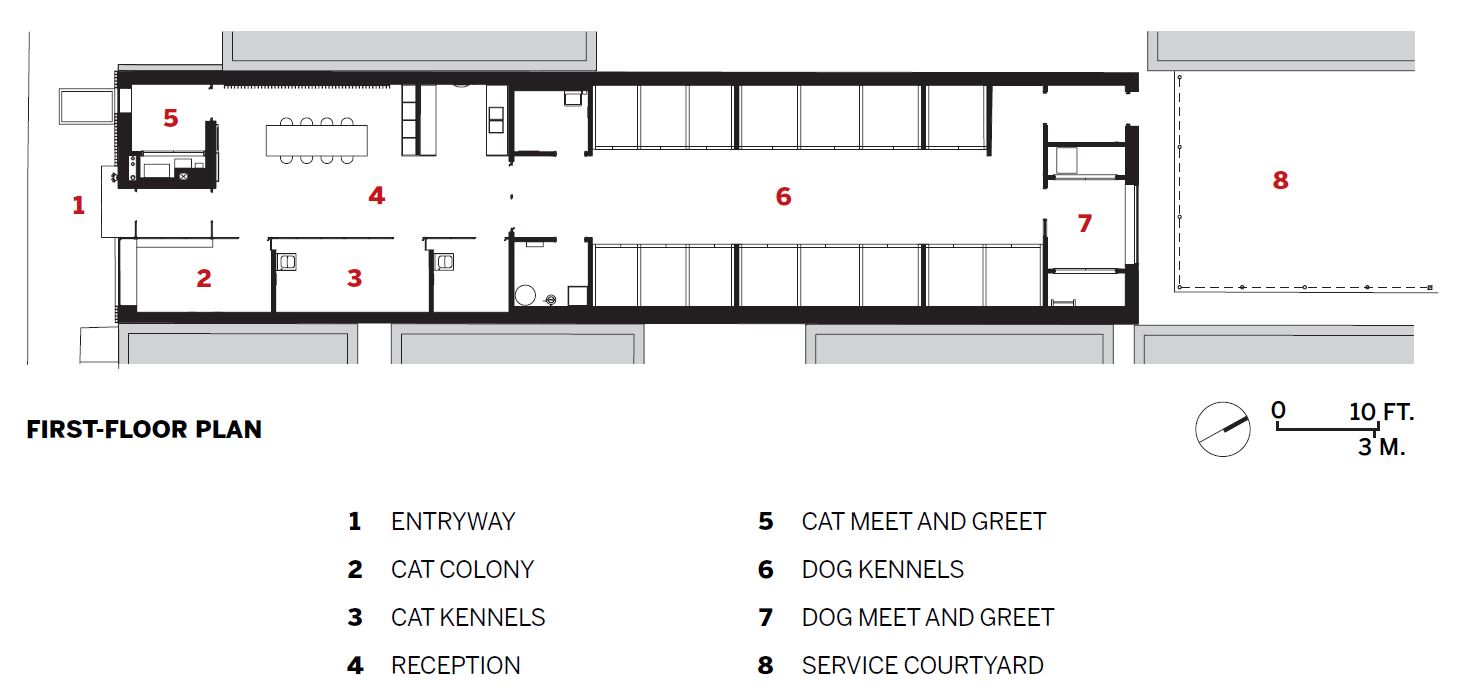

Studio Joseph’s plans kept as much of the original structure as possible, bracing the original wood beams and working within the building’s brick envelope. The two garage doors at the front and back were transformed into glass-fronted entryways, and the adjacent doors became windows for the respective dog and cat meet-and-greet rooms—housed at either end of the building to avoid unpleasant interspecies encounters. The two original skylights, which run the length of the building, were preserved and embraced as the center’s spine of circulation, creating a more pleasant environment for both human and animal guests than the fluorescent-lit and cramped interiors of the nearby headquarters. “Bringing daylight into both the lobby and the kennel area gives the animals a sense of night and day,” says Joseph. “It’s very healthy for them and lends them a calmer spirit.”

The bulk of Studio Joseph’s work is dedicated to cultural projects, and this background informed the project’s statement-making facade and its warm interior atmosphere. A large rectangular reception desk greeting potential adopters stretches along the length of the lobby space. Above it is a large mural, also designed by Studio Joseph, that mirrors the effect of the facade, portraying a dog when seen from one angle and a cat from another.

The feline quarters adjoin the reception area, which cultivates a welcoming atmosphere with a communal table and a playful mural. Photo © Alex Fradkin

The front half of the building is dedicated to cats, which have a street-facing “condo” room for play and socialization and an adjacent kennel room with individual habitats that can accommodate up to 28 felines. The center’s 15 dog kennels, home to its noisier inhabitants, lie through a door beyond the lobby. To avoid aggression between the hounds, Studio Joseph developed a special frit for the glass kennel doors, in consultation with animal-behavior specialists from the ACC. Its diamond pattern becomes denser at the lower reaches, preventing the animals from seeing each other from across the narrow corridor, while allowing humans to look in from above. This overlay is also present on all street-facing windows, letting the cats in the colony observe the outside world while maintaining privacy.

Animal-facing glazing is adorned with a specially designed frit, which becomes denser at the lower reaches. Photo © Alex Fradkin

The need for a happy environment for animals—and a welcoming one for visitors—was challenged by the technical nature of the project. “It was almost like doing a medical facility,” says Joseph. “Everything has a highly specialized purpose.” The building’s bulky mechanicals, needed to maintain air quality and an extensive hose system, are hidden in a drop ceiling. Further balance had to be struck between health and safety standards for both animals and humans. For instance, the concrete floors, which contain drains for easy cleaning, needed enough grit to prevent humans from slipping when wet but not so much that it would hurt the animals’ paws.

The fetching new adoption center addresses a larger need for the organization. Its contract with the city mandates that it accept every and any animal brought in—dogs and cats, but also guinea pigs, rabbits, injured wildlife, and confiscated exotic pets. With three full-service locations, in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Staten Island, the ACC takes in an average of 5,000 dogs and 10,000 cats annually. During the pandemic, as household budgets tightened and the city’s housing crisis deepened, intake increased so dramatically that it threw the organization into crisis. In the summer of 2023, ACC, for the first time in its history, announced it had run out of space and was closed for surrenders. Its 109th Street outpost is part of a larger plan that addresses the organization’s space crisis; it will include new facilities in Queens and the Bronx as well as the renovation of existing care centers.

According to an ACC staff member, animals are moving through the new center at a much faster rate than in the main facility, the average length of stay being about 14 days, as opposed to 20. While more ambitious long-term plans come to fruition, this relatively modest intervention, working within the constraints of an existing structure and a tight urban site, offers a compelling and budget-friendly prototype for future facilities, balancing function and comfort for all creatures, great and small.

Click plan to enlarge