Unlike many of the prefabricated accessory dwelling units (ADUs) flooding the California market, the Polyhaus does not fit on a flatbed truck fully assembled. The polyhedron-shaped house was conceived by Daniel López-Pérez as a solution for expediently producing quality housing at scale in the smallest footprint possible, rather than as a rectangular box for ease of shipping. With his wife and Polyhaus LLC cofounder, Celine Vargas, López-Pérez built the first two-story, 540-square-foot proof-of-concept in 2024 in the backyard of the couple’s 1962 Palmer & Krisel house, in San Diego.

The first Polyhaus (above and top of page), a 540-square-foot, two-story metal-clad and CLT structure, was built last year in San Diego. Photo © Andy Cross and Cody Cloud, click to enlarge.

López-Pérez, who is professor and architecture-program director at the University of San Diego, developed the Polyhaus system by starting with a simple cube and then repeatedly truncating the edges until he optimized the form for the largest volume and smallest footprint. The 440-square-foot ground floor includes a living room, kitchen, bathroom, and nook for a desk and washer/dryer, with the bedroom on the 100-square-foot mezzanine. “Polyhaus is a design and construction-technology company,” says López-Pérez, which he contrasts to ADU manufacturers that provide a built product. The couple view their 17-foot, 4-inch-tall Polyhaus as a research-and-development investment to bring the timber innovations revolutionizing large-scale construction down to smaller scales.

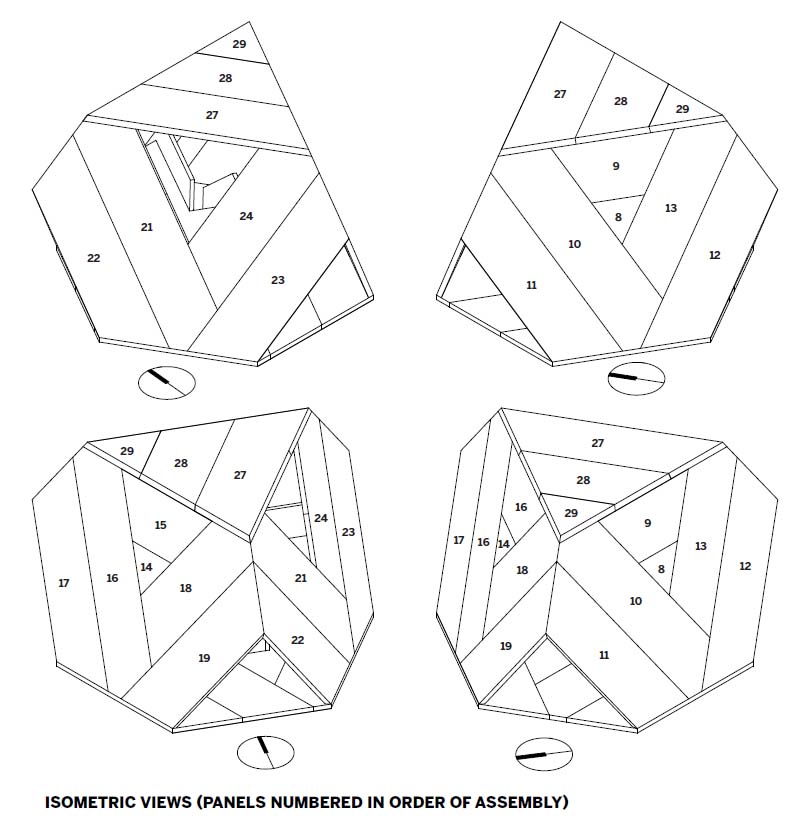

The house’s primary structure and envelope consist of 64 individually cut Douglas fir cross-laminated-timber (CLT) panels, produced by Vaagen Timbers in Colville, Washington. López-Pérez says the structural engineer, Fast + Epp, from Vancouver, British Columbia, estimated that the nonlinear structure of the CLT panels provides significant redundancy compared to a simple stud-framed house. The floor panels are five ply, 7½ inches thick, while the rest are three ply, 4½ inches. “The virtue of this truncated polyhedron shape is that we have 25 panel shapes that repeat themselves, so it reduces details immensely,” says López-Pérez. In his view, the project has only two architectural details—the structural connections fastened with bolted metal plates, and the simpler splines between panels that slot together.

Site preparation took one week, which included pouring a concrete foundation stem wall. Electrical and plumbing services were installed under the floor and extend up to two conventionally framed walls serving the kitchen and the bathroom. With the platform floor installed, work could begin on piecing the walls together until they formed a self-supporting diaphragm. Vaagen stacked each panel on the truck in the order in which it would be unloaded with a crane and set into place. Installation of the panels took a crew of three workers only three days on-site. Following that, a vapor barrier was applied, seams sealed, and Kingspan insulated metal panels were screwed directly into the CLT.

A predictable, kit-of-parts supply line helped the couple reduce the price significantly, with the smallest model costing approximately $300,000—including San Diego permitting and other development fees—with a construction schedule of 12 weeks, from site work to turning the key in the door. The couple estimates 40 percent of that cost is labor. “We scheduled each trade separately for this project, but we were also testing things as we went through construction,” Vargas says. One way to save time would be to eliminate the concrete-foundation requirement, which the couple allowed for by also pre-permitting a version of the house that sits on 26 earth screws. Vargas estimates they could get the construction time down to eight weeks or less. Building a single-family house can easily cost between $600 to $1,200 per square foot in California, compared to $550 per square foot for Polyhaus, which is comparable to more conventional ADUs.

The couple recently secured a patent for the Polyhaus system, and plan to offer a business model for licensing the technology to builders this year. Vargas says, given San Diego’s lack of housing supply, the licensing model would allow them to accelerate production. They also envision small-scale developers, who could build six or more on a lot, as the primary market. Since California land costs are so high, López-Pérez suggests that infill lots could be developed along the lines of a bungalow court, providing a “missing middle” with a density between apartment buildings and houses. “It would open up the possibility of houses that are more flexible to multigenerational families,” he says, “with people at different stages in life.”

Click graphic to enlarge