After Accelerated but Incomplete Reconstruction, Notre-Dame de Paris Reopens to the Public

Right from the start, French president Emmanuel Macron has defined himself as the maître des horloges—master of time—for his refusal to let anyone set his deadlines. Cornered, he slows the clock down—67 long days to appoint a prime minister after this year’s parliamentary elections; ebullient, he speeds it up—just three weeks to organize those elections, and only five years to rebuild the Cathedral of Notre-Dame after the disastrous 2019 fire that destroyed its roof and spire and very nearly brought the whole building crashing down. In the wake of Macron’s surprise announcement, which he made the evening after the April 15 disaster, many denounced the timeline’s arbitrariness and dismissed such haste as unfeasible. But, armed with the almost $900 million showered on the cathedral by donors big and small, France has just about pulled it off: though work won’t finally complete until 2028 at the earliest (scaffolding still shrouds much of the exterior), Notre-Dame reopened with great state and ecclesiastical pomp this past weekend, five years and not quite eight months after the blaze.

Exterior view of the cathedral taken in mid-November. Photo by David Bordes © Rebâtir Notre-Dame de Paris

In the aftermath of the catastrophe, as efforts began to stabilize the building (a heroic process that would take more than two years), a controversy blew up that pitted ancients against moderns. For the latter, President Macron among them, the 21st century should leave its mark on the cathedral by, for example, rebuilding with today’s technology, or adding a new, contemporary spire. The traditionalists, on the other hand, wanted everything put back just as it was. Thanks, primarily, to France’s strict historic-monument legislation, the conservation lobby won the battle early on: in the spirit of the 1964 Charter of Venice, Notre-Dame has been returned to its last-known state, a battalion of skilled craft workers having faithfully recreated Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc’s 1859 lead-and-oak spire and reconstructed the medieval roof, also in oak, using traditional hand techniques. Damaged vaults have been repaired, every single chapel cleaned and renovated, the 7,952-pipe main organ taken apart and put back together, and all surfaces, objects, and furnishings cleaned and, where necessary, restored. One feature the cathedral’s medieval and 19th-century builders would not recognize, however, is the state-of-the art fire-detection system that now protects the “forest,” as the roof frame, hewn from over 1,000 oaks, is known.

1

2

Restoration of the chapel wall paintings (1); the cathedral's 13 chandeliers and many restored wall sconces were reinstalled this October (2). Photos by David Bordes © Rebâtir Notre-Dame de Paris

Despite winning all the main battles, conservationists continue to dispute the clergy’s decision to replace six of Viollet-le-Duc’s windows in the south-aisle chapels with contemporary creations—the church argues that the stained-glass craft tradition must be renewed to stay alive. The move is supported by Macron, who proposes displaying the demounted grisailles, as Viollet-le-Duc’s ornamental, non-figurative windows are known, in the future Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame, a new museum that will tell the cathedral’s story from construction to restoration. Conservationists say Viollet-le-Duc’s designs, which he modeled on medieval originals at Bourges Cathedral, are part of a carefully considered whole; modernizers claim they are not only unremarkable but have lost all meaning given that much of the painted décor they once complemented was long ago erased. An international competition, chaired by former Centre Pompidou head Bernard Blistène and currently in its second round, has seen French artists Daniel Buren (a presidential favorite) and Philippe Parreno, as well as the Chinese painter Yan Pei-Ming, submit window designs.

