Renovation, Restoration, & Adaptive Reuse: 2025

Pictet + Broillet Adapts a 19th-Century Hayloft for the Collection du Crest

Jussy, Switzerland

Architects & Firms

Perched on a spur in rolling countryside northeast of Geneva, the 17th-century Château du Crest is a fortified manor house bristling with turrets and pointed roofs. Bought by the Micheli family in 1637, the estate comprises a large farm, today famed for its wine and its pork products. Besides managing his legacy, the current chatelain, 87-year-old Yves Micheli, has spent his life collecting pictures—in particular, landscapes—painted by members of the Geneva school or by artists associated with the city. In the late 2010s, looking to ensure the future of his collection, which counts around 300 works, he set up a foundation and charged architect Charles Pictet, of Geneva-based office Pictet + Broillet, with converting a disused hayloft to display them. Curated by art historians, the museum is open to the public two days a week, and continues to acquire works to strengthen its holdings, which span the period 1720 to 1970.

Serried rows of hanging cowbells announce the entrance and main stairwell leading to the Collection du Crest. Photo © Duccio Malagamba, click to enlarge.

“To a certain extent, it was up to me to invent the program,” recalls Pictet of the commission. Located in the farmyard next to the château, the timber hayloft occupied the second level of a 19th-century stone cow barn that had been rebuilt after a major fire in 1989. With its concrete-block and rubble-stone walls, dark timber siding, and deep eaves, the building is the picture of idyllic rusticity. While its ground floor now accommodates wine bottling and farm-related storage, “all you saw upstairs was a huge void rising into the rafters, with the undersides of the roof tiles exposed,” as Pictet remembers. His first challenge was to get visitors up to the new museum. Located in the farmyard, at the center of the barn’s shorter, eastern side, the entrance is surmounted by serried rows of cowbells, and takes the form of a generous vestibule, at whose rear rise a stair and elevator (in concrete, to satisfy fire regulations). Fitted with wood doors that swing back flush with its lateral walls, the vestibule remains entirely open to the outside during museum hours. In a nod to context, the doors’ internal surfaces, along with most of the stairwell, are faced with the same corrugated white-metal siding used for the farm’s wine-refrigeration sheds.

Movable partitions offer flexibility for display and events. Photo © Duccio Malagamba

