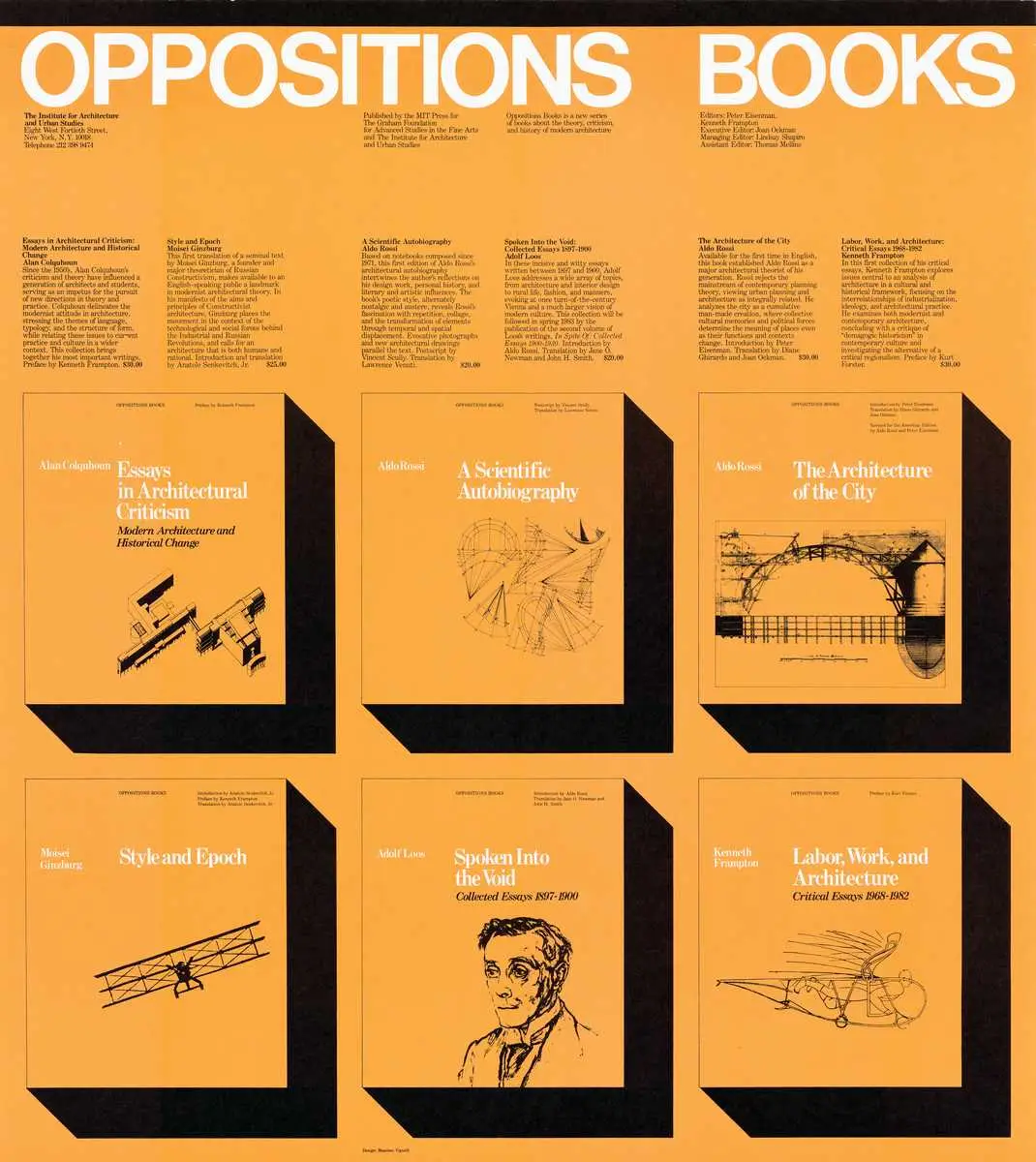

Weighing in at 3 pounds, more than 2 inches thick, and a whopping 584 pages, Kim Förster’s new book, Building Institution, contends with the Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies (IAUS) and the roster of architectural heavyweights it produced. Founded in 1967 in New York by Peter Eisenman, the Institute hosted many notable figures who were fellows or visiting fellows (to say nothing of its many students or collaborators), including Emilio Ambasz, Deborah Berke, Kenneth Frampton, Arata Isozaki, Rem Koolhaas, Aldo Rossi, and Bernard Tschumi. In the 18 years it was active, in addition to projects, exhibitions, and lectures, the Institute produced numerous publications that have had an enduring impact on architectural discourse, notably, the theory journal Oppositions, the Oppositions Books series, the newspaper Skyline, and the art journal October, which outlived the Institute and is still being published. Following this paper trail of cultural production to discover what it says about the “institutionalism” of the IAUS is Förster’s primary focus.

