Interdependence is the key ingredient of On Olive, a development at the edge of downtown St. Louis that cultivates semi-communal living as an art form. The project’s first phase of 17 houses is a collaboration between the philanthropist Emily Pulitzer, who is intent on city-building through art; the architect Tatiana Bilbao, who set up the site plan to challenge residents to embrace an unusually intimate form of collective habitation; and a cadre of architects—MOS, Productora, and Estudio Macías Peredo—who have honed a repertoire of spatial moves that build community one relationship at a time.

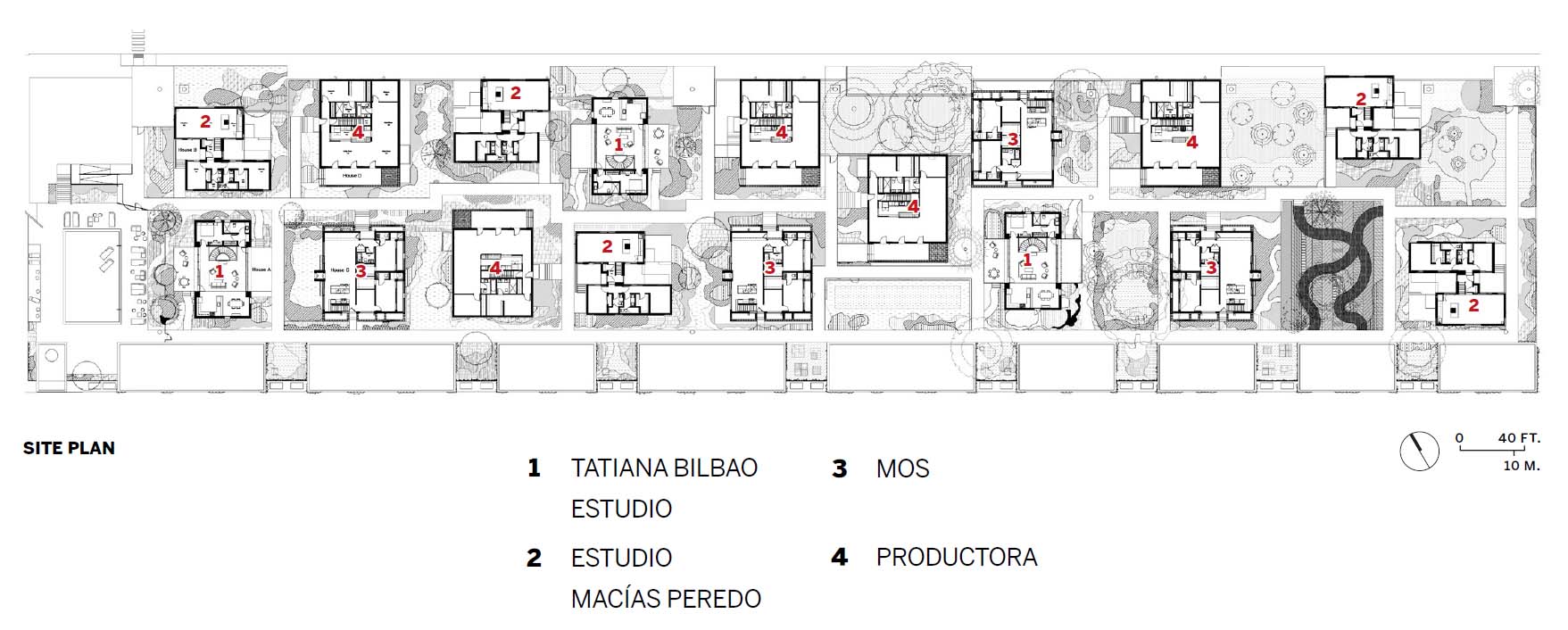

Many common housing types, such as condo towers and suburban tracts, often fail to foster interaction—they lack the kinds of small spaces that, shared by two or three residents, require neighborly negotiation. On Olive provides these spaces in abundance. Since the initial master plan was drafted in 2018, the idea was to take a site that would normally be divided among eight two-story houses and to disassemble them into a collection of twice as many one-story dwellings, which Bilbao jostled around on a shared landscape of paths, gardens, patios, and parkettes in lieu of the typical front and back yards. (Among the programmed outdoor areas are a dog park, a swimming pool, and an herb garden.) The result—even with three two-story houses in the mix, plus a few condos in a renovated warehouse at the edge of the site—is akin to a live-in artwork in the genre known as relational aesthetics, a contemporary form of participatory art exemplified by Rirkrit Tiravanija’s pad thai, an artwork that invited gallery-goers to cook and eat a meal together. The strategy of On Olive is to bring this sort of thoughtful co-creation to the realm of cohabitation.

