Embedded Pre-K classrooms aren’t unprecedented in North Carolina’s Wake County Public School System. A ground-up building project designed specifically to accommodate early education, though? That was new, and it was always going to be a learning experience for the state’s largest public school district.

The colorful front facade is meant to evoke the stripes of a caterpiller, which is the Early Learning Center’s mascot. Photo © Tzu Chen Photography

Early this year, the Early Learning Center at Memory Road, a 27,000-square-foot, eight-classroom building, was completed as Wake County School’s first freestanding facility dedicated to pre-kindergarten education. The roughly $15 million center, co-located on the campus of the environmental science–focused Millbrook Magnet Elementary School in Raleigh, was designed by Katherine Hogan Architects (KHA) as the firm’s first new construction project for the district.

Raleigh-based KHA and Wake County Schools have had a modest handful of other collaborations in the past, including the transformative, award-winning renovation of a high school entry hall and the exhaustive yet time- and funding-sensitive prototype modernization of a 1980s-era elementary school. But the Early Learning Center was a new typology for the district. Noting the success of the earlier fast-track, lower-budget commissions, Katherine Hogan, principal of KHA alongside Vincent Petrarca, remarked that Wake County Schools “kind of leans on our office for projects that are a little bit more challenging and non-traditional.”

The center was built at the site of a disused play area on the campus of a magnet elementary school. Photo © Tzu Chen Photography

The Early Learning Center follows down that path and then some. Because of the singular nature of the project, KHA worked closely with Wake County Schools—including, crucially, the district’s Pre-K staff. Together, they developed a new building program that addresses needs identified by Governor Roy Cooper’s NC Early Childhood Action Plan—food security, emotional and academic support, and unfettered access to a high-quality early education among them. The building also had to meet the requirements of a five-star daycare facility due to the age group of the students.

Different colors incorporated throughout the building correspond with different classroom clusters. Photos © Tzu Chen Photography

“Since this was a new building type, they allowed us to do some things that are unconventional,” says Hogan. “But we were still using ordinary materials and didn’t have a big budget, so we had to be inventive within those constraints.”

