Centerbrook Architects’ New Canaan Library Ushers a Civic Anchor Into the 21st Century

For more than a century, New Canaan’s public library has been a centerpiece of the bucolic—and affluent—western Connecticut town. Originally built in 1913, the library building was bordered by downtown’s Main and Cherry Streets and saw three major expansions, the last of which was in 1979. Called to respond to the changing needs of New Canaan and the modern media landscape, in which some physical books can be replaced by digital assets and make way for other forms of programming, the library undertook a major fundraising campaign to construct an entirely new building on the same site.

“What we were hoping for was a community hub, a place for gathering and social interaction, and stretching people’s definitions of what libraries are,” says Ellen Crovatto, CEO of New Canaan Library. She adds that libraries have moved away from being places where people are shushed for talking, to spaces that are “active and loud and communal.”

Inside the main entrance of the new New Canaan Library. Photo © Jeff Golberg/Esto

The library replaces a similar-sized building but increases usable space by 30 percent while using less energy. Since the new building’s opening in February 2023, the library has seen a 70 percent increase in visitors and 250 percent increase in programs. Photo © Jeff Goldberg/Esto

When the library approached Connecticut-based Centerbrook Architects to design its new building more than a decade ago, principal-in-charge Jim Childress came to the project having worked on several libraries. The New Canaan project further revealed his lifelong affection for these institutions—Crovatto describes Childress as a “professional library tourist.” (He is also an avid volunteer at his local branch in the town of Essex.) “That sensibility permeates the thoughtfulness and intent behind every decision that was made here in the design,” says Crovatto. “He has a world view, an interest in what is happening in Scandinavia, Amsterdam, Japan, and South America.”

To that end, the 42,700-square-foot library’s entire first floor fosters community (and, yes, a little noise). The primary Maple Street entrance opens into a grand concourse with a café, rotating gallery space, and open displays for contemporary titles of interest. A north-facing terrace hosts events and outdoor lunches, and a teaching kitchen makes community classes and even visits from celebrity chefs possible. A pocketed dividing wall opens to join the kitchen with a double-height, 350-seat performance and lecture hall, serving the library’s goal of providing near-daily community programming.

The second floor is a more work-focused space, with coworking-style desks and private meeting rooms as well as a dedicated teen library that gives students a welcoming place to study. This floor also has a rooftop terrace overlooking the library green that can also be used for special events. Photo © Jeff Goldberg/Esto

Located on the ground-floor, the children’s area features special seating and an eclosed garden. Photos © Jeff Goldberg/Esto

The ground-floor children’s room is an important point of first contact for many new families. Set behind a glass interior wall just past the library’s main entry, the two-story, 9,000-square-foot space has kid-friendly shelving and seating, as well as three program rooms and an enclosed courtyard garden. A low space created by the mezzanine level overhead became a special “Tween Cave” that is visually open, yet separate. Behind a door, library staff have their own offices and workrooms.

The building’s Energy Use Intensity (EUI) is 17, which is 89 percent lower than the baseline EUI for libraries in this climate. Photo © Jeff Goldberg/Esto

.webp)

The new library is located adjacent to the 1913 Legacy Building, which housed the original New Canaan Library. Photo © Jeff Goldberg/Esto

Though the library itself is only slightly larger than the previous building, the grounds of the nearly 2.5-acre site were made possible by some Tetris-esque maneuvers in the early phases, which involved acquiring most of the full-block site (save for an active gas station at the northwest corner) around the original footprint for construction. Much of the previous complex was demolished, with the exception of the original 1913 library by architect Alfred H. Taylor. Referred to contemporarily as the Legacy Building, it was carefully moved about 100 feet to its right on rails to sit across a courtyard from the new library and will likely reopen to the public as a rentable meeting space when budget allows for its renovation. Now, that colonial-style building with fieldstone walls borders the western edge of a gently graded, nearly one-acre community green designed by landscape architecture studio Stimson, who included bioswales to mitigate strain on the town’s already-taxed stormwater drainage system. Centerbrook chose thin-cut Connecticut fieldstone to clad the new building’s exterior, tying in the Legacy Building and maintaining its commitment to local materials when possible.

Birch and hickory, two tree species native to the region, are used in the library’s millwork. The veneer is from Forest Stewardship Council—controlled sources and panels are produced without formaldehyde. The rotary-cut figured grain produces the least waste in its manufacturing process. Photos © Jeff Golberg/Esto

The mezzanine-level fireplace (seen at far left) uses LED lights projected onto a small amount of water vapor to give the effect of a cozy fire while using only a small amount of energy. Photo © Jeff Goldberg/Esto

Having learned from libraries around the world, Childress’ team emphasized visual connection throughout. “We focused on the idea of giving everybody their own little place to be, but also allowing them to be able to see everybody else,” he says. Open sightlines allow librarians to keep an eye on field-trip groups and activity on other floors even while working at their desks, which were custom-designed by Centerbrook along with millwork display shelving.

