In Denver’s gritty, graffitied, postindustrial northeast, where local creatives have long flocked, developers have been busily transforming surface parking lots and former warehouses near the Union Pacific depot into new housing stock. When the din of construction equipment finally clears and the nearby tracks are free of passing trains, the sound of running water cuts through the silence. Where is it coming from? One might expect this while trekking through the Rockies, where runoff and snowmelt form brooks and creeks—but not here, on a sidewalk in the semi-arid Eastern Plains. What’s more, the trickling sound emanates from above.

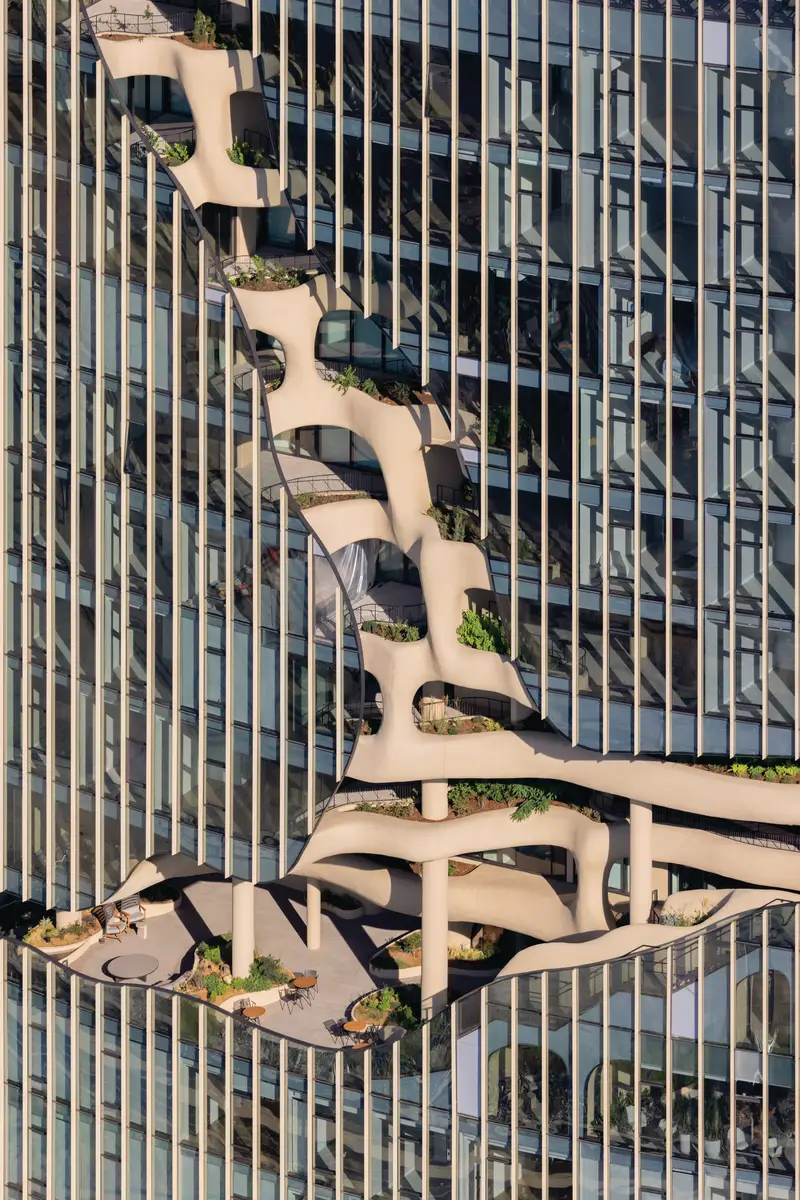

Bringing home a slice of the far-flung wilderness was the principal idea behind MAD Architects’ One River North, a 187-unit apartment building. The designers furrowed a meandering biomorphic channel—peppered with vegetation and a cascading water feature—into the upper reaches of the 16-story building’s bowed, glazed curtain wall. This inhabitable space was not only intended to attract outdoorsy tenants, but it reflects the pandemic era in which the project was conceived. “We were going through all these studies while stuck inside,” says project director Jon Kontuly. “Creating spaces where people could still be together, but be outside, was really ideal,” he adds, with physical, mental, and social well-being top of mind.

1

Biomorphic plaster walls define the spaces of the shared terraces and amenities (1) as well as the lobby (2). Photos © Iwan Baan, click to enlarge.