Corrugated sheet metal lines the stairwell. Photo © Duccio Malagamba

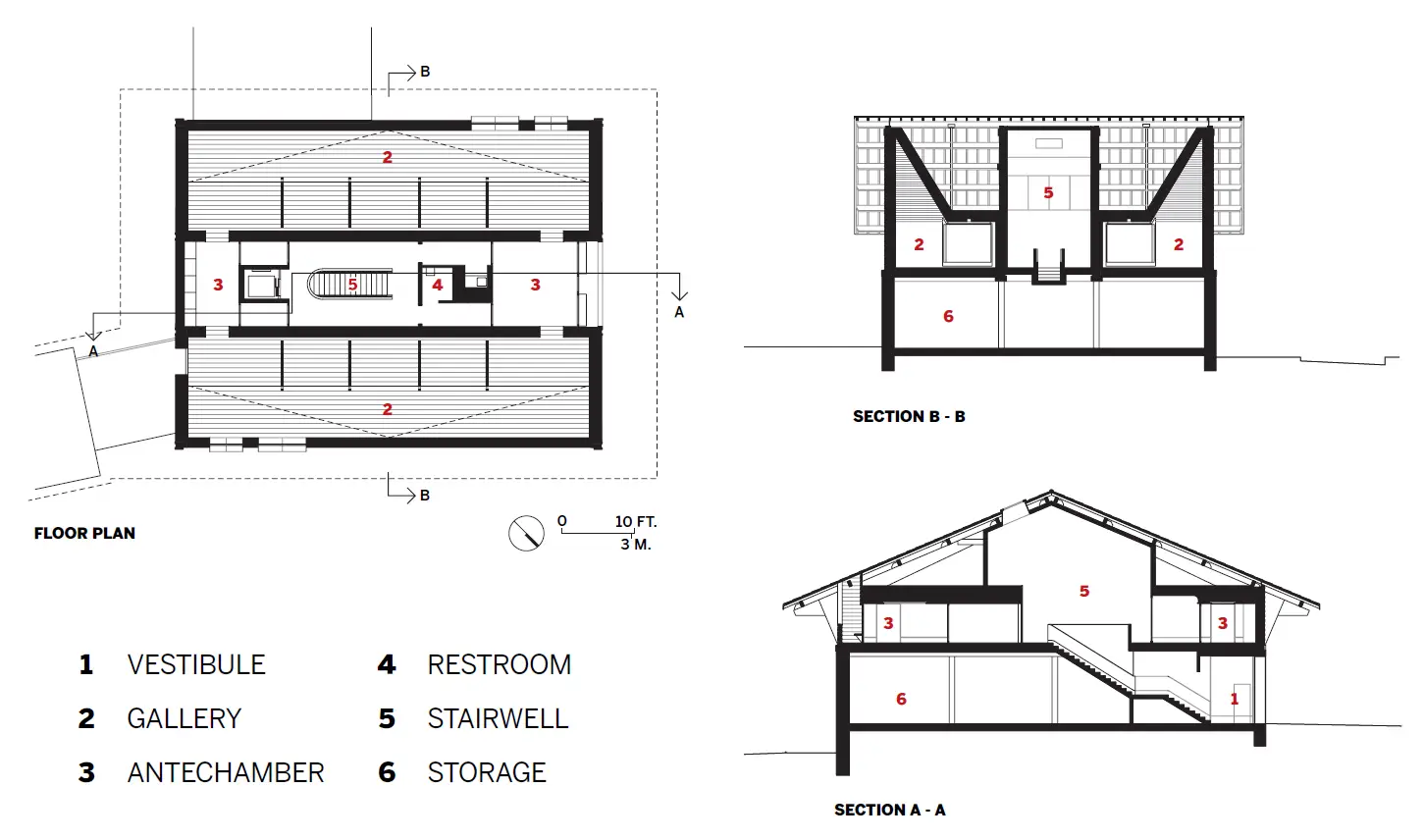

Rising to the apex of the barn’s roof, the lofty stairwell receives daylight from an opening at its summit, encouraging visitors to move upward. In contrast, past the turnstile on the landing, a windowless, low-ceilinged antechamber greets them in the museum proper, fitted out with bespoke coat-check closets. This sequence of alternating expansion and contraction continues as visitors proceed into the soaring volume of the first gallery, which runs down the hayloft’s gable wall on its longer, southern side. Contrary to expectation, the gallery ceiling slopes sharply downward from the gable’s apex, before flattening out to form a low, partition-filled aisle. “Given its huge size, the barn’s roof would have been very costly to redo, so I sought a way of leaving the envelope intact,” explains Pictet with respect to the dropped ceiling, which, insulated to stringent Swiss standards, dissimulates museum-grade HVAC in the void above it.

Photo © Duccio Malagamba

Pictures hang on both the perimeter walls and the partitions; suspended from the flat ceiling, the latter can slide up and down the length of the gallery. “By moving them close, you have an intimate cabinet de dessins; widening the gap, you obtain a space for landscapes or portraits; and by pushing them all to one end, you open up the gallery for concerts or lectures,” says Pictet of this flexible system. Once again, daylight draws visitors forward, this time thanks to a pair of full-height lozenge-shaped windows at the far end. “While the reconstructed barn had no particular story to tell, it offered exceptional views across the landscape, which is to some extent the subject of this museum,” explains Pictet, who deliberately delayed this encounter with the exterior to preserve contemplation of the paintings. “On arriving at the windows, visitors find themselves framed in the landscape itself,” says the architect. Outside, the diamond openings echo the château’s pointy silhouette, serving to indicate that this is no ordinary barn, while, inside, they become something of a leitmotif, since the HVAC vents and ceiling recesses for concealed lighting are also diamond-shaped.

Lozenge-shaped apertures punctuate the facade. Photo © Duccio Malagamba

Contraction and expansion continue when passing from the south gallery to the north, since visitors traverse a low space at the barn’s western end that gives onto a balcony. On the opposite wall, a screen shows videos and information about the collection, with a small kitchen and stockroom tucked away behind. Although the north gallery is essentially identical to the south, the atmosphere is different, partly due to the colder light but also to a change in color: eau de Nil in the south gallery, the partitions are gray-beige in the north. “These pictures were made for homes, so I didn’t want a white cube,” explains Pictet. “I aimed for both a domestic scale and a spatial generosity and pleasure.” Materials (natural fir floors, white-painted wood ceilings) and detailing (the alternate orientation of closet handles, triangular “acroteria” on the partitions) reflect a certain “pursuit of sensuality” in a simple yet sophisticated interior. “This is a little, provincial museum, but I wanted people to remember it,” says Pictet, and the sense of place, at once delightful and idiosyncratic, is indeed palpable.

Click drawings to enlarge

Credits

Architect:

Pictet + Broillet Architectes — Charles Pictet, Baptiste Broillet, partners; Daniel Gibbons, director; Henri Favre, project manager

Engineer:

B.Ott et C.Uldry SARL (structural)

Client:

Fondation Musée du Crest

Size:

4,790 square feet

Cost:

$4.28 million

Completion Date:

November 2023

Sources

Masonry:

D’Orlando

Curtain Wall/Windows:

Serrurerie 2000

Doors:

Dasta

Interior Finishes:

Ateliers Quetzal (paints/stains); Parquets Plus (tile)

Lighting:

Erco (downlights)