“No national park,” the yard signs said. “Give Maine Back to Mainers.”

This was nearly a decade ago, amid opposition to philanthropist and Burt’s Bees cofounder Roxanne Quimby’s plan to donate 87,563 acres in northern Maine to the National Park Service (NPS). The ardent conservationist came head-to-head with the state’s legacy of private land ownership, with many wary of the possibility that the federal government would restrict hunting, fishing, and other recreational activities.

To Quimby’s son, Lucas St. Clair, an outdoorsman who grew up here and later joined her campaign, the argument wasn’t just about conservation. It was also about rural economic development—attracting visitors and bringing back jobs to a region once home to the country’s largest paper mills. “Her acquisition of the land represented the fact that those mills weren’t returning, in a really visceral way,” St. Clair says. He listened to concerns and, slowly, he began to persuade skeptics.

Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument was ultimately established by presidential proclamation in 2016. St. Clair’s Elliotsville Foundation kicked off development of trail and camping infrastructure for NPS while also setting its sights on something more ambitious—a visitor contact station. Many of the country’s great national parks benefit from identifiable architectural landmarks: the arts-and-crafts Old Faithful Inn in Yellowstone and Glacier Park Lodge in Montana, for example. But what should such a structure—one with the benefit of our current understanding of environmental stewardship—look like in the 21st century? In architect Todd Saunders, Quimby and St. Clair found a fellow naturalist, whose Fogo Island Inn had set out to achieve similar goals in Newfoundland.

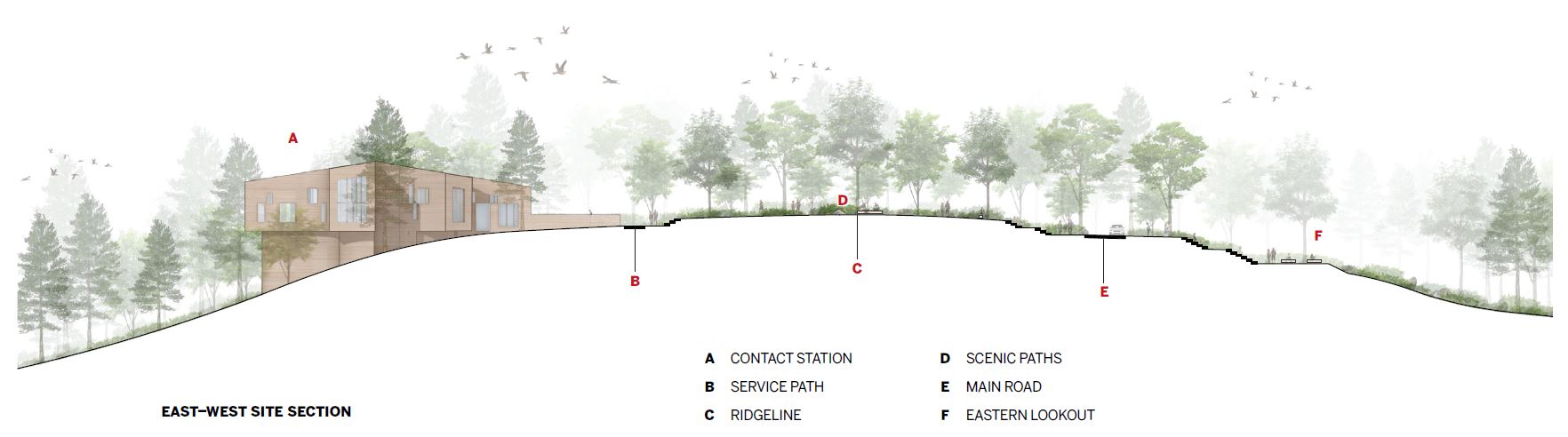

Accessing the spectacular site identified by St. Clair requires a 30-minute scenic drive through rural towns and woodlands from I-95. After reaching the parking area, visitors ascend on foot to the ridgeline, where the Tekαkαpimək Contact Station slowly comes into view through a stand of young yellow birches. Ground-covering ferns define the edges of meandering pathways that thread through them. This is second-growth forest, explains John Grove, principal of Reed Hilderbrand, the landscape architect—the ridge and surrounding area have been logged a few times over the last century. Beyond the trees, down a set of granite stairs, the contact station reaches to the west, toward Mount Katahdin, the state’s tallest peak.

