The Met Tackles Paul Rudolph in Rare Architecture Exhibition

Upon hearing that the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York mounted an exhibition, Materialized Space: The Architecture of Paul Rudolph (on view until March 16, 2025), you might ask, why Rudolph? And why the Met? Paul Rudolph, born in 1918, and trained at Auburn University and Harvard’s Graduate School of Design under Walter Gropius, was once at the top of the heap of second-generation modernist architects. Yet his vaunted visibility had disintegrated by the time he died in 1997. And, for its part, the Met seems to have forgotten for many decades that architecture could be an interesting exhibition topic. Even the press release for the show announces it as “the first major exhibition of 20th-century architecture at the Met in over 50 years.” (Is that a boast? Shouldn’t it be an apology?)

While the museum’s claim refers to the 1972 exhibition Marcel Breuer at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in the intervening years the Met mounted several monographic architectural shows, including The Architecture of R.M. Hunt (1986), Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1996), and Santiago Calatrava: Sculpture into Architecture (2005–06). However, these were not generally conceived as “major” and did not offer much competition for the Museum of Modern Art’s more robust architecture program.

Installation view of Materialized Space. Photo © Eileen Travell, courtesy the Metrpolitan Museum of Art

The organizer of this exhibition, Abraham Thomas, since 2020 the museum’s Daniel Brodsky Curator of Architecture, Design, and Decorative Arts in the Department of Modern and Contemporary Art, says he has had a long fascination with Rudolph. Thomas even brought up his interest in the architect’s legacy when he was interviewed for the Met position. His resuscitation effort did not occur overnight. Raised in England, Thomas received a computer-science degree from the University of Leicester before becoming a curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum and then director of Sir John Soane’s Museum, both in London. That experience and his subsequent positions as curator at the Renwick Gallery and the Arts and Industries Building of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., groomed him for this mission, Rudolph’s first retrospective exhibition.

