When The Line, the infamous 106-mile-long linear city proposed by Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, was announced in 2021, it was quickly derided in architectural circles—despite the reported involvement of such noted figures as Thom Mayne and former Archigram member Peter Cook. The project, if we are to believe the renderings, will appear as a mirrored blade, complete with greenwashed tufts, relentlessly cleaving the desert on the northern shores of the Red Sea. It comes to us as a revenant, as if the gridded ghost of Superstudio’s mirrored Continuous Monument (1969–70) appeared unironically, without comment, without consequence. The first thing that came to mind while mulling over its ensemble of excessive linearity was the scene from David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia (1962) when T.E. Lawrence, played famously by Peter O’Toole, realized that the best way to overrun the Turkish stronghold at Aqaba was to approach from deep in the desert and attack from behind, because, as the film brilliantly depicts, the giant, building-size cannons are lined up (yes, lined up) toward the water on rail mounts and cannot face backward. What is the architectural metaphor that needs unpacking here? Does it have something to do with how, in the middle of the arid landscape, an imposing yet purposeless object serves as a stark reminder of human folly? Or do these imposing, useless cannons, captured in a perpetual forward gaze, remind us of the inability to look backward, which, if you think about it, finds a parallel in The Line’s forward march in complete disregard of historical consciousness and reflection.

Today, The Line is a fragment of its former self, a 1.5-mile-long segment under construction, with only vague promises of future completion. Some of the architects have bowed out, notably including Mayne. It’s certainly a “colossal Wreck” that succumbs to the “lone and level sands,” as Shelley reminds us in “Ozymandias,” his own paean to useless monuments fading away in the desert. Yet, even in this diminished state, the project continues to incite skepticism. Perhaps this is the fate of any such project. Indeed, we might envision past audiences grappling with Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City or Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin—projects that, well argued or not, were meant to function as critiques of urban design. So what is it about The Line that continues to irk? Is it the project’s unimaginable (even if drastically reduced) size? Perhaps it’s the project’s formal conceit, the way its colossal, mirrored-wide-flange beam slices effortlessly through the desert, an advertisement for half-baked notions of urban life and technology. Or is it the stark reality that such an endeavor could only materialize through the deployment of vast amounts of conscripted labor, extracted resources, and capital investment, and that Saudi Arabia seems willing to crush resistance of any kind?

Perhaps we’re witnessing an instance of Marx’s famed adage, “the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce,” with The Line emerging as a derivative work, an echo of an echo of linear cities of yore. But what does it mean to have something like this arrive on our collective doorstep today, so bereft of any critical reflection, so unknowing of its own origins among the maneuverings of history? The Line’s gleaming, sterile renderings seem to confirm how architecture celebrates its Candide-like optimism in technology, a conscious detachment from worldly realities. The rush to draw parallels and connections between The Line and other outlandish schemes from the past is understandable, sometimes requisite. After all, this is a project that reflects some of the worst impulses in contemporary architectural practice and, because of this, it promises to live in our historical consciousness neither as embarrassment, failed scheme, or bad architecture but rather as an exemplar of that most convenient and hence overused category—the dystopia.

This is tempting, problematic, even inaccurate, for dystopia’s opposite, utopia, shares many of its characteristics. Utopia too aims for an architecture deliberately removed from the textures of reality, yet utopian projects are hardly spared the imperfections and controversies that inspired them. Perhaps it’s more apt to categorize something like The Line as speculation freed from the burden of utopia. An alternative vision is just that—a departure, a willingness to extract a project from the intricate web of social, political, and economic contexts that threaten its existence.

A 1930 Soviet magazine depicts Ivan Leonidov’s linear proposal for Magnitogorsk, an industrial hub in the Ural Mountains. Image courtesy Sovremennaia Arkhitektura, click to enlarge.

The history of architecture is replete with urban proposals characterized by explicit, purposeful linearity, many addressing genuine concerns. Some, like The Line, are marked by a sense of inevitable failure. Consider the Spanish engineer Arturo Soria y Mata’s Linear City proposal from 1882—an elongated spine facilitating the expansion of housing and manufacturing zones while minimizing physical and ecological impact. This concept resonated in subsequent schemes, notably Kenzō Tange’s 1960 Tokyo Bay project, whose spines extended into the water to accommodate additional housing modules. These proposals blurred the line (so to speak) between architecture and infrastructure, presaging Reyner Banham’s 1970s concept of “Megastructure”—inhabitable infrastructure writ large. Linear projects have also often served ideological agendas, particularly in the Soviet Union. Mikhail Okhitovich’s “disurbanist” proposals found new life in Nikolay Alexandrovich Milyutin’s linear Sotsgorod (1930). Concurrently, Ivan Leonidov, collaborating with the Organization of Contemporary Architects (OSA), developed a formally similar plan for the city of Magnitogorsk in the Urals. All embraced linear organization as a novel spatial response to rapid industrialization. While many remained theoretical, some concepts materialized—the southwestern Russian city of Volgograd’s expansive system of infrastructural trunks and branches bears the unmistakable imprint of these Soviet schemes. This rich tapestry of linear urban planning underscores The Line’s place in a long-standing architectural tradition, albeit one that in the past grappled more substantively with real-world challenges and ideological imperatives.