Paths of locally quarried granite lead to the station. Photo © James Florio, click to enlarge.

Unlike a visitor center, usually located at the edge of a park, a contact station sits deep within one, serving to orient visitors to nearby topography, trails, and waterways. More practically, they are restroom pit stops and places to refill a water bottle or collect a park passport stamp. From its perched placement, this contact station offers quite the vantage point—Tekαkαpimək, after all, is Penobscot for as far as one can see. But the orientation is not just spatial. It’s also cultural.

St. Clair, aware of the significance of these lands to Indigenous people, invited a board comprising members appointed by the chiefs of the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians, Mi’kmaq Nation, Passamaquoddy Tribe, and Penobscot Nation—together known as the people of the dawnland or the Wabanaki—to advise on the design of the station from the beginning. But he and Saunders were not expecting such strong opposition to the initial concept, which echoed the colonial vernacular of New England farmhouses and schools. Overlooking a sacred landmark like Mount Katahdin, a structure in this style prompted painful memories of forced assimilation only a few generations ago. “It added tremendous pressure,” St. Clair recalls, “but, if we didn’t go through this process, we weren’t going to have anything worth building.”

Planks of cedar form horizontal bands along the facade. Photo © James Florio

Some architects might have balked at the feedback, or walked away entirely. “I’m used to being an outsider,” says Saunders, whose practice is in Norway, far from the Canadian Maritimes where he grew up. “I can’t speak to their firsthand experience, but I knew I needed to ask a lot of questions and listen.” His team began drafting a scheme with input from the advisory board, which introduced Saunders to ideas derived from the curvilinear form language of Wabanaki building traditions and artwork. He had been particularly struck by a visit to a domed wigwam, with its exposed structural ribs, tied together by spruce roots and sheathed in rows of birchbark—details that were loosely reimagined in the final design.