Amid the lush greenery, Productora’s ziggurat forms sit next to MOS’s chimney-defined structure (above) and the cantilevering exterior of Tatiana Bilbao’s house (top of page). Photo © Attilio D’Agostino, click to enlarge.

On Olive was instigated by Pulitzer, who also established the nearby Pulitzer Arts Foundation, in a bid to draw people back to the city center following decades of depopulation. The surrounding Grand Center Arts District is home to palatial historic theaters as well as the foundation’s art museum, located a block away in a building designed by Tadao Ando and completed in 2001. In Bilbao, Pulitzer found a kindred spirit.

An interior by Tatiana Bilbao. Photo © Onnis Luque

Bilbao posed a practical question to the architects who were invited to shape the community: “How can we orchestrate interdependence?” At On Olive, the first step is shared ownership. While the houses and a few feet of greenery around them are owned by individual residents, the remainder belongs collectively to the homeowners’ association. Invisible lines run between, making the land feel shared even when legal boundaries say otherwise. Bilbao imagines not stark spatial divisions but layers of inhabitation, from the bedroom to the sidewalk: “Our idea was to have intimate spaces, semi-intimate spaces, and shared intimate spaces—then shared common spaces, shared collective spaces, and public spaces.”

Creating a new neighborhood from scratch is difficult, and it requires a taste for experimentation. The market seems to favor either custom houses or spec buildings, which skew respectively toward the idiosyncratic or the generic. The premise of On Olive was to commission architects who normally design one-off residences to instead design a model house, more or less, that would be built a few times.

A sculptural staircase inside a house by Tatiana Bilbao. Photo © Attilio D’Agostino

Quite intentionally, such fine-tuned staging of conviviality is familiar to the four architects who designed the houses. Wonne Ickx, of Productora, emphasized “spatial generosity.” The house his team designed is a 40-foot-square volume with a 20-foot-square core comprising the kitchen, bathrooms, and basement stairs, all open above to a clerestory box. (Yes, it’s a two-tier ziggurat form.) Ickx describes how the resulting “kaleidoscopic three-dimensional complexity” is meant to be adapted to suit residents’ tastes. The aim was a more relaxed relationship to the architect, he explains, so that “the designer doesn’t need to control everything.” It’s a participatory project “and a sort of a provocation to see if it’s possible to create a co-living community,” he adds.

Asked how On Olive might serve as a model for future housing developments, Hilary Sample of MOS speculated that “incompleteness” invites participation. More broadly, Sample suggests that the idea of housing evolved during the project as a result of more people working from home and, perhaps, a more subtle shift in cultural values. MOS designed bedrooms in its houses to be the same size, for example. “Equity begins at home,” Sample says, and she projects a more modest approach to housing in years ahead. Ranging from 1,460 to 1,690 square feet (excluding the basement), On Olive homes are well below the U.S. average of about 2,500.

This willingness to “go against the market,” as Sample puts it, was possible because Pulitzer covered some major up-front costs. Existing decrepit houses were cleared, the site regraded, and bioswales installed to control drainage. This essentially reset the equations such that the site could be developed within market parameters—funding the experiment rather than subsidizing the houses, in a way. Improved water management will benefit adjacent sites as well, and the development of On Olive itself will continue. The next phase, across the street, will have houses by Constance Vale, Cory Henry, and Höweler + Yoon, and a final zigzagging composition of townhouses and apartments by Michael Maltzan Architecture is slated to follow.