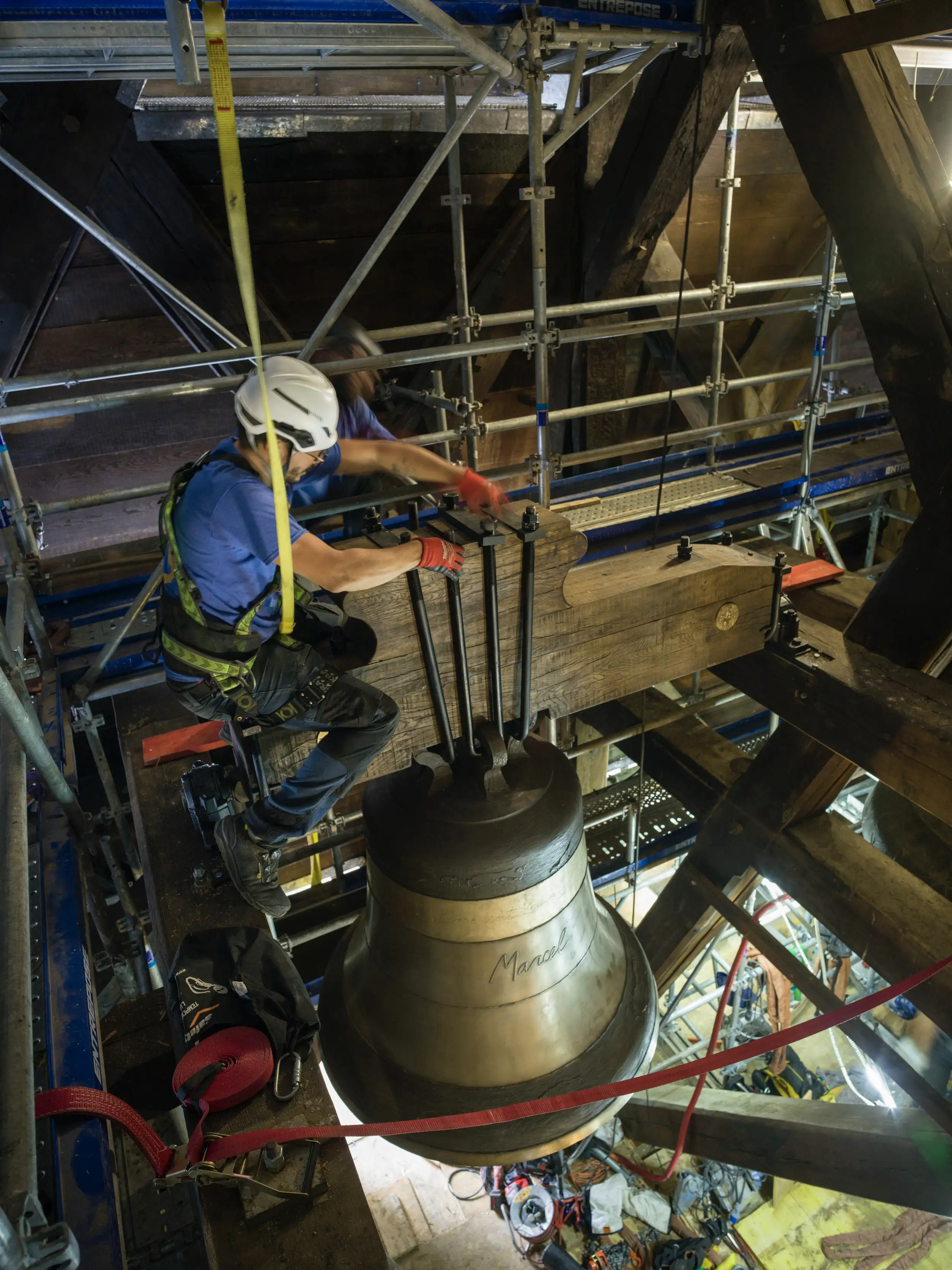

The eight bells of the north belfry were removed, restored, and replaced in September. Photo by David Bordes © Rebâtir Notre-Dame de Paris

Whatever happens in the south aisle, contemporary design has now found its way into the restored cathedral. One example is Guillaume Bardet’s new bronze furnishings, including the lectern and the high altar, and his liturgical accessories in silver and gold, whose calm sober lines respond to a request for “silence” from the church authorities. The same goes for Ionna Vautrin’s 1,500 new congregational chairs, as well as her benches and prie-dieux (kneeling benches for prayer), which are all in oak. Meanwhile, fashion designer Jean-Charles de Castelbajac’s vestments add a burst of Pop color with their splashes of red, blue, and yellow on an ivory background, though even these are discreet enough to avoid ruffling conservationist feathers. Where visitors will find the cathedral very changed is in the whiteness of its limestone interiors, formerly blackened by a century and a half of grime, and the new ambient lighting, designed by the self-styled “light sculptor” Patrick Rimoux. With 1,400 individually programmable LED units deployed all over the interior, a vast palette of moods is now possible, from “architectural” and “concert”—each with ten configurations—to “liturgical,” for which there are over 30 different scenarios.

