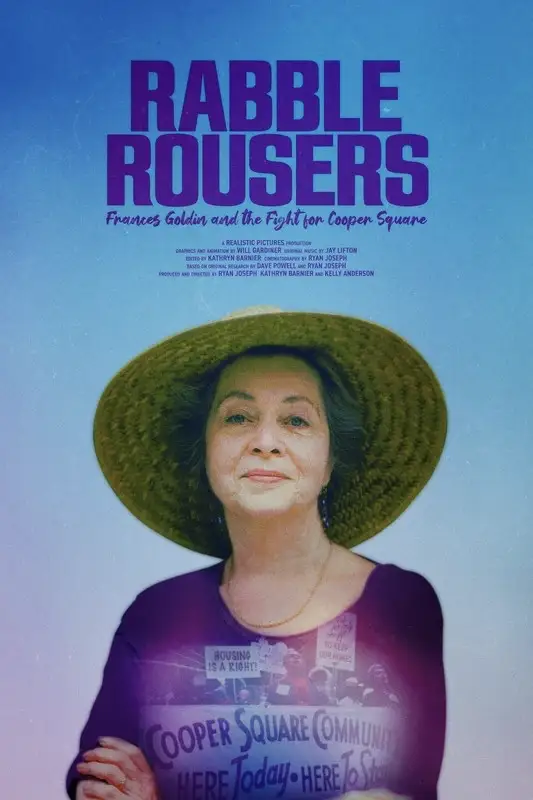

‘Rabble Rousers’ Champions Community Activist Frances Goldin and Grapples with the Past, Present, and Future of Urban Development

Rabble Rousers: Frances Goldin and the Fight for Cooper Square, screening September 25 at the 2024 New York edition of the Architecture & Design Film Festival, is a respectable dual portrait of the legendary Lower East Side organizer and the Manhattan neighborhood she vigorously defended for six decades. But where Kelly Anderson, Kathryn Barnier, and Ryan Joseph’s film excels is as a celebration of the common man rather than the great man—of the endless daily struggle and bottomless courage it takes to protect a community from rapacious developers.

Courtesy Realistic Pictures

Goldin’s fight spanned 60 years, ending when she died at 95 in 2020. It began, inevitably, with Robert Moses, who in 1959 targeted Cooper Square—the area bounded east to west by Second and Third Avenues and north to south by Ninth Street and Delancey Street—for slum clearance. But this isn't Jane Jacobs redux. Goldin’s defense of her neighborhood was bigger than Moses and his machinations. And rather than allow that infamous “power broker” to overwhelm the narrative, the filmmakers reject the standard depiction of Moses as urban renewal’s villainous mastermind, locating him instead as an agent of a more common, pernicious master: the government.

When Goldin arrived on the Lower East Side in 1944 as a 20 year old, it was a true melting pot of immigrants, minorities, and the working poor. She “had found nirvana” and refused to allow Moses, or anyone else, to destroy it. And as a hardened veteran of the housing and urban renewal wars, helping impoverished tenants remain in their apartments and unsuccessfully campaigning to save the Upper West Side neighborhood of San Juan Hill (now Lincoln Square), she knew how to push back. Goldin and like-minded neighbors formed the solutions-focused Cooper Square Committee, then hired city planner Walter Thabit to create an alternative to Moses’ plan, which would have destroyed the character of Cooper Square and made it unaffordable to 93 percent of its then residents. “We threw our lot with the 93 percent,” Goldin says in the film.

Film still courtesy Kelly Anderson

It was, literally, the work of a lifetime—work that was bigger than Moses, and, indeed, Goldin. We hear from her and many of her committee colleagues and neighbors recalling the fights with three mayors, surviving years of benign neglect, and holding off the first waves of gentrification. In the end, they secured a community land trust and a mutual housing association for Cooper Square that renovated 21 blocks and created 328 low-income apartments under cooperative ownership. Residents were transformed from marginalized renters to empowered owners; the spirit of the neighborhood was preserved.

But there are three certainties in New York: death, taxes, and gentrification. Despite the decades of struggle (and the victories), Goldin and the committee couldn’t stop City Hall. As CUNY political science professor Frances Fox Piven says near the end of the film, “the harms done by Robert Moses shrink if you compare them to the harms done by Mayor Michael Bloomberg in the 21st century.” The melting pot has been scrubbed to mediocrity, local mom-and-pop institutions replaced by chain stores, tenement blocks by glass towers. And because Rabble Rousers was shot pre-pandemic, ghosts of the area’s very recent past abound, like Gem Spa, a beloved newsstand and counterculture hangout at the corner of Second Avenue and St. Mark’s Place—which is now a characterless café.

Film still courtesy Kelly Anderson

Such melancholic encounters complicate the otherwise rousing film. But the filmmakers are more concerned with finding hope in the ruins, like the young organizer we meet at the end of the documentary organizing her neighbors into the El Barrio/East Harlem Land Trust. The struggle for fair housing and community identity is one many will recognize, and Goldin’s stubborn optimism, that “if you join together and you struggle hard, and cleverly and persistently, you can win,” is a needed tonic to our current cycle of cynicism.

But most of all, Rabble Rousers is a celebration of what’s possible when people stand in solidarity to say, “No.” It’s always a radical act, but especially now, in this City of Yes—a city that could do with more rabble rousers like Frances Goldin.

Rabble Rousers: Frances Goldin and the Fight for Cooper Square screens at the Architecture & Design Film Festival in New York on September 25 at 6:15 p.m. It is co-presented by RECORD and The Village Trip. A filmmaker Q&A moderated by RECORD contributing editor Cliff Pearson follows the screening. Visit the ADFF website for screening information and tickets.