Studio Gang’s Populus Takes Inspiration from Colorado’s Towering Aspens

Denver

Architects & Firms

Aspens are self-pruning. As they grow taller, the trees shed low branches, leaving behind round dark scars on their otherwise paper-white bark. “I remember looking at them and seeing all these eyes, which makes me sound paranoid,” says Jeanne Gang with a laugh, recalling her fascination with them. “The marks were so human.”

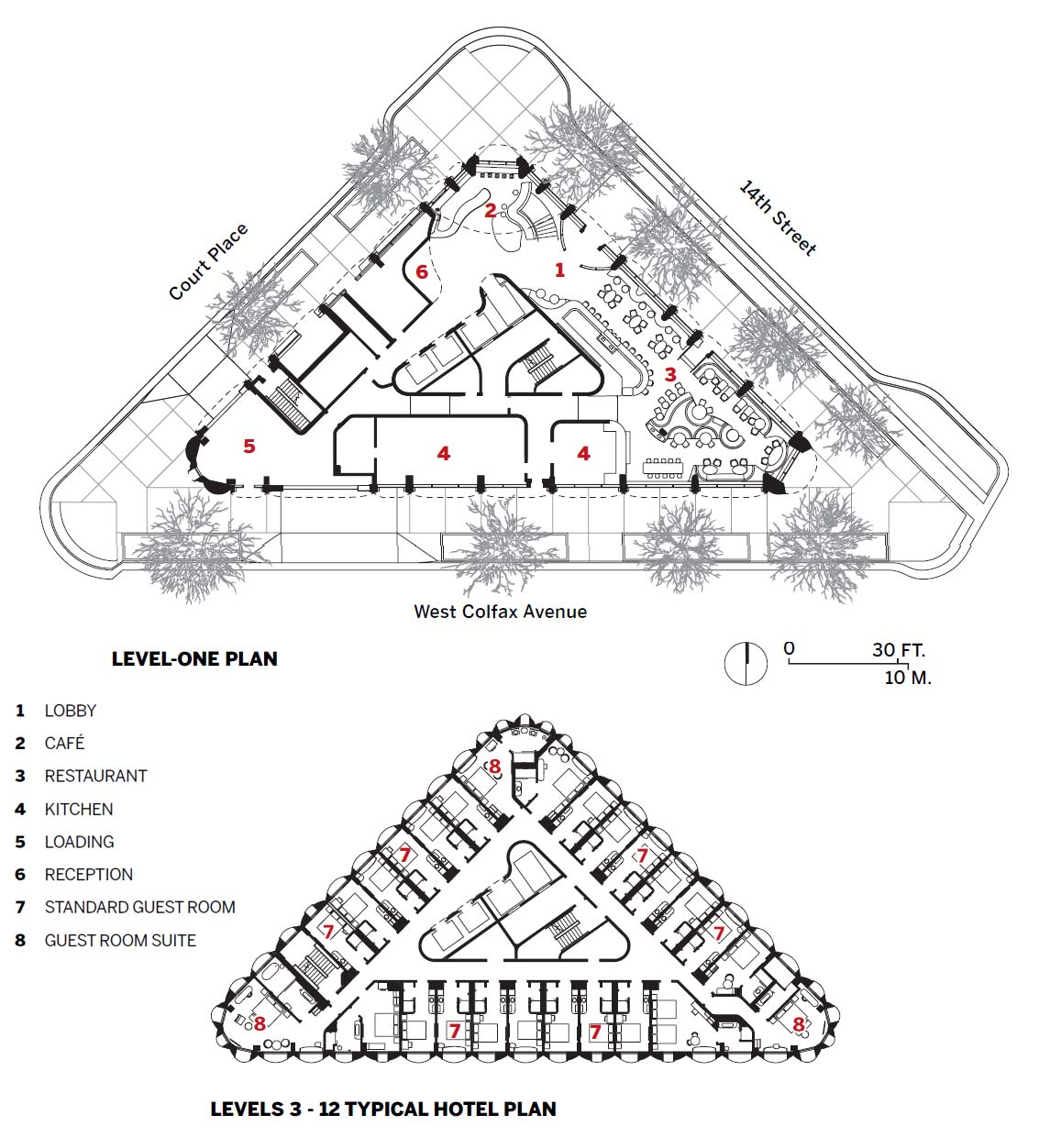

It should come as no surprise then that Populus, a 265-room hotel in downtown Denver, owing a certain design debt to these towering trees, naturally gazes back at the city with “eyes” of its own. (Aspens also provided the name, from Populus tremuloides.) The 13-story high-rise sprouts out of a leftover 9,585-square-foot triangular site near Civic Center Park, in a sleepier part of town lacking after-hours eateries. But Studio Gang and client Urban Villages hope Populus will give visitors and locals alike a reason to hang around—and to feel good about doing so. “We try to operate at the convergence of economic viability and environmental stewardship,” says Jon Buerge, president of the development company.