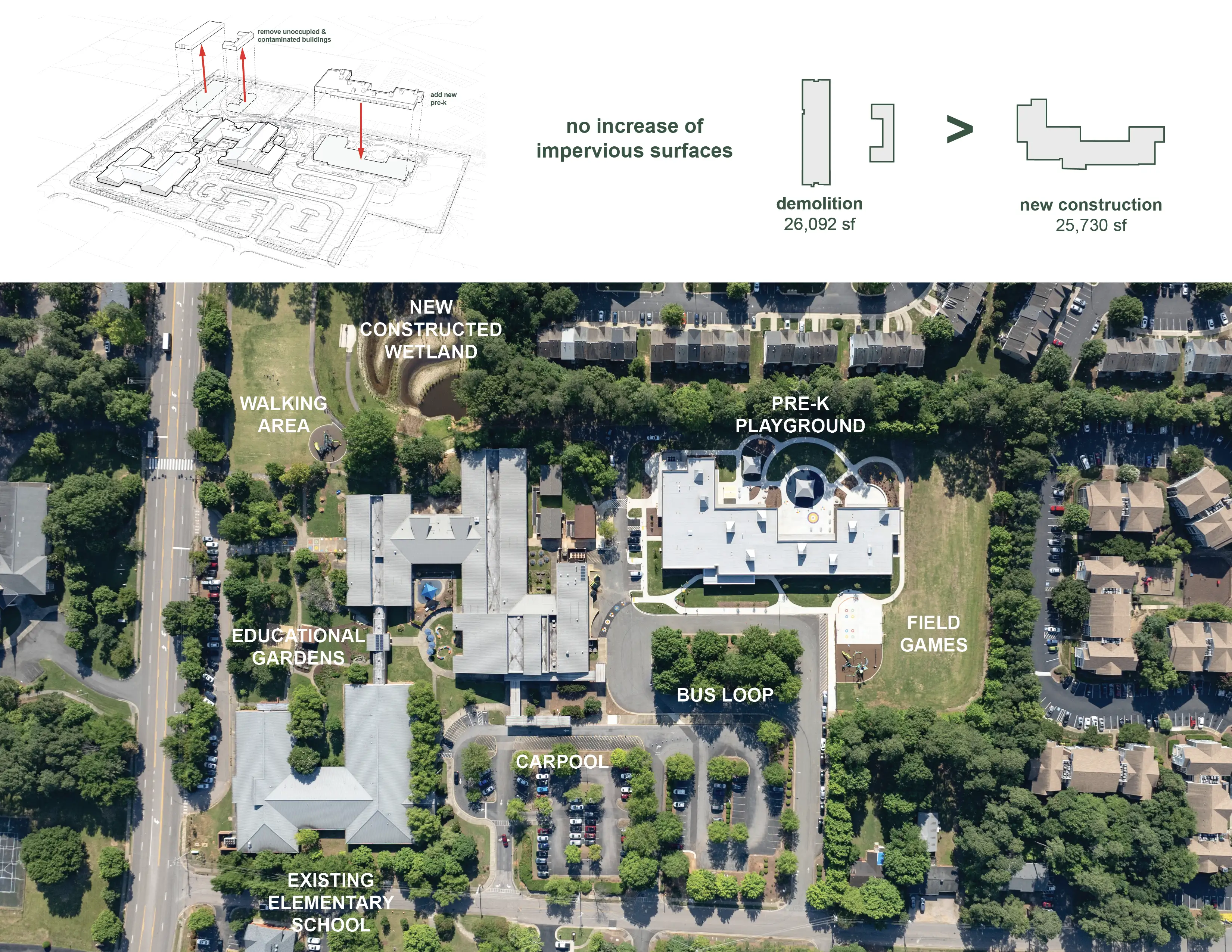

The siting of the Early Learning Center on the existing Millbrook campus, which is bounded by multifamily housing in a growing neighborhood north of downtown Raleigh heavily populated by working families, necessitated a certain ingenuity. The new brick-faced structure, with vibrant pops of (district-approved) color spread across its facade including a caterpillar-inspired band stretching across the front of the building, had to fit into—and stand apart in—its context. The project also needed to tap into several vital resources of the existing campus, including a bus loop, carpool drop off, parking, and the elementary school’s large kitchen, where meals are prepared then brought to the Early Learning Center’s warming kitchen before making it into classrooms.

Photos © Tzu Chen Photography

While the new building takes the place of an unused play area that featured nothing more than a pair of ancient basketball hoops, two long-disused buildings on the site—one from the 1920s, the other from the ‘50s—were also razed to construct a wetland stormwater management system that doubles as an educational tool for Millbrook students. As a result, there was no increase of impervious surfaces at the site as part of the project. “How do you work with existing conditions to build something new that enhances the old as well? That was the real intention,” Hogan says.

