You might call it a shotgun wedding, or a strategic partnership. “We basically had five days to put the submittal together,” recalls HDR principal Tom Trenolone of teaming up with NADAAA to design the CoARCH Pavilion at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s (UNL) College of Architecture. “I reached out to Nader and said, ‘You don’t know who I am, you’ve never met me before, but I think we’d make a great team.’” The mega-sized HDR, headquartered less than an hour’s drive from UNL in Omaha, was the local heavyweight, and Trenolone a fixture of the UNL architecture faculty. Tapping into NADAAA, led by Nader Tehrani, Trenolone was aware that the small Boston-based firm had won an earlier commission to design the annex several years before, a project that had subsequently been canceled. NADAAA had also completed three other schools of architecture. Significantly, both firms had previously built with mass timber, a requirement of the brief—NADAAA at a dormitory at RISD, the Rhode Island School of Design, and HDR with two other buildings in Nebraska but close to 50 across its international portfolio.

1

2

The dark four-story addition with its exposed-wood base is a sharp contrast to its redbrick neighbors (1, 2, and top of page). Photos © Nic Lehoux, click to enlarge.

Speed, of course, remained the name of the game throughout the design and construction process, which started with that first phone call in late April 2022 and culminated just over two years later with the inauguration of the 21,000-square-foot building in September 2024.