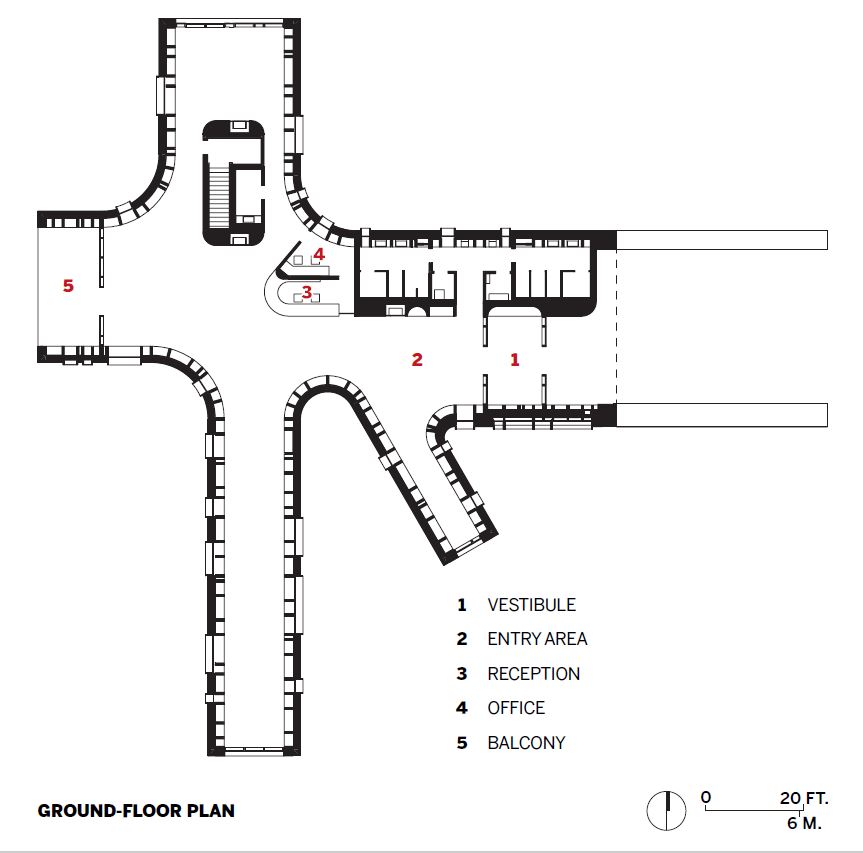

As built, the station features a plan of intersecting wings, each cantilevering into the tree canopy and gently curving from one to the other where they meet. Rough-sawn planks, arranged in a series of overlapping bands of graduated heights—from about 1 foot at the bottom to 6 feet at the top—create strong horizontal shadow lines that emphasize the station’s sinuous elements. Even though this cedar cladding has already started to take on a silvery patina, its pleasant aroma still lingers heavily in the air. Thick-framed windows in abstract groupings punch through the facade.

Each wing juts into the surrounding foliage. Photo © James Florio

Collaborative efforts extend inside. Bronze pulls on the entry doors feature four “double curves,” or stylized glyphs—each designed by James Eric Francis, Sr., who is Penobscot, in consultation with the respective tribes of the Wabanaki Advisory Board. From the central reception area, park-goers can wander down any of the wings, whose axes have been shifted to obfuscate views and invite exploration. “To the Wabanaki, there’s significance to the cardinal directions,” Saunders explains. “But, rather than have a simple cross, I wanted to break predictable geometry.”

In place of cedar, Douglas fir boards line the interior walls and ceiling overhead. “The material palettes in my projects are simple. I grew up with salt, pepper, and dill as spices—that’s it,” Saunders says with a laugh. But even in Maine, the most forested state in the country, certain arboreal species are endangered. Above the reception desk, an undulant woven ceiling and wall, made by a group of Indigenous artists from bands of oxidized and polished copper, serves as a potent, if alluring, reminder of increasing scarcity. Not only does it signify the importance of weaving to the Wabanaki, it also acknowledges the proliferation of the emerald ash borer, which has decimated the trees still used in their basketry.

A balcony offers panoramic views. Photo © James Florio

Wood also fuels the most visible source of energy for the off-the-grid, near net zero structure. Three working fireplaces, each marked by tall panels that emulate Indigenous birchbark etchings, heighten the interior’s sense of warmth, figuratively and literally. They are supplemented by a more discreet heat pump and radiant-floor system, powered primarily by a nearby photovoltaic array. (A gas-fired boiler kicks in when the PV batteries dip below 20 percent.) Passive strategies—a Trombe wall for thermal mass and a night-flush system for cooling—help too.

The station’s structural perimeter walls comprise exposed glue-laminated timber columns with an interesting edge detail—always four boards abreast, sometimes with one or both middle pieces inset. Also adding to the visual rhythm: the insertion of extra columns, creating deep niches of varied widths that accommodate exhibition materials, seating, artworks, or window openings. All 159 of these glulams were fabricated in a nearby potato barn by general contractor Wright-Ryan, using local dimensional lumber. They were also subjected to shear and delamination tests at the University of Maine’s Orono campus. The land, from a building-code standpoint, is considered “unorganized territory,” explains architect of record Ed Parker, of Alisberg Parker. “A lot of what we did was self-certified, because no municipality oversees this area.”

1

Exhibitions are integrated into wall niches made of Douglas fir (1 & 2). Photos © James Florio

2

Notably, the exhibitions do not paper over the architecture; they are integrated within it, allowing the walls to speak, and with new voices. “Indigenous people here in Maine have grown up going to parks and museums to see ourselves in a sentence that usually begins ‘12,000 years ago’—and then it stops,” says Jennifer Neptune, who developed the curatorial framework and comes from a family of Penobscot guides. “It’s rare that we can tell the story through our own worldview. We’re in the places where these stories originated and have been told for thousands of years, passing from family to family.” Significantly, NPS signed a first-of-its-kind agreement protecting all Indigenous culture and knowledge within the station.