1

2

Eyelike marks on aspen bark (1) inspired Populus’s ocular windows, shown here in standard rooms (2) and suites (3). Photos courtesy Peng Chen (1), © Steve Hall (2), © Yoshihiro Makino (3), click to enlarge.

3

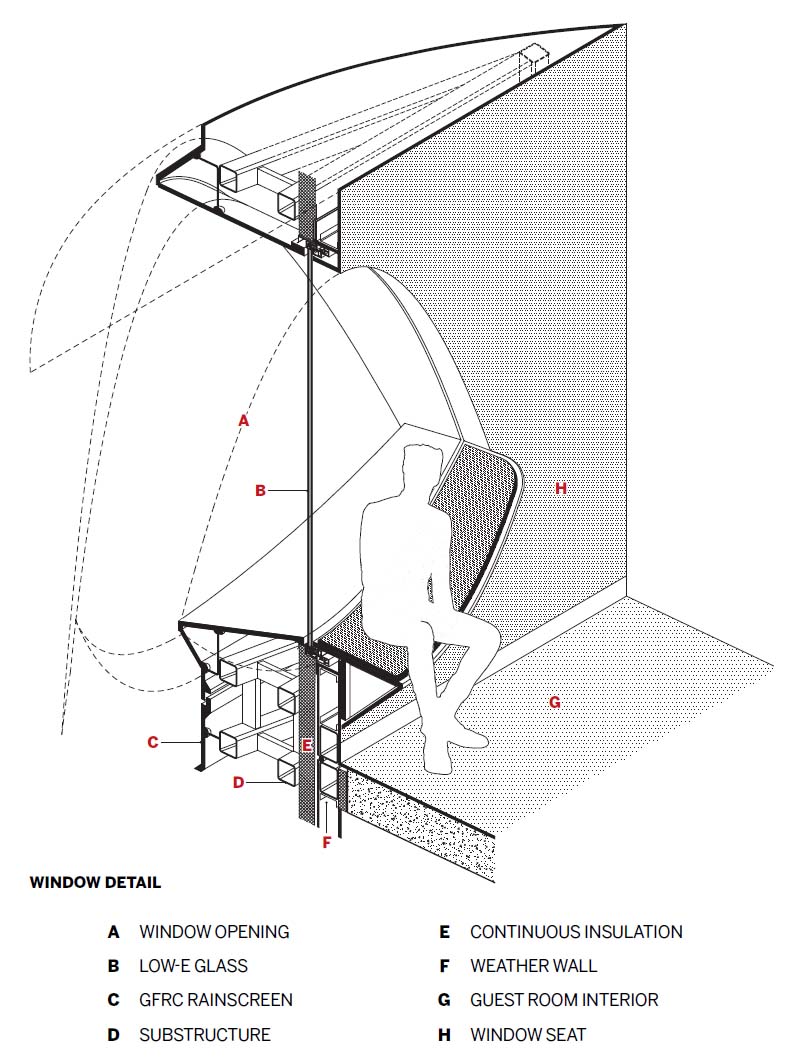

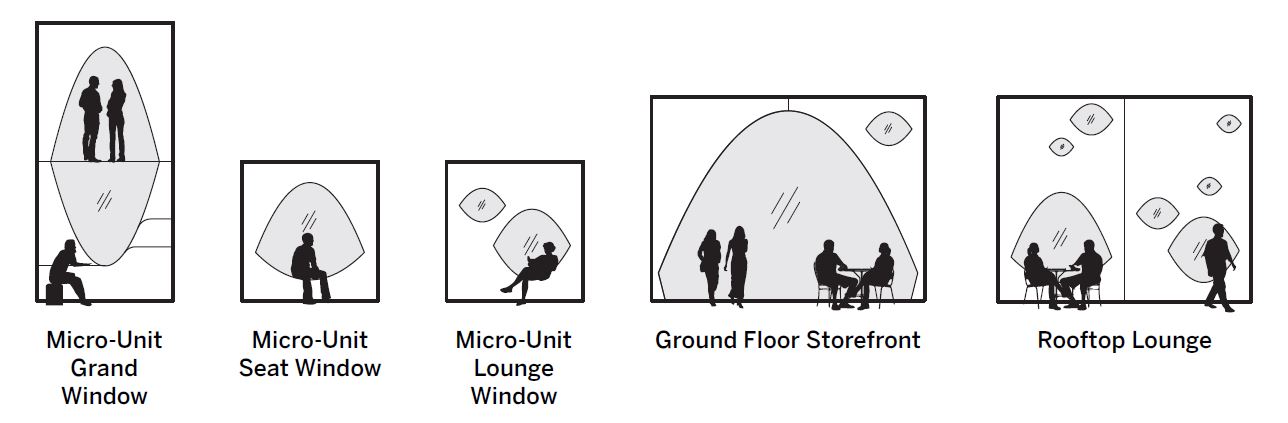

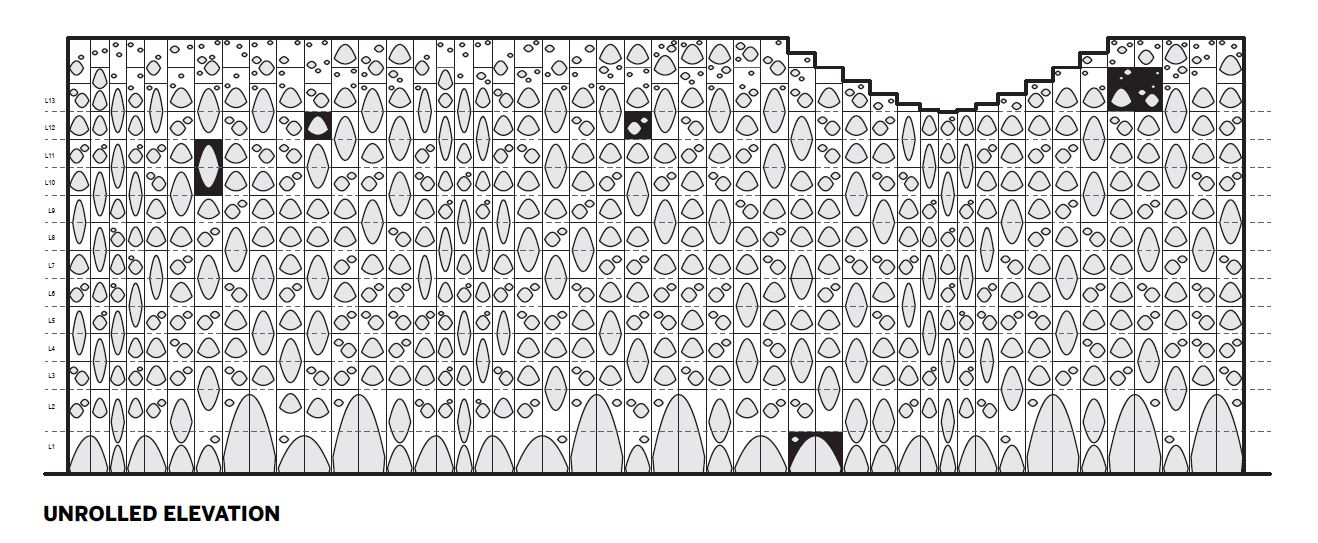

From an architectural standpoint, like Gio Ponti’s nearby addition to the Denver Art Museum, which features eccentric glazing of its own (in the form of slits and elongated hexagons), the hotel takes on an entirely different character, depending on the weather. From afar, on overcast days, it appears as a monolithic prism with stippled fenestration. But Populus really flourishes in full sun, when the daylight animates a scalloped rainscreen with crisp sculptural details, including eyelid-like window surrounds. Although the facade comprises some 400 panels—each made of glass-fiber-reinforced concrete (GFRC) and most spanning a height of two stories—clever repetition made its assembly more economical. The panels’ arrangement in a vertical running bond camouflages identical components (three different panel types account for almost half the envelope) and about 75 percent of the panels share the same radius, allowing the reuse of some molds. Their deep curvature reduces solar heat gain on the building, too. Small flecks of amber- and pewter-toned aggregate, exposed by an acid wash, give the white GFRC radiant warmth.

Sunlight accentuates the rainscreen’s details. Photo © Jason O’Rear

Grand parabolic arches define the street level on all three of its sides, offering passersby glimpses of a restaurant and a café. As part of a broad sustainability strategy, structural floors and walls inside were largely left bare to reduce the need for additional finishes. The task of softening these raw spaces fell to interior design firm Wildman Chalmers, which introduced a palette of earth tones—greens, browns, terra-cottas—as well as textures—tweeds, velvets, leathers. Whenever possible, materials were sourced locally or upcycled: salvaged beetle-kill pine for headboards, reclaimed snow fencing for ceiling slats, and baffles of draped mycelium fabric (evoking a vegan salumeria?) above a bar.