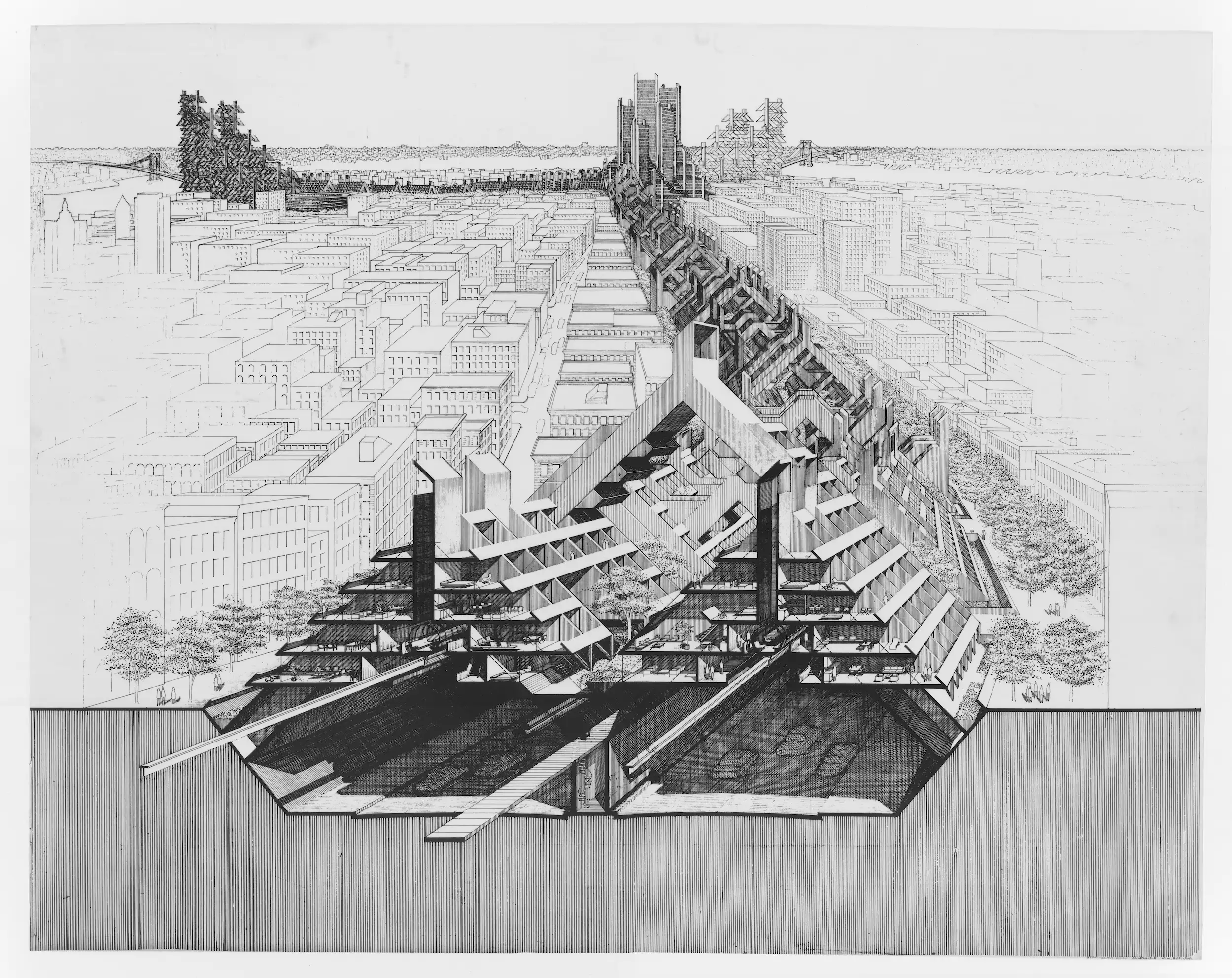

Aerial perspective/section view of the unbuilt Lower Manhattan Expressway/City Corridor. Image © Paul Rudolph Collection, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

