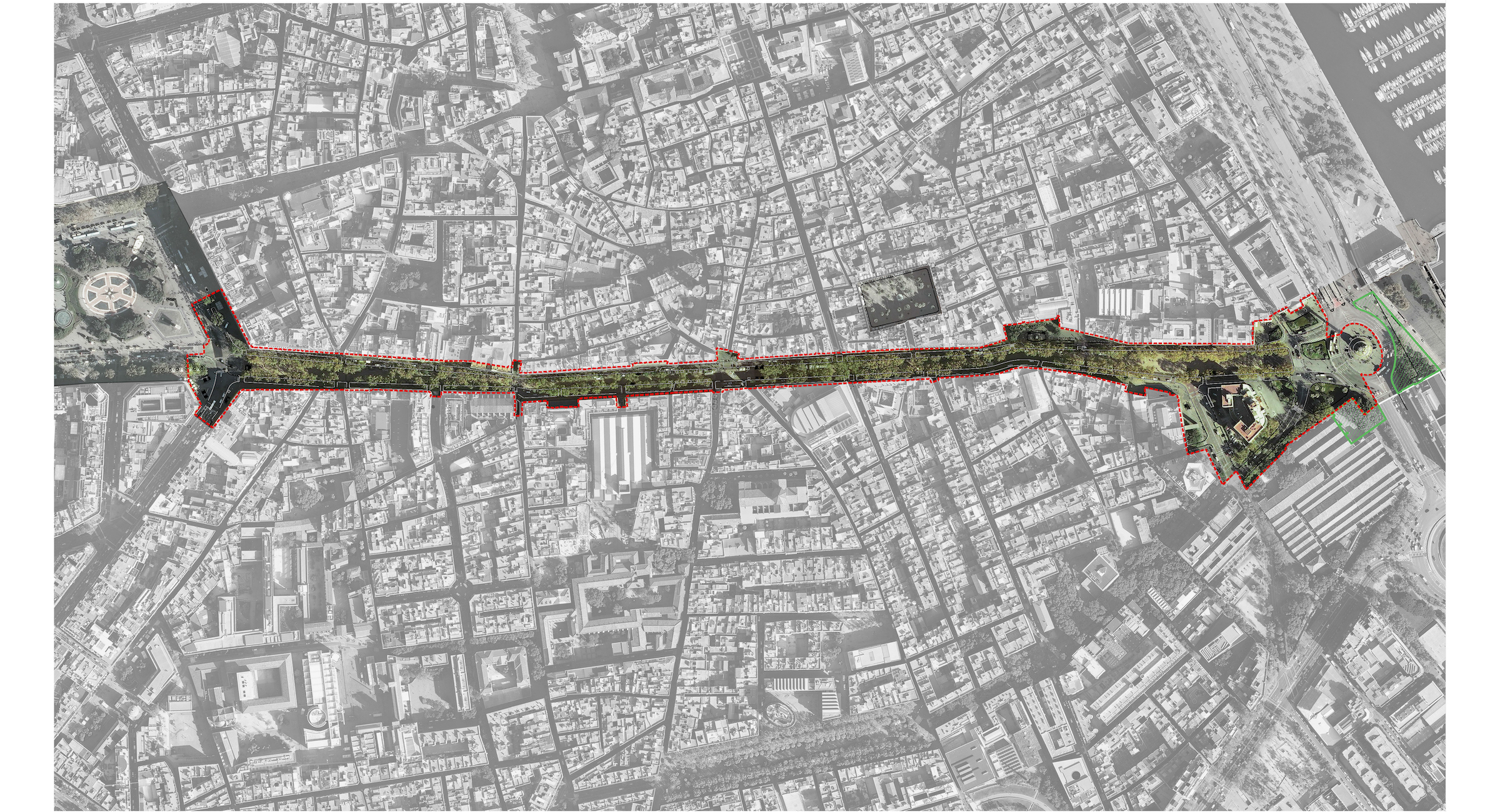

Barcelona’s storied La Rambla—a series of short streets often collectively referred to as Las Ramblas—stretches for nearly a mile from Placa de Catalunya to the Mirador de Colom and the Mediterranean Sea, bridging the narrow, warren-like streets of the old city to the rationalized grid of urban planner Ildefons Cerdà’s Modernist architecture–studded Eixample district. Annually traversed by nearly 80 million individuals (overwhelmingly tourists), La Rambla has, in some respects, turned its back on city residents. Subject to haphazard planning and maintenance over the years, the famed pedestrian boulevard has also grown rough around the edges. In 2017, the city government hosted a design competition for a set of guidelines and plans to return La Rambla back to its rightful grandeur. Km_ZERO, a 15-member multidisciplinary team, with the input of dozens of community groups, won the competition, and now, the first phase of its proposal, led by architect Lola Domènech and landscape architect Olga Tarrasó, is set for completion in October.