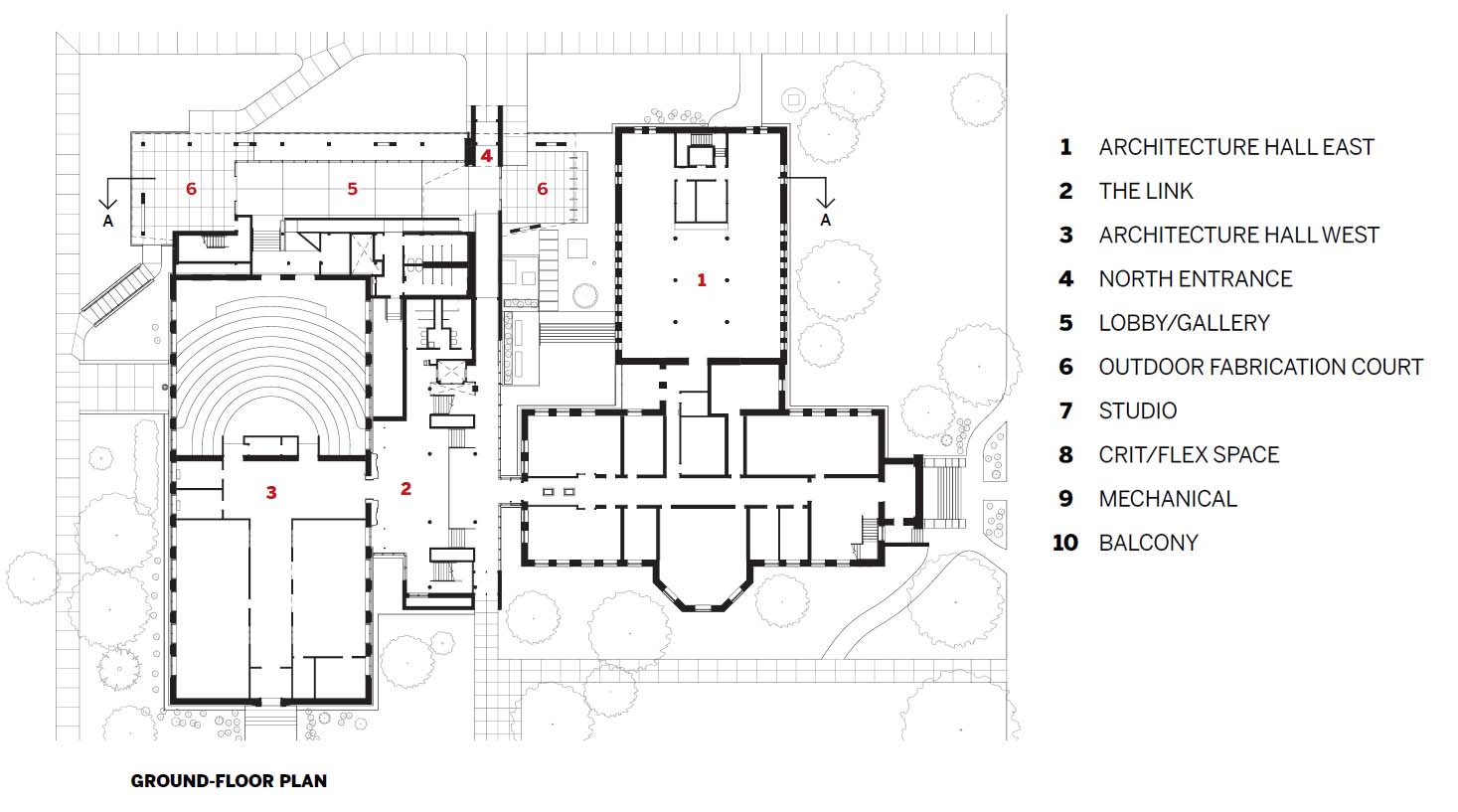

The resulting four-story rectangular structure is a simple one, with three levels of open studio space stacked over the ground-floor lobby/gallery, but its location is special. CoARCH sits beside the redbrick, hip-roofed, T-shaped Architecture Hall (1895), the only building still standing on UNL’s City Campus that reminds visitors of the university’s Victorian-era beginnings (whose south wing comprises a heavy timber structural system) and is a stone’s throw from the present-day Big Ten school’s nearly 90,000-capacity Memorial Stadium to the north and the Sheldon Museum of Art to the east. So, while it may be a “dumb warehouse”—as the designers originally referred to it—the building needed to make some very clever moves, which it did.

3

The interstitial space between Architecture Hall West and the new addition offers areas for crits. Photo © Nic Lehoux

A 1980s renovation by Nebraska firm Bahr, Vermeer, and Haecker, dubbed The Link, connected the 1895 building to what had been the law college just west of it (now known as Architecture Hall West). The Link’s glass atrium contains stairs and an elevator for the complex, which also included an addition to the north of the law school that had been built as the law library but was later converted to architecture studios. “The difficulty was that all the studios were staggered, using the old book stacks,” says Trenolone. “There was a single elevator in the middle and a central-core stair that went through the studios. The acoustics were terrible, and accessibility was a problem.”

3

The third-level studio steps down to a flexible space that can also be used for reviews. Photo © Nic Lehoux

This new addition takes the place of that problematic one, making its floor slabs level with those of its neighbors, and eliminating the need for additional elevators. A key logistical difficulty—namely, accessibility—was thus solved, but the design team made further use of the infrastructure of the other buildings: new bathrooms were backed up to existing facilities to centralize plumbing, and the basin of the razed building was used for mechanical spaces.

The architects then turned their attention to articulating the hybrid structure (there is steel in parts) and came up with a striking solution that makes this cross-laminated timber (CLT) and glulam building stand apart from most others. Inspired by RISD’s sculpture building on North Main Street in Providence—a brick shed with one facade composed entirely of Kalwall, that insulated, light-transmitting panel—Tehrani, with costs in mind, proposed using the decades-old product for the long north elevation. “Considering the time necessary to install a stud wall, insulation, waterproofing, vapor barrier, the inner gyp board, and then the cladding, plus all the different trades involved with those,” explains Tehrani, “it made more sense to go with a ‘one system fits all’ strategy.”

3

Translucent Kalwall panels clad the long north elevation (3), while floor-to-ceiling glass on the shorter facades and within the slit windows between the Kalwall allows views out (4). Photos © Nic Lehoux

4

And, like timber, Kalwall had its precedent at the school, in a pair of prominent skylights. Though the structural sandwich panel is generally used in applications such as that, it has also graced more “elevated” projects, including Edward Durell Stone’s U.S. Pavilion for the 1958 World’s Fair. What’s striking at UNL is the multidirectional, splayed running bond arrangement of the panels on the upper three levels. The angled 12-by-17-foot Kalwall sections open up to 2-foot-wide, full-height windows allowing east-facing views from the studios to the museum, and west where throngs of Cornhusker fans pour in along the stadium promenade on game day. At the ground level, which includes an open fabrication court behind hefty, exposed-wood columns and diagonal bracing, a black protruding element—matching the dark upper floors—offers a front entrance along that north elevation, something the earlier building lacked.

3

The north facade provides glimpses of what’s inside when lit up at night. Photo © Nic Lehoux

While providing views to campus icons was a goal of the facade arrangement, the facade itself offers quite the view. For an architecture-school building, where students will probably toil long into the night, CoARCH’s backlit, translucent skin reveals not only the structure within, but the dedication of those students hoping to one day design such a building of their own.

Click plan to enlarge

Click plan to enlarge

Click section to enlarge

Credits

Architects:

NADAAA and HDR Great Plains Studio(s)

Engineer:

HDR (civil, structural, m/e/p)

Consultants:

Timberlyne Wood Solutions

General Contractor:

Whiting-Turner

Client:

University of Nebraska–Lincoln, College of Architecture

Size:

21,200 square feet

Cost:

$23.2 million (total); $20.6 million (construction)

Completion Date:

September 2024

Sources

CLt and Glulam:

Timberlyne

Resilient Flooring:

Johnsonite/Tarkett

Curtain Wall:

Kawneer

Roof Decking:

Nucor

Metal Framing:

ClarkDietrich

Lighting:

USAI Lighting, Litelab, Lumenpulse

Hardware:

Assa Abloy