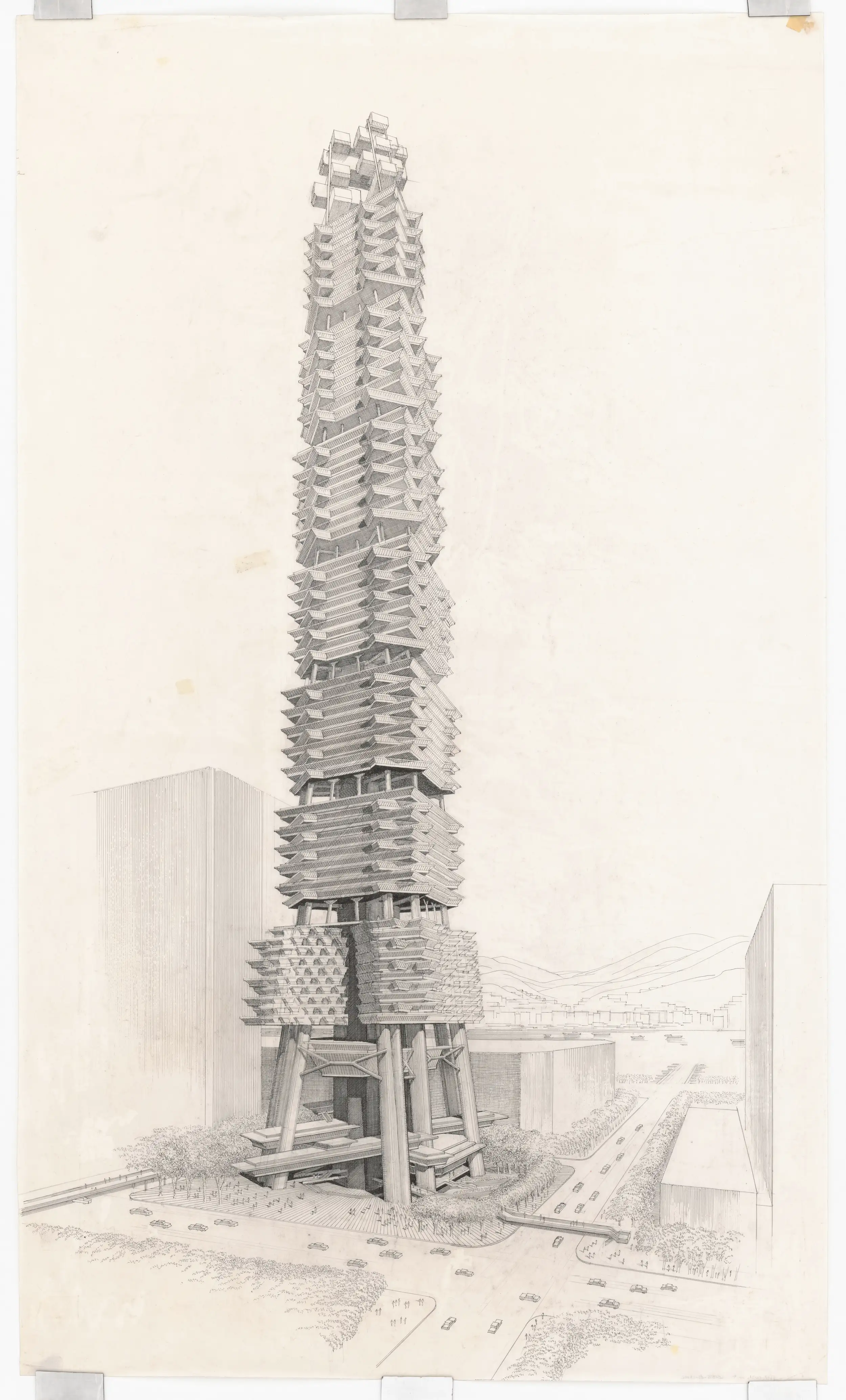

The Materialized Space show is small, displaying over 80 objects in about 3,000 square feet, where deep charcoal gray walls are punched up by vibrant paprika-toned elements. The contained number of drawings, original models, photographs, film clips, and quixotic artifacts creates a manageable viewing experience. It also allows Rudolph’s legendary megastructures, delineated in single-point-perspective drawings, to be displayed with the proper impact. The architect’s famous aerial-perspective view and section of the Lower Manhattan Expressway/City Corridor, an unbuilt project (1967), as well as his perspective section of the approach to the Williamsburg Bridge in the same Lower Manhattan scheme (1972) say it all. If Rudolph didn’t invent the perspective section, he certainly had a patent on it. His exquisite ink and pencil drawings explain why his ideas captivated a public, as did his delicate balsa wood models, such as a tower proposed for the unbuilt Graphic Arts Center (circa 1967), on Manhattan’s West Side. If only those wood models could be literally transposed to physical entities with similar finesse and elegance! Alas, reality gets in the way, a mantra applicable to much of Rudolph’s built work.

More than 80 objects are featured in the gray-and-paprika-colored display. Photos by Eileen Travell, courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The show highlights the architecture Rudolph was best known for—the rugged, Brutalist concrete buildings of the 1960s. The chipped and ribbed poured-in-place-concrete structure of Yale University’s Art & Architecture Building (A&A), opened in 1963, and the less lavish concrete-block Tracey Towers affordable housing (1967), in the Bronx, testify to Rudolph’s initial success in constructing large-scale work with new materials and techniques. The output at that time showed he was not just a visionary “paper architect” who drew but did not build. However, problems cropping up later convinced many that his true achievement was in drawing.