Newspaper readers may seek the library’s mezzanine level, known as the living room, with plush seating and a vapor fireplace (which uses LEDs projected onto water vapor); a maker space is separated by a wall of glass making its lively activity acoustically, but not visually, separated. Overhead, a crenulated ceiling helps reflect and diffuse light from skylights, and also conceals the building’s heat pump system, which allows the building to function entirely on electric energy. Childress explains that though the library couldn’t afford LEED certification, “our specialty is working with people who can’t afford that. We’ve worked that checklist into our design process, so that all our energy modeling was more robust than what you’d normally do.”

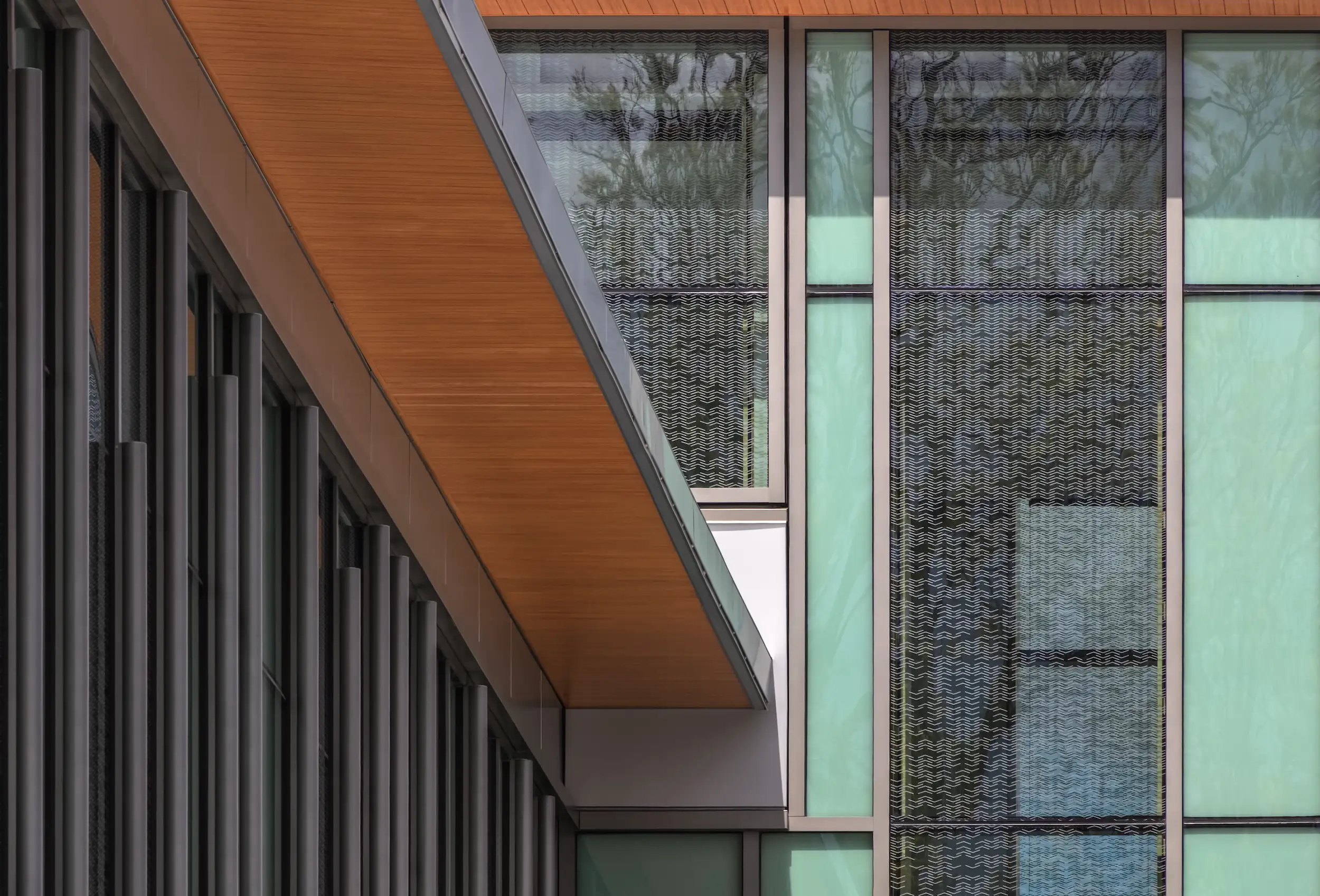

The American Bird Conservancy estimates that a billion birds die from building collisions every year in the U.S. The bird/book patter on the library’s glass is a custom-designed frit that deters birds from flying into its expansive windows. It also cuts down on glare and heat gain. Photos © Jeff Goldberg/Esto

In addition to its central location in town, the library is at the heart of another part of New Canaan’s fabric: the Design for Freedom (DFF) movement initiated by the nearby cultural and humanitarian center Grace Farms. As a pilot project for DFF, which aims to eliminate forced labor in the built environment, the design team and project contractor Turner Construction tracked the origins of key material components including wood, stone, and soft furnishings. “It really started our thinking in that realm, and now it’s worked into our specifications so it will start having an impact,” says Childress. With suppliers increasingly understanding that architects and institutions are expecting social responsibility from material manufacturers, the library is having a positive civic effect on its town and the broader world in more ways than one.

Photo © Jeff Golberg/Esto

Click site plan to enlarge; courtesy Centerbrook Architects and Stimson