A circa-1981 poster, by Italian graphic designer Massimo Vignelli, for six titles in the Oppositions Books series produced by the IAUS. Image © Vignelli Center for Design Studies, RIT, click to enlarge.

This tome is the product of 18 years of work that started with Förster’s doctoral research at ETH Zurich. This dissertation-cum-book—what Förster describes as a “genealogical-archaeological narrative”—does read like a dissertation. Not exactly bedtime fare or a beach read, Building Institution is deeply concerned with its own position vis à vis existing literature and future scholarship, with meticulous noting of the intellectual concepts it invokes, and with its own methodological rigor (indeed, Förster devotes nearly eight pages of his introduction to outlining the book’s historiography and structure). The book draws on more than 100 interviews gathered by the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), where Förster was an associate director from 2016 to 2018 and where the Eisenman fonds is located, and on research Förster conducted in archives at the CCA, MoMA, Columbia University, Princeton, the Beinecke Library at Yale, the Getty Research Institute, Rochester Institute of Technology, the AIA—even the IRS. In short, Förster has done the exhaustive scholarly work to produce what should be considered the definitive history of this important institution.

Förster is also deeply concerned with inherited narratives. His aim is to demythologize the Institute, which, he explains, has been viewed as something of a “scene,” in the 1970s sense, or a Postmodern Bauhaus with Eisenman cast as Walter Gropius, or a think tank that functioned as an alternative to academia and produced a new generation of avant-gardists. Unlike the oral histories, essays, and a documentary film that have thus far told the Institute’s story and helped shape this “mythology,” all of which were produced by former fellows, Building Institution is the first comprehensive history written by someone completely unaffiliated with it.

Through his in-depth archival research, Förster investigates how the Institute became an “institution” and how it helped shape, and was shaped by, the paradigmatic shift from Modernism to Postmodernism. The book is broken into four chapters that focus on different aspects of the IAUS’s formation, from how it legitimized and positioned itself among other established East Coast institutions, such as MoMA and various Ivy League universities, to how its educational programming as well as the circulation of its printed matter exerted influence over both architectural practice and academia.

The unmatched value of Building Institution is that it is a serious history—arguably the first such history of the Institute. But perhaps the seriousness of this book is also at times its blind spot. The sober reading sometimes misses the irony associated with these icons of Postmodernism. A footnote in Förster’s introduction is instructive: “Eisenman, with his characteristic subtlety, repeatedly referred to the Institute as a ‘halfway house’ because of the position it took between academia and architectural practice, thus adding another provocative meaning to the Institute with this play on words; in American, ‘halfway house’ colloquially stands for an open psychiatric ward or rehabilitation clinic.” Förster’s wonkish interpretation seems precisely backward. The self-deprecating joke is not subtle but primary. Another example is his discussion of the Institute’s first logo, Cesare Cesariano’s 1521 Vitruvian Man with an erection. Förster theorizes this choice as an exercise in branding, invoking Le Corbusier’s Modulor and Susan Sontag’s “Notes on Camp.” But maybe it was selected because it’s humorous.

In Förster’s telling, the IAUS comes across as an ambitious group that “planned to capture architectural discourse, create networks, and exploit synergies, i.e., to redesign architecture in general,” with Eisenman as its strategic, entrepreneurial, and almost Machiavellian leader. Instead, could the Institute be seen as a group of wayward souls, armed with wits and wit—a 35-year-old Eisenman having been denied a tenure-track position at Princeton and in need of a new gig, for example—navigating through the unknown during the uncertain times of the late ’60s and ’70s? In the attempt to understand the formation and operation of an institution by delving into its archival records, has Förster inadvertently replaced one mythology of the Institute and of Eisenman with another? The truth probably lies somewhere in between. To his credit, in Building Institution, Förster has meticulously, generously, and commendably supplied the detailed information for attentive readers to draw their own conclusions.