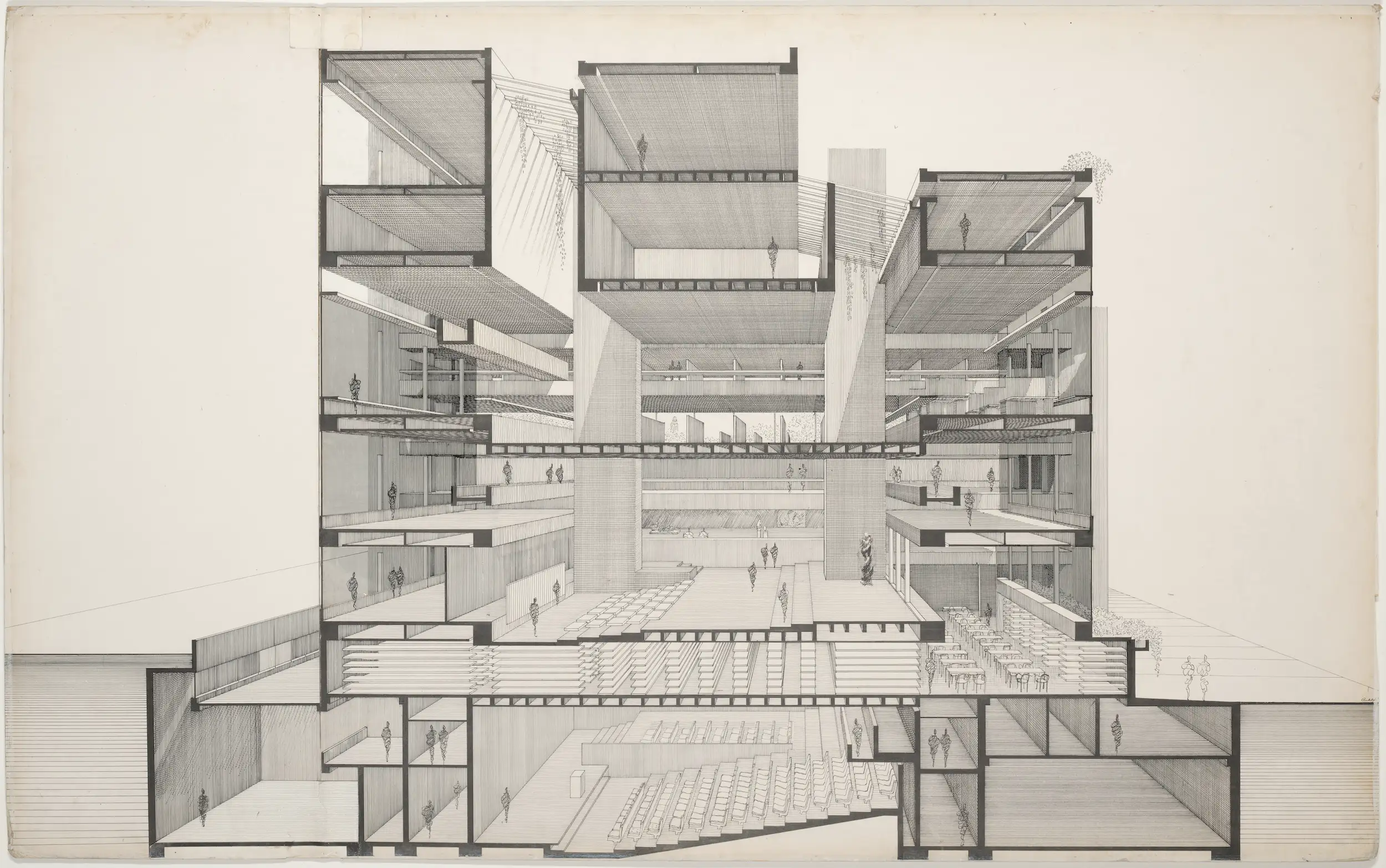

Since the museum-going public may not be very familiar with Rudolph, Thomas conceived of a thematic organization, rather than a chronological one. Visitors enter an area whose focus is the “workplace,” highlighted by a striking perspective section of Rudolph’s first New York office, on West 58th Street—multileveled and linked by floating stairs without handrails. Near the drawing are displays of intriguing appurtenances of the creative process, such as pencils and templates.

As museumgoers weave through the display, they’ll find that Rudolph’s legendary early work of the mid-1940s and 1950s—the lightweight bent-plywood, wood-louvered and -frame Florida houses—come at the end of the installation trajectory, not the beginning. This surprises the didactically inclined of us who seek to understand his evolution. While the thematic organization loops visitors in through urban-renewal schemes, civic and campus complexes, megastructures, and high-rise towers in Asia, as well as with Rudolph’s spatially complex “Experimental Interiors,” the installation has no clear beginning, middle, or end; such an Aristotelian approach is too old-fashioned today.

If you want a better sense of Rudolph’s chronological development—for example, how encounters with industrialized building methods during his years in the U.S. Navy influenced early lightweight houses—turn to the Materialized Space catalogue.