.webp)

The cross was placed atop the spire in December 2023. Photo by David Bordes © Rebâtir Notre-Dame de Paris

The oak base of the spire was craned into place in spring 2023. Photo by David Bordes © Rebâtir Notre-Dame de Paris

None of these modernization attempts are to the taste of Philippe Villeneuve, the government-appointed heritage architect who has been in charge of Notre-Dame since 2013, and who was busy restoring the spire when the fire broke out. A Viollet-le-Duc fanatic—to the point where he has his forebear’s spire design tattooed on his left arm—he tried, and failed, to restitute the 19th-century lighting system. Instead, he has had to make do with putting things back as they were before the blaze: Viollet-le-Duc’s elaborate, waxed-bronze chandeliers, originally suspended in the main vessel, have stayed put in the arcades, where they were moved after electrification in 1905, while his “crown of light,” which until 2004 hung in the crossing, has remained at the former abbey church of Saint-Denis, where it arrived in 2014, ten years after the then archbishop took it down for “liturgical reasons.” Certain conservationists accuse the clergy of waging a long and stubborn war against Viollet-le-Duc’s legacy.

In May, the 39-foot-tall chevet cross, damaged during the 2019 fire, was lifted to its place at the tip of the apse. David Bordes © Rebâtir Notre-Dame de Paris

Nonetheless, these sectarian querelles de chapelle cannot detract from the enormous achievement represented by the exceptional restoration effort at Notre-Dame, especially given the very difficult conditions in which it was carried out. Progress slowed not only due to two years of COVID but also because of the vast quantities of vaporized lead that had settled in the form of dust all over the cathedral and its surroundings, necessitating reinforced safety measures for the duration of the work. Conscious of the colossal challenge set by the president’s five-year deadline, the Élysée Palace created a special organization to oversee the reconstruction, thereby circumnavigating the culture ministry’s cumbersome red tape, and acknowledged the almost military nature of the task by appointing a retired general to run it, the late Jean-Louis Georgelin (succeeded, after his 2023 death in a hiking accident, by his deputy Philippe Jost). Georgelin found himself commanding what did indeed resemble a small army: 250 contractors employing hundreds of workers, not to mention all the clerical staff needed to process the countless contracts.

Intallation of the timber framework of the nave, choir, and transepts underway in winter 2023. Photo by David Bordes © Rebâtir Notre-Dame of Paris

So far, $740 million has been spent on restoring the cathedral, leaving another $148 million in the donation pot to continue work on the exterior, particularly the bravura, 50-foot-span east-end flyers, which need urgent attention after decades of neglect. Moreover, the city of Paris is spending a further $53 million to reconfigure the spaces around Notre-Dame, a project led by the Belgian landscape architect Bas Smets and set to complete in 2028.

In March 2024, carpenters and other workers celebrated the completion of the nave framework. Photo by David Bordes © Rebâtir Notre-Dame from Paris

On the other hand, the future of the Musée de l’Œuvre is now in doubt. A key part of Macron’s plans, it was scheduled to take up residence next door to the cathedral in part of the Hôtel-Dieu, a hospital whose history is intimately linked to its neighbor’s. Conceived as a home for all the objects and exhibits for which there is no room in the cathedral itself, the museum was also supposed to take a certain amount of tourist pressure off the monument, which was by far France’s most visited building before the fire, attracting 12 million people in 2018. Work was scheduled to begin in 2026 for inauguration in 2028, but so far the design competition has not even been held; now, in the context of France’s record deficit, many wonder if the cash will ever be found for the museum. On the night of April 16, 2019, Macron promised that Notre-Dame would be “rebuilt … more beautiful than ever”—he has until spring 2027, when his second and final term in office ends, to ensure that vision can reach full completion.