K-12 Schools 2024

Bohlin Cywinski Jackson's Mass-Timber Addition to a Texas School Offers a Lesson in Sustainable Design

Addison, Texas

Architects & Firms

Located in the Dallas suburb of Addison, the Greenhill School is home to one of the more unusual campuses in the United States, and not just because of the peacocks (technically, peafowl) that wander freely about its 75 acres. The school, which was founded in 1950 as a coeducational, secular institution serving grades K–12, has a unique architectural tradition established by the pioneering Texas modernist O’Neil Ford, who designed five of the school’s first buildings.

Ford’s vision of a campus of modest buildings composed of warm brick that embrace their surroundings has been carried forward over the years by a series of leading architects, among them Gwathmey Siegel, Lake|Flato, and Weiss Manfredi. The latest addition to that assemblage, the 67,400-square-foot, $29 million Rosa O. Valdes STEM + Innovation Center, is the work of Bohlin Cywinski Jackson (BCJ), and follows neatly in the school’s aesthetic tradition while also pushing it in a new, more sustainable direction.

“We didn’t want it to be a spaceship that was just dropped into the middle of campus,” says Lee Hark, the head of school. “At the same time, it was an opportunity for us to do something forward-thinking and distinctive.”

The new building takes inspiration from the one it replaces, Ford’s 1963 Agnich Science Building, which had been dramatically compromised, its central courtyard filled in to make space for additional classrooms. It occupies the same rectangular footprint as Ford’s original structure, with the addition of a wing that extends off its southern flank. Like its progenitor, the Valdes Building is clad in warm, buff-colored brick, with Ford’s central courtyard recreated (the landscape is by OJB) to provide a gathering space for students while introducing light into the building core.

“That extended the heritage of the O’Neil Ford building, so it didn’t feel like necessarily a drastic departure, but it was kind of a progressive continuation of the original building,” says Daniel Lee, a principal in BCJ’s Philadelphia office.

Providing a sense of transparency was an essential goal of the project. “We wanted kids to be able to see the teaching and learning that was happening in all these different spaces,” says Hark. To that end, classrooms and laboratories have large windows facing broad public hallways. On the southeast corner of the building, a “high bay” innovation lab has tall windows facing the school’s central quadrangle, advertising the student activities within.

The glass-enclosed high-bay innovation lab (above and top of page) faces a central quadrangle. Photo © Nic Lehoux, click to enlarge.

Throughout the building, light filters down from north-facing skylights that, from the outside, give the two-story structure a distinctive sawtooth profile. Glazed facades on the building’s southern perimeter are shielded by a screen of horizontal aluminum louvers.

1

2

North-facing classroom skylights (1) lend the exterior a sawtooth profile (2). Photos © Nic Lehoux

The building’s exposed mass-timber structure, with a glulam frame and cross-laminated timber (CLT) floor slabs, adds to the sense of brightness on the interior. The system was chosen for its sustainability but also for its expedience; the pandemic pushed back the construction schedule, but the school insisted on maintaining its summer 2024 move-in date. Mass timber’s off-site fabrication and quick on-site erection helped meet this target.

Most of the timber was sourced from a plant in Dothan, Alabama. “Bringing in mass timber is great, but boating it in from Europe or somewhere didn’t quite make that equation as appealing,” says Lee. That produced something of a challenge: the Dothan plant only turned out CLT panels of southern yellow pine, which didn’t meet BCJ’s aesthetic standards. Their solution: create a layered sandwich of yellow pine from Dothan with an outer layer of more appealing Douglas fir from a plant in Montana.

The building’s systems were designed with a didactic purpose. “We wanted the building to be a teaching tool itself,” says Kendra Grace, the associate head of school. “That’s why you have the exposed ductwork and why everything is labeled, so that the kids can understand where the hot and cold water come from.”

In the central courtyard, what the architects call a “rain veil” makes the capture of rainwater a visible process. As water sheets off the roof, it is guided down chains and through a series of filtering swales, eventually making its way to a water tower that had long been a school icon, even as it had fallen out of use.

In the central courtyard, a “rain veil” makes the capture of rainwater a visible process. Photo © Nic Lehoux

Not all of the building’s sustainable features are quite so visible. In the basement, 10 ice tanks, each one 89 inches in diameter, drive the building’s cooling system. Water is frozen overnight, when energy rates are low, and then used for cooling during peak daytime hours.

Beneath the floorboards, the architects left a 12-inch gap, or plenum, to accommodate changing infrastructural demands. “People kept asking us, how do you know what science education, what math education is going to be like in 10 years? And, of course, we don’t know,” says Hark. For that reason, classrooms have water and gas supplies on their edges, with power supply dropping from the ceiling. “If they need to reconfigure rooms one year, five years, 10 years down the line, that really gives them that flexibility,” says Lee.