1

2

Perspective drawing of the Sino Tower project (unbuilt), Hong Kong, 1989 (1); architectural model for the proposed Sino Tower (2). Images © Paul Rudolph Collection, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division (1); photo © Eileen Travell, courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art (2)

Rudolph’s work in the later 1980s depended on Asian commissions. The Lippo Centre (1988) in Hong Kong, a double-tower office complex encased in an articulated, reflective glass skin, boldly demonstrates how Rudolph’s sculptural if heavy-handed proclivities were manifested without his needing poured concrete. Yet the conundrum of Rudolph’s career remains: why had his architectural reputation cratered toward the end of his life—to the degree that the Asian work did not matter?

When Rudolph opened his office in New York after being chairman of the department of architecture at Yale University (1958–65), it was not long before The New York Times Magazine hailed him as the successor to Le Corbusier. But, by the late 1970s and the ’80s, Rudolph had neither the commissions nor public fanfare. Even essays and talks by admirers such as critic Michael Sorkin and architect George Ranalli could not put the stature of this crew-cut Humpty Dumpty back together again.

3

4

Rudolph’s A&A at Yale University (3) features a core with double-height interiors (4). Photo © Ezra Stoller/Esto, Yossi Milo Gallery (3); Image courtesy Yale University, Manuscripts and Archives, Yale University Library (4)

The cause largely seems to stem from problems with the built work. After Yale’s A&A opened, complaints spewed forth about the building’s poor ventilation and how gobs of asbestos sprayed on the ceilings were starting to flake off. The painting and sculpture students complained vociferously about being stuck with either low-ceilinged spaces at the top level or in the subterranean studios. (Guess where the architecture students were? The airy middle.) A suspicious fire in 1969 didn’t help. Although the asbestos was removed in 1973, not until the A&A was upgraded and renovated by Gwathmey Siegel & Associates in 2008 was it finally appreciated. But it was too late for Rudolph, who had died of mesothelioma, a cancer often caused by asbestos.

Interior of the Hirsch-Halston House, East 63rd Street, New York, in 1969. Photo © Ezra Stoller/Esto, Yossi Milo Gallery .

And there were those prickly lawsuits. According to biographer Timothy M. Rohan, in 1974 Rudolph admitted to a friend he had “at least seven ongoing lawsuits, but left it to his lawyers to worry about these problems.” The attorneys stayed busy: the Earl W. Brydges Building of the Niagara Falls Public Library (1974) sued Rudolph for leaks in 1981; the Orange County Government Center (1971), in Goshen, New York, ended up in litigation in 1975 over various drawbacks, including leaks, before eventually being partially razed. Cost overruns plagued construction, as was the case at the Boston Government Center (1971), which was never completed. Even nature had its turn: Rudolph’s Sanderling Beach Club Cabanas (1952), in Sarasota, Florida, were destroyed by Hurricane Helene in September.

Many adventurous, path-breaking works of architecture fall apart without proper construction or maintenance, not just those by Paul Rudolph. A lot of famous architects are accused of hubris. Rudolph may have gotten more than his fair share of criticism about both, but only in large exhibitions can questions of the true significance of his work be fully addressed.