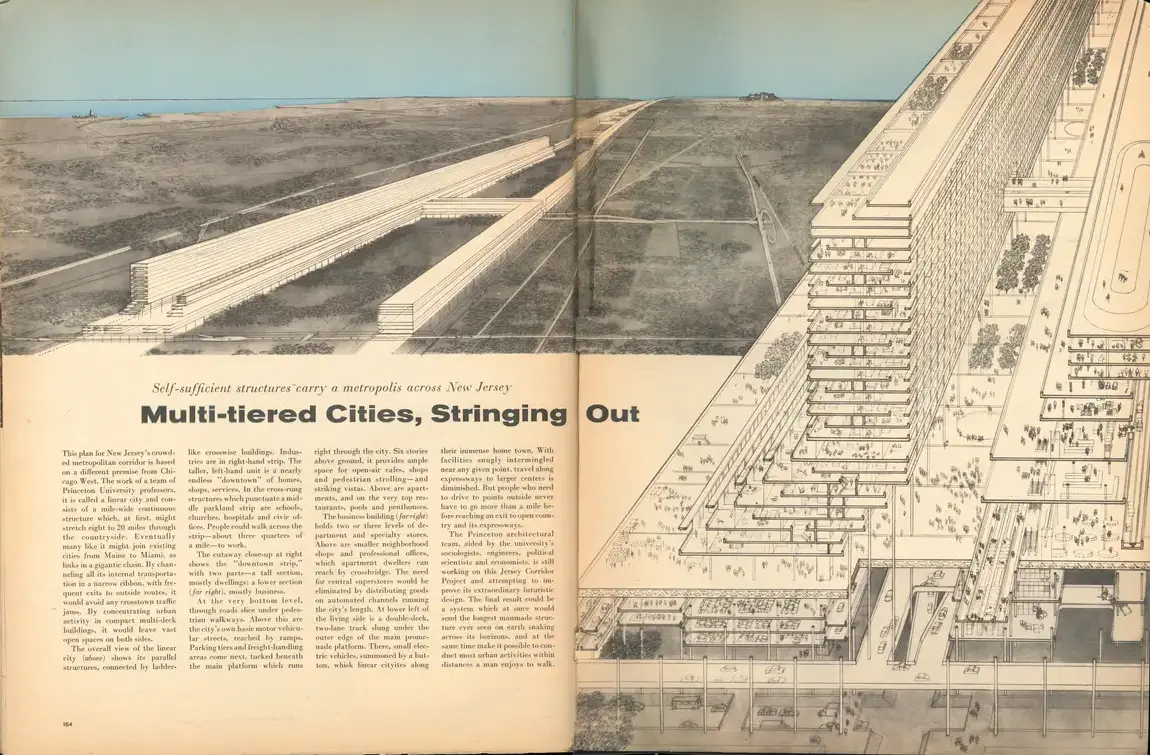

Linearity can be burdensome, to paraphrase architectural theorist Catherine Ingraham. And it tends to underscore existing realities rather than transcend them. Take, for instance, Peter Eisenman and Michael Graves’s 1965 Linear City—a proposed 22-mile urban megastructure linking segments of the Interstate 95 corridor. While ostensibly flexible and infrastructural, it inadvertently mirrored trends in urbanization and industrialization, echoing developments along the U.S. Highway 1 corridor between Trenton and New York, and the industrial dystopias immortalized in Robert Smithson’s 1967 Artforum piece, “The Monuments of Passaic.” The burden of linearity becomes particularly acute when, at the level of critique, these concepts descend into reductio ad absurdum. This realm is exemplified by speculative linear projects like the Continuous Monument or Archizoom’s No Stop City (1969–72), which push the concept to its logical—and absurd—extremes, illuminating the inherent limitations of megastructural linear design.

Peter Eisenman and Michael Graves’s 1965 Linear City proposal (above) prefigures the geometries of The Line (top of page). Image © Life Magazine

The Line compels us to evaluate whether the very concept of linearity can make sense in a world wracked by environmental crises, social injustice, and economic inequality. It certainly does not help that The Line exists mainly as exquisite renderings—slick, technical images whose very purpose is to secure an influx of capital. The result is alienating. The Line is so confounding because it appears as a megastructure-sized incision that treats the delicate desert ecosystem as though it were a smooth, isotropic space, devoid of obstacles and primed for the realization of pure geometry. This approach reflects a voracious appetite for terrestrial alteration in service of a grandiose vision. The image that captures it best is Walter De Maria’s “Mile Long Drawing” (1968), with its prostrate figure at the terminus of two lines, seemingly yearning for infinity yet constrained by the ultimate human limitation that is death itself.