4

5

Reclaimed fencing is used for ceiling slats (4) and mycelium fabric hangs above the lobby bar (5). Photos © Steve Hall (4), Yoshihiro Makino(5)

Upstairs, around a triangular core, 175-square-foot units run the lengths of each facade, while larger suites occupy the rounded corners. Dark finishes in the halls heighten the transition into the much brighter rooms, where Populus’s ocular apertures frame dramatic scenes, urban and natural, near and far. Gang’s team devised integrated seating to play up the openings’ novel shapes. There are plenty of meeting spaces and lounges, and, at the very top, a roof terrace and bar offer elevated views of the State Capitol.

But perhaps most of the hype surrounding Populus, which opened to the public in October, has stemmed from the developer’s claim that it would become “carbon positive”—meaning, according to Urban Villages, the hotel would sequester more carbon in biomass and soil than its combined embodied and operational footprints. Current estimates of the former equal 6,675 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (mTCO2e)—a number that would have been even higher without the project team’s sustainability-minded design decisions and certain variances. For example, Populus is Denver’s first new building without on-site parking, which would have required far more excavation and concrete.

Most of any building’s embodied carbon, however, lies in its structure. Although the project’s designers considered mass timber early on, not all municipalities—Denver included—have embraced the system for high-rises, even if sustainably harvested lumber is locally abundant. “The fire department was not willing to entertain it,” says design principal Juliane Wolf, despite input from outside experts. To reduce the carbon footprint of the concrete slabs ultimately used to span from the core to the perimeter, engineers specified a mix that substituted other cementitious materials, such as fly ash, for a portion of energy-intensive Portland cement.

In the end, Populus is only targeting LEED Gold. Jumping to Platinum represented “a significant price increase,” says Buerge, one that “from our perception, our calculations, felt like only a minor improvement.” Instead, those extra dollars were spent on carbon offsets. The developer has, so far, purchased 7,000 mTCO2e-worth of certified forest and soil carbon credits from U.S.-based projects. This includes a reforestation effort, in partnership with the U.S. Forest Service, which aims to plant 172 acres of trees to repopulate areas of Colorado devastated by beetles. To offset operational carbon, Populus will continue funding such forestry projects into the future, reduce food waste sent to landfills, and source 100 percent of its power from renewables. “You do what you can with what you have,” Gang says, reminding us that effecting incremental change is better than none at all.

Aspens, among other biological quirks, spread via rhizomatic networks—what might seem like a forest of individual trees may be in fact a single organism. Is Populus the first of more to come? If, with time, the hotel sustains its energy goals and enlivens the downtown scene, we could even see another (or two) cropping up elsewhere in the country.

Click plans to enlarge

Click detail to enlarge

Click graphic to enlarge

Click elevation to enlarge

Credits

Architect:

Studio Gang — Jeanne Gang, lead designer; Juliane Wolf, William Emmick, principals; Kristina Eldrenkamp, project leader; John Dolci, Ensonn Morris Jr, Lindsey Krug, Noora Aljabi, Cassie Dickson, Shovan Shah, David Swain, Jason Flores, Bella Adekoya, project team

Engineers:

Studio NYL (structural and facade); WSP (sustainability); CMTA (m/e/p); Kimley-Horn (civil)

Interiors:

Wildman Chalmers (design); Fowler (interior architecture)

Consultants:

Superbloom (landscape); LS Group (lighting); Lerch Bates (vertical transport); Pique Technologies (AV/IT); Next Step Design (food service); Advanced Consulting Engineers (code)

General Contractor:

Beck Group

Client:

Urban Villages

Size:

135,000 square feet

Cost:

Withheld

Completion Date:

October 2024

Sources

Structure:

Holcim (concrete); Keller, RK Steel

Cladding:

Unlimited Designs (GFRC); Gen3 Construction (slab edge panels); Morin (standing-seam panels); Kawneer (curtain wall); Sto Corp (EIFS); 3A Composites (ACM); GE (moisture barrier)

Roofing:

Carlisle SynTec Systems (EPDM); Hydrotech (pavers)

Windows & Doors:

Solar Innovations, 8G Solutions, VT Industries, LaForce, O’Keefe Millwork, Raw Creative

Lighting:

Lumenture, Nora, DMF, Flexalighting, H.E. Williams, Lutron

Interior Finishes:

Daltile, Trend, M Stone, Ann Sacks, TileBar, Bedrosians, Clé, Porcelanosa (tile and stone); Rocky Mountain Hardware, Assa Abloy, VingCard (hardware); Tadelakt, USG (special surfacing); Sherwin-Williams (paints); Formica, Fenix (laminate); Keilhauer (reception furniture); ASL Stone (entry pavers)