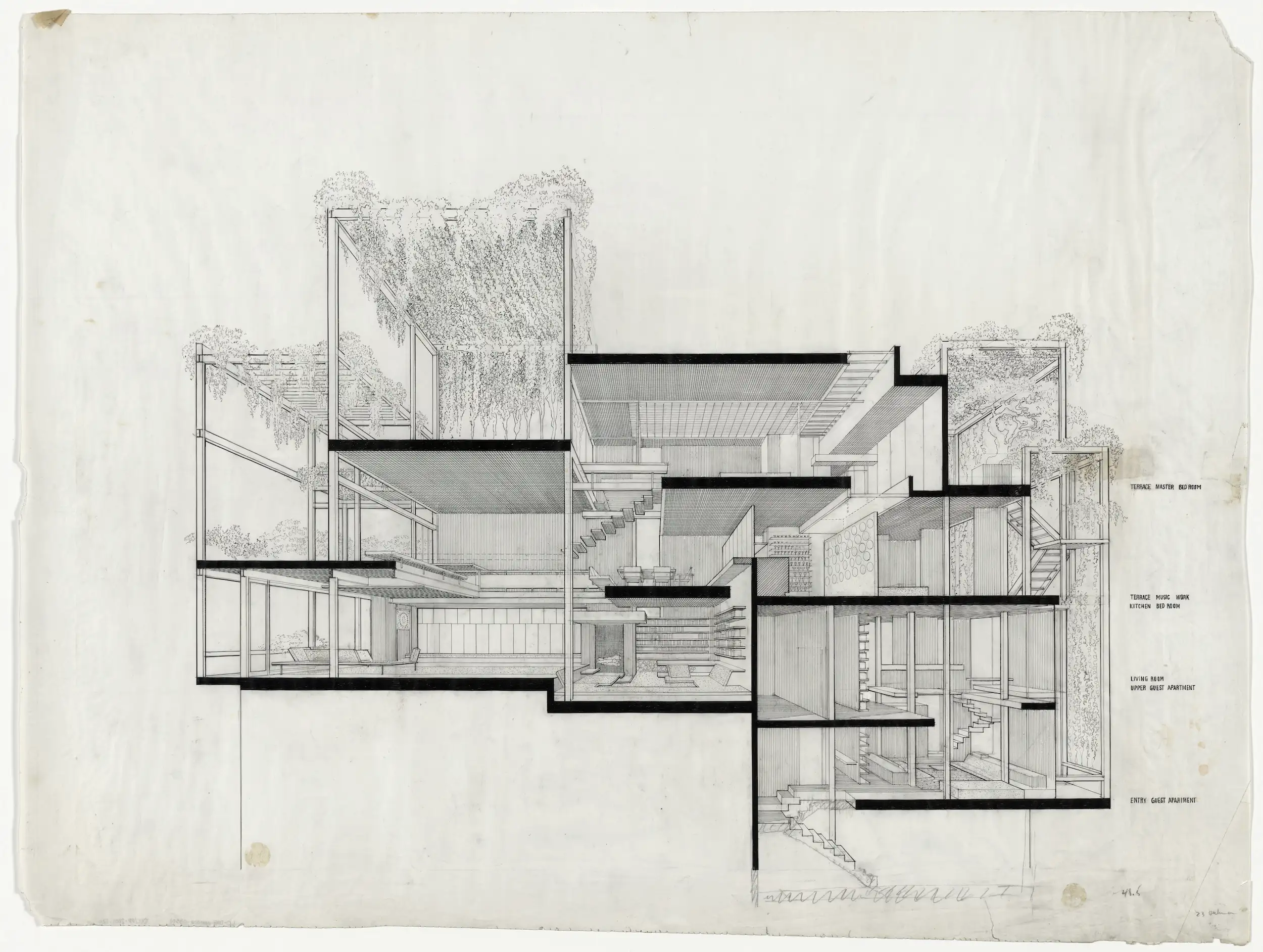

Perspective section drawing of the quadruplex apartment at 23 Beekman Place, New York, 1976. Image © Paul Rudolph Collection, Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

Therein lies another problem—the limited size of the show. Some designs by Rudolph, such as the much raved-about Bass House (1976), in Fort Worth, have not been published in any real depth, owing to the owners’ privacy demands. Yet its presence in the show is minimal. Even Rudolph’s own stunning and terrifying, spatially complex, glass-bridged Beekman Place Townhouse in New York needs more coverage. Another interior that would benefit from more photographs and drawings is the Hirsch Townhouse (1967) on East 63rd Street, better known by the name of its subsequent owner, Halston. Spaces flow and planes levitate, but the area allocated to the house in the exhibition doesn’t allow viewers to get a full sense of that.

Because of both the thematic organization and the pared-down nature of the display, it is hard to reach a conclusion about the importance of Rudolph’s ambitious but often flawed oeuvre. The Met and Abraham Thomas nevertheless have made a significant first step in highlighting his strengths (and weaknesses). Since the career conundrum still hangs over the show, we are left with the observation that Rudolph often included artifacts from buildings by Louis Sullivan in his own projects—ironically, another architect noted for his fabled ascent and decline. Did Rudolph sense that he too might end up that way? What can other architects do to avoid this ending? There is much to investigate.