1

2

The next phase will feature residences by Michael Maltzan (1) and Höweler + Yoon (2). Images © Michael Maltzan Architecture (1); Höweler + Yoon (2)

On Olive has come together as a coherent scheme of blocky masses. The limited palette of bricks used for walls and paths helps, but more important is how everyone adhered to Bilbao’s plan, working together just as cooperatively as she and Pulitzer hope the community iself will function, creating a set of spaces that function in an extraordinary way. From many rooms in any of the houses, residents can look out across a patio, into a garden, along a path, onto a terrace, and into another similar room in another house only 10 yards away. The architects had to pay close attention to who can see what, and when, and where as they designed their spaces, and to respond nimbly to this topography of interdependence.

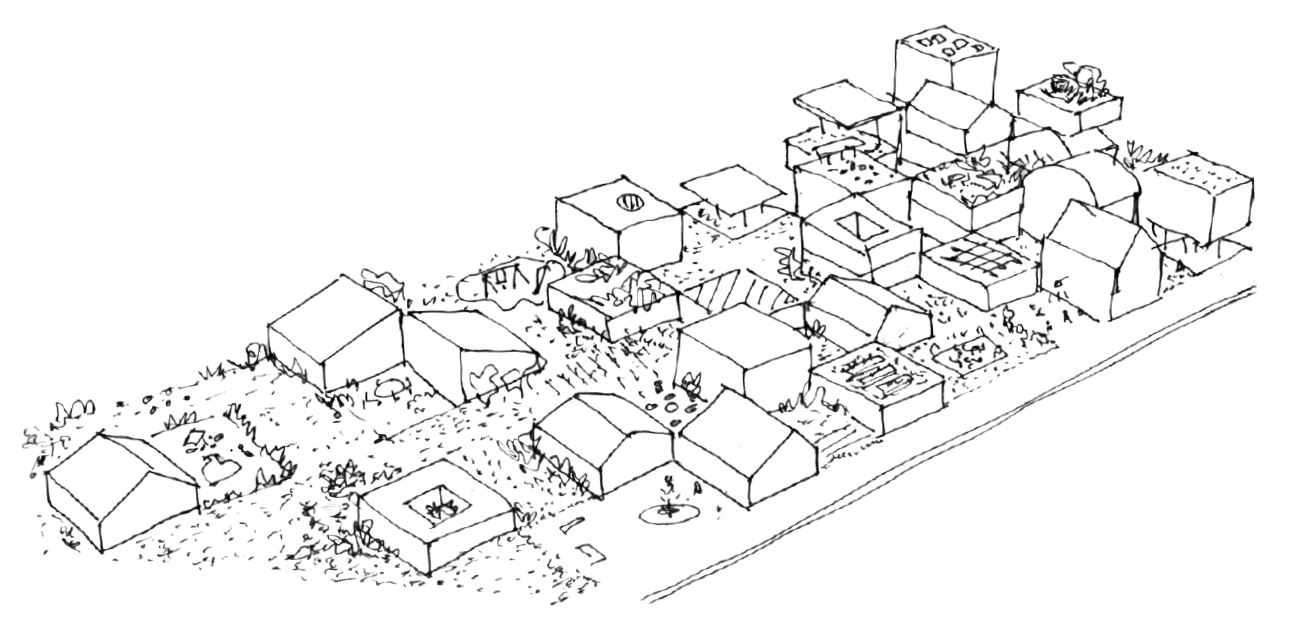

Initial sketches of the master plan depicted a looser and varied organization, with more compact houses amid larger fields of green. As built, the more expansive footprints could have made the buildings feel oppressively dominant. Uniformity alleviated this problem. With all the architects playing along in the creation of stacked rectilinear brick volumes, the ensemble coheres as a backdrop against which details add pops of character. The orange flashing on some Productora houses, for instance, stands just enough to resonate with the theme of collective choice.

Tatiana Bilbao’s concept sketch of the development. Image © Tatiana Bilbao Estudio

Pulitzer’s curatorial sensibility can be felt throughout. Spolia amid the shrubbery recall the history of site, from a pile of Corinthian capitals hinting at an era of opulence to a lone steel column suggesting both an industrial past and—with a nod to abstract minimalist sculpture—a more artistically attuned future. As we strolled through the site with construction of the first phase nearing completion, there was one word she had for everyone: simplify. This would probably be her advice in galleries as well. By not calling attention to themselves, the architects of On Olive have set the stage for other lives to flourish.

A lone steel column rests beside Macías Peredo’s houses. Photo © Attilio D’Agostino

Click plan to enlarge