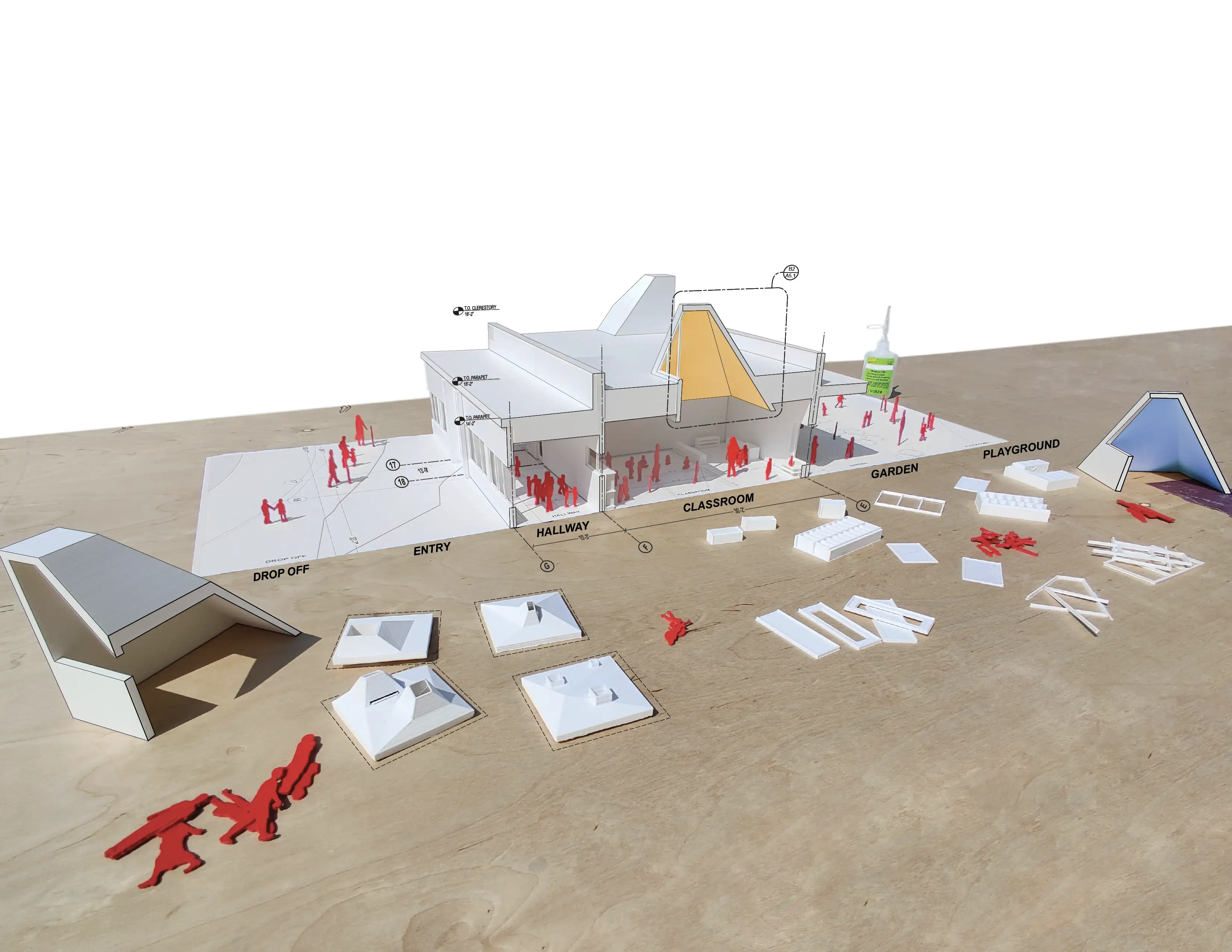

A core component of the Early Learning Center that is unique to the typology is a dedicated evaluation room where educators can observe students to better understand their needs before they start school. There is also a mulitasking lobby, which Hogan compares to a “library collaborative welcome place.” She says it was clear after talking to teachers that the space “needed to be more than just a lobby.”

Because each classroom was required to have direct access to the outdoors, the building plan did not necessitate a double-loaded corridor. This, as Hogan points out, further enhances daylight within the interior while providing a greater connection to the surrounding landscape, which includes a large dedicated Pre-K playground. (Local firm CLH Design served as landscape architect and civil engineer on the project.)

The materials and form of the center are similiar to the existing buildings on the campus, while the use of color and a series of light monitors help it to stand apart. Photo © Tzu Chen Photography

The most conspicuous moment of the Early Learning Center is a series of clerestory monitors emerging from its flat roofline. They draw daylight into the building and serve as welcoming beacons during the early morning and evening hours. Visible from the monitors’ vertical glazing are colors—red, yellow, and green—that correspond with the center’s individual classroom “pods.” As KHA notes, these “apertures glow, signaling the safe space within to students who have the most need for daycare services.”

Photo © Tzu Chen Photography

The light monitors are a signature of the building, but KHA had to consistently push for their approval from a district whose maintenance department was decidedly skylight-adverse. Ultimately, Hogan says, they were saved and incorporated in the final design after educators prepared research on the benefits of direct daylight in the classroom and presented their findings to the powers-that-be. “They listened to the teachers,” she says. “Not the architects, but the teachers.”

Hogan is candid about the challenges of working on a limited budget for a large public school system, where funding is stretched across many—or, in this case, hundreds—of schools and where design historically takes a back seat to maintenance and other matters.

“We fought really hard to make this project have aspects of design that the children can enjoy, and the teachers can be proud of,” she says, noting that additional standalone Pre-K buildings are being considered by the district. “I'm hopeful that Wake County Schools will continue in that way, and although it's not always easy, I think the struggle was absolutely worth it.”

Courtesy Katherine Hogan Architects

Courtesy Katherine Hogan Architects