The renovation of La Rambla provides greater accessibility and pedestrian space. Photo © Barcelona Turisme

La Rambla has long been in a state of flux. The strip was originally a stream—ramla, in Arabic, translates to sandy riverbed, a linguistic remnant of Spain’s days as a center of the Islamic world—dividing the medieval walled city from its north-east environs. The expansion of Barcelona’s fortifications in 1377 and the subsequent diversion of the watercourse in 1440, transformed the tract to one of the principal axes in the city, hosting an ever-increasing density of cultural, commercial, and religious institutions like the La Boqueria market, the Liceu Theater, and the Church of Bethlehem. The rapid expansion of the city from the middle of the 19th century onward saw the decline of La Rambla as its premier boulevard, ceding ground to Passeig de Gracia and Gran Via de les Corts Catalenes, among others, as it gained somewhat of a sordid reputation for vice. Despite its relative notoriety, the historic thoroughfare remained a vital element of the city, and, following the 1992 Summer Olympics, increasingly metamorphosized into a center for international tourism.

La Rambla runs for just under a mile, from Placa de Catalunya to Mirador de Colom. Image © Lola Domènech

In June, a tour organized by BarcelonaTurisme and Amic de la Rambla, a non-profit organization advocating for residents, shopkeepers, and others tied to the area, highlighted the main issues facing La Rambla in the present day. Former Amic de la Rambla president Fermí Villar led the excursion with Lola Domènech. In less than a mile, the boulevard alternates between around seven different pavement types with the predominant surfacing being cracked and uneven concrete slabs. Dating from the 1970s, one-and-a-half-inch thick concrete was produced in a now shuttered factory. That discordant paving, and its jarring impact on the pedestrian experience, is compounded by two-lane roads flanking either side of the promenade, which is also ringed by haphazardly placed café seating, utility boxes, overgrown kiosks, and other infrastructure. While the jumbled environment is not all too burdensome for tourists who largely stroll up and down La Rambla, it poses something of an obstacle course for residents, who chiefly cross it, going between neighborhoods.

The redesign incorporates nearby streets such as Avenue De Les Drassane. Photo © Barcelona Turisme

The first phase of the redesign is centered on the southern terminus of La Rambla, where it meets Barcelona’s iconic Columbus monument, Mirador de Colom, near Port Vell. This area offers a preview of what can be expected from the rest of the rejuvenation project, which is scheduled for completion in 2027. Most noticeably, the roadways have been cut down to a single lane, a move that provides room for an expansion of the central promenade and adjacent sidewalks. The hodgepodge of paving types, including the asphalt roadways, have been ripped up and replaced with granite slabs, alternating between a gray ochre and red porphyry, to create what Domènech refers to as “a unitary urban civic axis both longitudinally and transversally.” In a nod to the city’s historical evolution, the red porphyry is clustered at boulevard crosswalks and at the sites of the long-demolished medieval gateways.

Bollards line the central promenade and sidewalks for added security. Photo © Barcelona Turisme

The renovation of La Rambla and the stripping of existing paving also provides the design team opportunities for both new landscaping and street fixtures, at this most recent, and future phases. The central promenade is lined with a continuous allée of plane trees, that, with inadequate tree beds and subsoil, are unable to grow to their furthest extent. The removal of asphalt and the expansion of pedestrian space allows for the enlargement of those beds and the installation of additional gravel below grade. The stone-paved roadways, while nearly flush with the adjacent sidewalks and promenade, will be bounded by bollards, some retractable to allow access for emergency vehicles. They’ll be joined by a new uniform street lighting system and approximately 100 benches. Domènech hopes that the redesign, though disparaged by some, like Catalan architecture critic Xavier Monteys, for perceived homogeneity, will “invite pedestrians to stroll along La Rambla, and, at the same time, create new spaces at their feet to reconnect with their historical and cultural heritage.”

The redesign clusters paving patterns around significant historical intersections. Image © Lola Domènech