2

Biophilia is a word the architects of One River North repeat often. They liken the experience of traversing this “canyon” to that of hiking a trail—one that begins at the cavelike lobby and, after a brief detour through a nondescript double-loaded corridor, resumes on the sixth floor. Here, an escarpment of shared terraces and amenities sinuously ascends four stories, forming intimate pockets and exposed plateaus for people to congregate in and on, as well as inviting a certain exploration. “The idea is that residents are moving through different biomes, without actually going up 10,000 feet,” says Kontuly of the journey. From the ninth floor, the channel continues upward to the “alpine” roof deck, leaving in its wake one-of-a-kind balconies—each seemingly with its own microclimate—at 18 of One River North’s rentable units. Much of the building is otherwise straightforward (apartments range from about $2,500 to $15,000 per month), and the three remaining facades are mostly clad in strips of bland and blocky EIFS. But, for the time being, the attention-grabbing north facade is a prominent marker on the Denver skyline, due to its relative distance from downtown and nearby construction that has yet to break ground.

3

4

A rendering (3) depicts what One River North’s terraced “canyon” (4) could look like once plants have matured. Image © MAD Architects (3), photo © Iwan Baan (4)

To create the sculpted walls, MAD turned to digital tools. “A lot of it was trying out things in Rhino, rendering, and seeing what worked,” says Kontuly of the trial-by-error process. The 3D model was then translated into a real-world patchwork of over 700 panels given form by a grid of CNC-bent galvanized bars sheathed in expanded metal mesh, lath, and hand-troweled plaster. Despite all the talk of biophilia, the architects contend that imitation of nature was not the final objective. Perhaps because of this, up close, the surfaces appear rather lifeless—without stonelike stratification, craggy ruggedness, or traces of the forces that cause erosion. Unsightly seams between the panels remind residents and guests of the wall assembly’s artificiality.

This critique may be moot once the landscape has an opportunity to take root, mature, and fill the spaces. Early renderings of One River North depict a lushly planted crevice, brimming with vegetation and scandent vines wrapping structural columns today left sorely exposed. “Everything is a bit smaller than I would have hoped from day one,” says landscape architect Jeff Stoecklein at architect-of-record Davis Partnership, adding that development across the state has depleted nursery inventories. This issue plagues many projects aiming to integrate the built and natural worlds, such as Stefano Boeri’s seminal Bosco Verticale, which appeared similarly underplanted when it opened in 2014 but now stands as a flourishing, verdant tower. In Milan, however, Boeri’s project benefits from full and direct sun, as well as a central irrigation system that minimizes upkeep. One River North has only one of those two things, prompting reasonable skepticism.

“One of the challenges is the northwest orientation. We’re in shade, and that’s tough for our plant palette,” says Stoecklein, who worked with MAD to refine its initial landscape scheme to better suit the state’s four-season climate. Even with a mix of native and resilient pine, aspen, grasses, and drought-resistant sedum taking the place of other deciduous trees and subtropical vines, Stoecklein anticipates a higher level of mortality than usual during the first few years. He is currently working on a long-term maintenance plan with Colorado State University’s horticulture program and an irrigation consultant, but whether or not developers will follow it remains to be seen. One River North has the potential to go the way of the Bosco Verticale, but in the wrong hands it may also end up like Herzog & de Meuron’s Pérez Art Museum in Miami, which recently replaced its hanging gardens with columns of plastic turf.

Despite a Fitwel certification, the insertion of greenery, and inspiration taken from Colorado’s diverse natural landscape, sustainability efforts at One River North are largely confined to standard high-efficiency mechanical and plumbing systems. But architects and the public must be wary of biophilia masquerading as environmentally responsible building—especially if the former comes at the expense of the very habitats such projects claim to celebrate. Designers need not fall for the false dichotomy of choosing between sustainability or daring experimentation with material and form. The true challenge facing professionals today is tackling both, head-on.

Click plans to enlarge

Click image to enlarge

Credits

Architect:

MAD Architects — Ma Yansong, Dang Qun, Yosuke Hayano, partners in charge; Jon Kontuly, Flora Lee, Peng Xie, Edwin Cho, Horace Hou, Yunfei Qiu, Evan Shaner, Shawna Chengxiang Meng, project team

Architect of Record:

Davis Partnership Architects

Engineers:

Jirsa Hedrick (structural); ME Engineers (m/e/p)

Consultants: Kimley-Horn (civil); Marx Okubo (waterproofing); Geiler & Associates (acoustics); Group 14 (energy modeling); CPP (wind analysis); HKS&S (rainscreen)

General Contractor:

Saunders Construction

Client:

The Max Collaborative

Size:

342,675 square feet

Cost:

Withheld

Completion:

September 2024

Sources

Roofing:

Carlisle, Hanover, Bison

Glazing:

Vitro, Millet

Doors:

Oldcastle BuildingEnvelope, Trulite, Assa Abloy, SaftiFirst, Rytec

Locksets:

Schlage, Falcon Lock

Lighting:

B-K, Erco, Aculux, Kelvix, LED Linear USA, Gotham

Interior Finishes:

Sherwin-Williams, Benjamin Moore (paints); Graniti Fiandre, Bedrosians (tiles)