Students can gather on a bleacher stair or in the adjoining open lobby. Photo © Nic Lehoux

A mathematical puzzle is encoded in a stairwell wall. Photo © Nic Lehoux

Above all, the building creates an inviting place for gathering in Greenhill’s sprawling and uncentralized campus. Students can assemble in an open lobby area with movable tables and chairs, or sit on a large bleacher stair linking the building’s floors. There’s even coffee: a popular local chain will operate a café adjacent to the building’s main entry.

One thing students can discuss, as they drink their caffeinated beverages, is a pattern built into a brick wall enclosing a stairwell on the building’s south facade. That design is a mathematical puzzle waiting to be solved. “One of these days, we hope to get some notification from a student who has the solution,” says Lee.

For now, the building is its own winning formula.

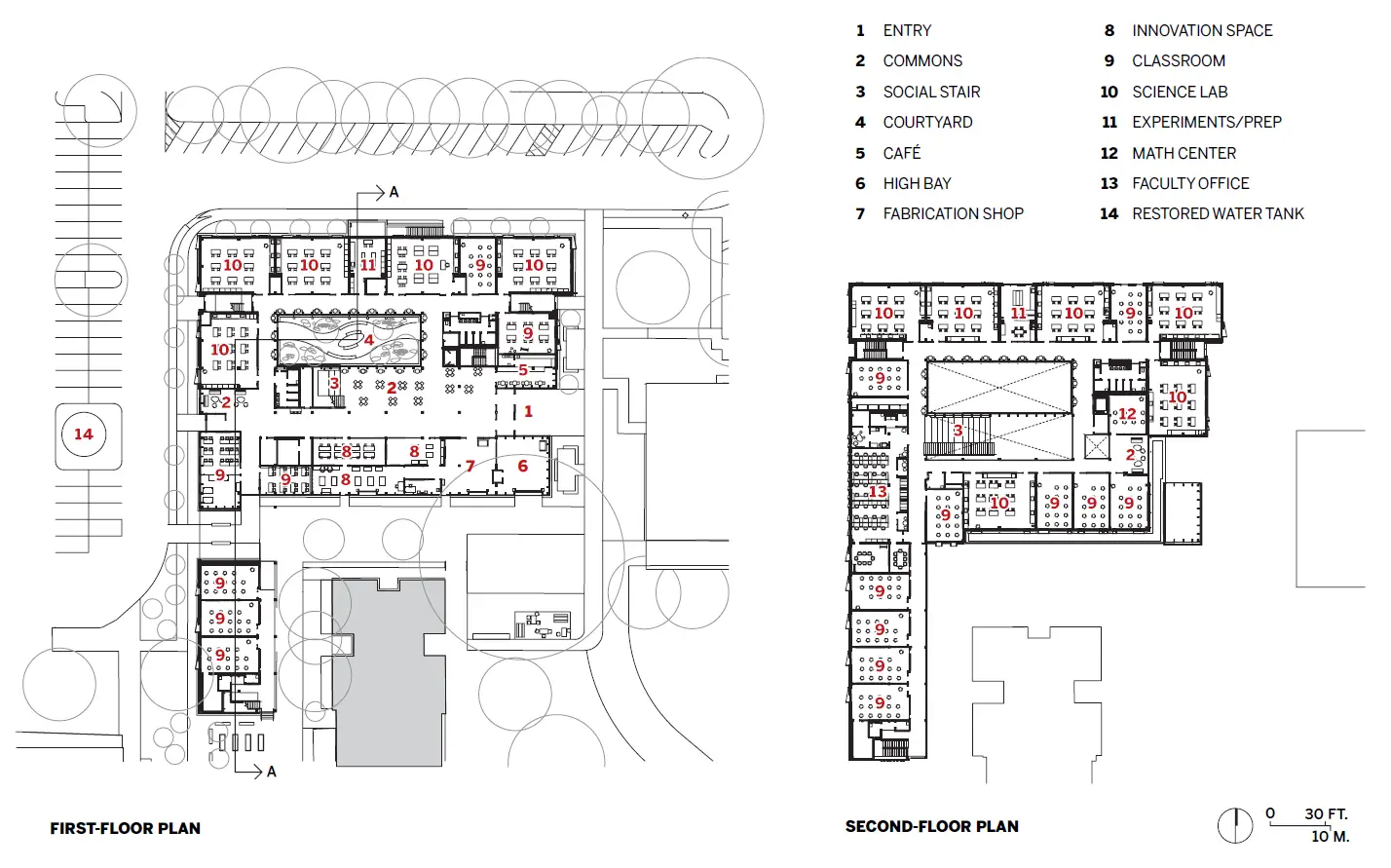

Click plans to enlarge

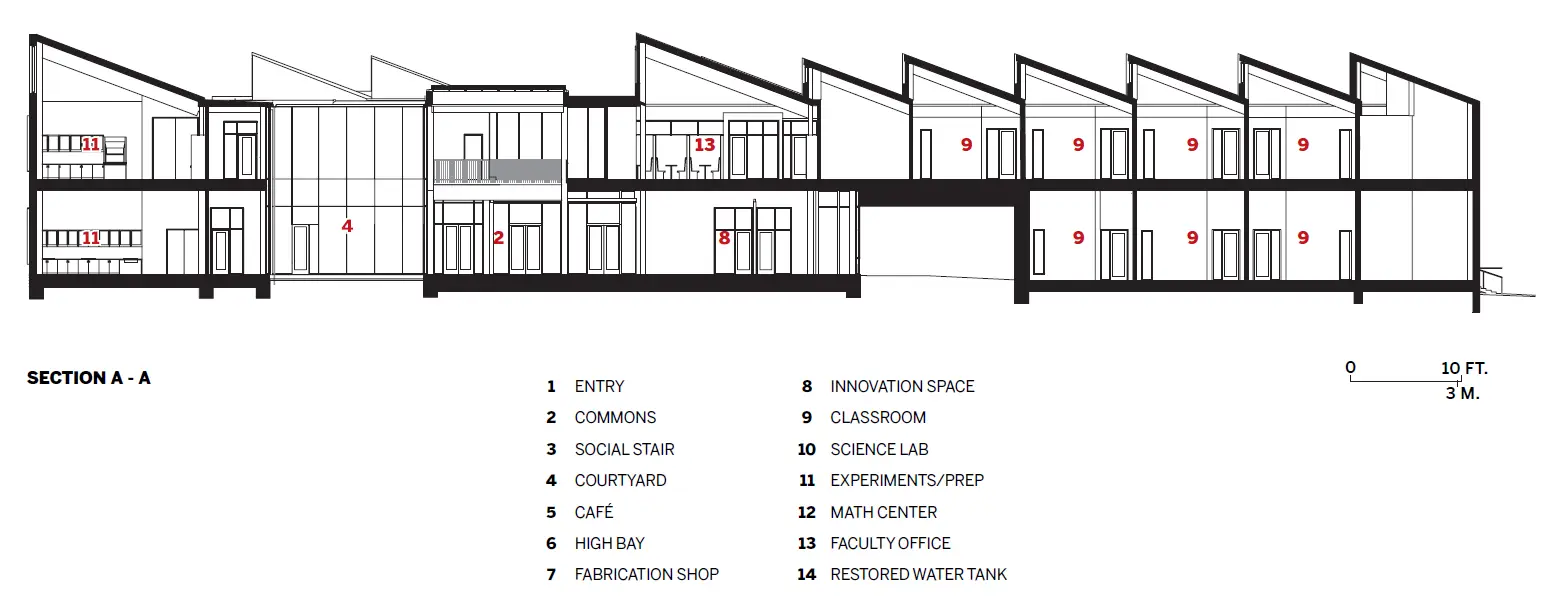

Click section to enlarge