3

A lookout (3) and the station form an east–west axis along the site (4), where collaborators often met (5). Photos © James Florio (3 & 4), Landyn Francis, Penobscot (5)

4

5

Texts and visuals have been printed directly onto bent-plywood panels, which nestle into the wall niches alongside interactive elements and works by Indigenous artists. These displays, designed by WeShouldDoItAll, range from instructions to canoeists about reading the waters’ eddies and riffles to overviews of local fauna, such as the Atlantic salmon that return to the Penobscot River, just down the ridge, to spawn. Most insightful are the didactic pairings of Western and Indigenous narratives about glacial erosion and the movement of the stars in the night sky. But what unifies them lies underfoot—floor tiles have been laser-etched to depict the watershed, highlighting portage routes that connect the four tribal communities.

There is an old park adage about being prepared, but also arriving with the right attitude: there’s no such thing as bad weather, only bad gear. Today, many have changed their minds about the monument, and the station provides yet another reason to visit. The endeavor has also lived up to its promise of economic development, for Mainers and tribal citizens alike. The Elliotsville Foundation estimates some 80 percent of expenditures for the building have gone directly to the surrounding region, with as much as $2.8 million being brought to the area by about 40,000 park-goers annually. But, most important, St. Clair and others wanted visitors to show up with a willingness to learn—and now they have a means to do so.

Click plan to enlarge

Click elevation to enlarge

Credits

Architect:

Saunders Architecture — Todd Saunders, Ryan Jorgensen, Éva Baráth

Architect of Record:

Alisberg Parker — Ed Parker, Shaun Gotterbarn

Engineers:

Atelier One (structural); Haley Ward (civil, surveyor); Salas O’Brien (m/e/p)

Consultants:

Wabanaki Advisory Board (project and exhibits); Reed Hilderbrand (landscape); Transsolar (energy); JQP (accessibility); Tūhura Communications, Jennifer Neptune (interpretive plan); WeShouldDoItAll (exhibits/signage); Split Rock Studios (exhibition fabrication); Jane Anderson (ICIP); Erin Hutton Projects (creative program management); Stern Consulting (project management)

Wabanaki Advisory Board:

Natalie Dana-Lolar, Passamaquoddy/ Penobscot; John Dennis, Mi’kmaq; James Eric Francis, Sr., Penobscot; Nick Francis, Penobscot; Gabriel Frey, Passamaquoddy; Jennifer Gaenzle, for Mi’kmaq; Suzanne Greenlaw, Maliseet; Newell Lewey, Passamaquoddy; Jennifer Neptune, Penobscot; Kendyl Reis, for Mi’kmaq; Richard Silliboy, Mi’kmaq; Donald Soctomah, Passamaquoddy; Chris Sockalexis, Penobscot; Isaac St. John, Maliseet; Susan Young, for Maliseet

General Contractor:

Wright-Ryan Construction

Sitework:

Emery Lee & Sons, OBP Trailworks

Client:

Elliotsville Foundation

Owner:

National Park Service

Size:

7,895 square feet

Cost:

$31 million (total)

Completion Date:

August 2024

Sources

Structure:

Nordic Structures (CLT floor slabs); Unalam (glulam); LMC Light Iron (steel); Mainely Trusses

Cladding:

Dewey’s Lumber and Cedar Mill, Hammond Lumber; Henry, 3M (moisture barriers)

Roofing:

Sheffield Metals International, Murus, GCP

Windows & Doors:

Duratherm, Curries, VT Industries

Lighting:

Lumenwerx, Feelux, Ledra, Lithonia, Cooper

Glazing:

Agnora, Saint-Gobain

Interior Finishes:

Windham Millwork (cabinetry); Von Duprin, Dormakaba, FSB, Sargent, LCN (hardware); C2 (paint)