Credits

Architect:

Bohlin Cywinski Jackson — Daniel Lee, Tom Kirk, principals; Margaret Sledge, project manager; Habeeb Muhammad, Tom Breslin, Judy Chang, Nicolas DelCastillo, Chris Renn, Chuck Nawoj, Nora Chase, project team

Consultants:

Walter P. Moore (structural); DBR Engineering Consultants (m/e/p/fp, data/telecom); Westwood (civil); OJB (landscape); Holmes Keogh Associates (code); Metropolitan Acoustics (acoustics)

General Contractor:

Scott + Reid

Client:

Greenhill School

Size:

67,400 square feet

Cost:

$29 million

Completion Date:

April 2024

Sources

Mass Timber:

SmartLam

Masonry:

Acme Brick

Curtain Wall:

Oldcastle BuildingEnvelope

Wood Cladding:

Nakamoto Forestry

Glazing:

Guardian

Skylights:

H&H Skylight Fabricators

Bird Frit:

NGS Films and Graphics

Doors:

NanaWall, Republic, VY Industries, Cookson Door, TGP, Renlita

Hardware:

Schlage, Von Duprin, LCN, Ives

Ice Tanks:

Calmac

Acoustical Ceilings:

Cardinal Acoustics

Faucets:

Chicago Faucets, T&S Brass and Bronze Works