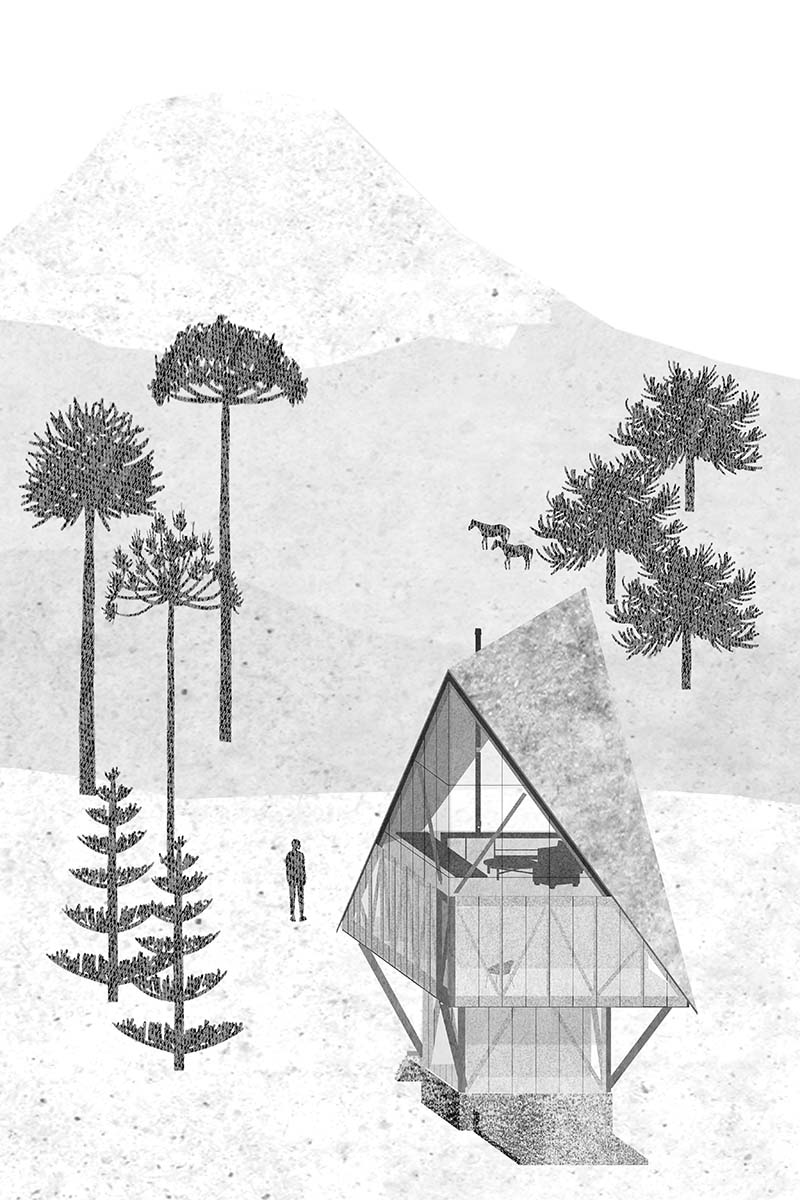

The Ring of Fire, a belt at the edge of the Pacific Ocean where various tectonic plates meet, is home to the majority of Earth’s volcanoes. Chile alone has about a hundred, which dot the Southern Andes to create stunning mountainscapes and vistas. In one such range, architect Max Núñez has designed a weekend retreat for his family. Last month, he spoke with RECORD managing editor Leopoldo Villardi about it.

Tell me about your vacation house. Most often we publish projects that architects design for others. This is a different case.

About a decade ago, we bought a two-acre plot of wooded land between two volcanoes—the Sierra Nevada and the Llaima—near Conguillío National Park. It’s something of an ecological hot spot in southern Chile, with many lakes and valleys. There are raulí and araucaria trees, which flourish in the high altitudes of the Andes. Untouched nature, you could say. It came as a surprise that we could even buy the land. Ever since, I’ve gone camping there in the summer with my wife and daughters.

Photo © Cristóbal Palma, click to enlarge.

I suppose there came a moment when you grew tired of sleeping in a tent?

We love camping, but we always wanted to build a house. Over the years, we got to know the site very well—the landscape, the light, the views. There was a clearing that we liked, with a creek not so far away, where we would always pitch our tents. This is the exact same spot where we ultimately built.

It cuts a striking figure in the landscape, yet is compact and touches the ground lightly. What was the thinking behind it?

I wanted the house to interfere as little as possible with the ground and for it to be vertical, so that you could climb up and get above the understory. The idea was to rest with high-up views of the landscape, rather than stay below the tree canopy.

1

2

Oak lines the living area (1 & 2) and primary bedroom (3), except where there are windows. Photos © Cristóbal Palma

3

Almost like a tree house.

Yes, or a watchtower. Tree houses aren’t as widespread here as they are in the U.S., so I’ve been calling it the House in the Trees instead. But I was also trying to contrast with nature, rather than blend in entirely. The design language is very mechanical and, at the same time, there is still a sensitivity to the place.

The relationship between architect and client is complex—the push and pull can further develop a project, or hamper it. What was it like designing for yourself?

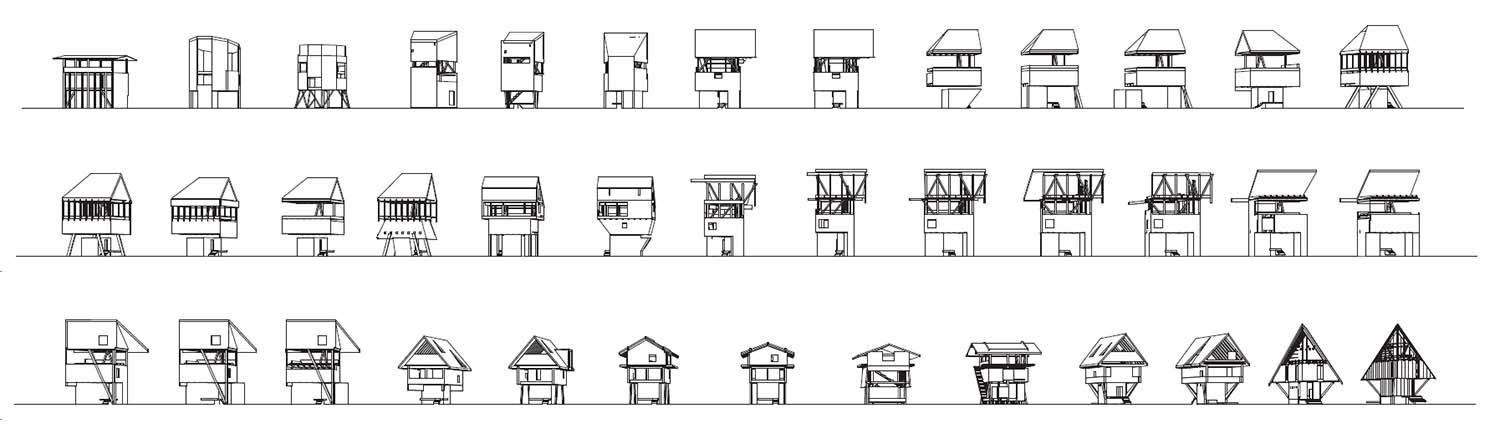

Being your own client is difficult—especially if you obsess over decisions. With another client, the reality is that deadlines force you to stop working at a certain point. You have to make decisions quickly. Here, it was the opposite. Even though House in the Trees is quite small, at about 1,450 square feet, there were about 30 or 40 different early versions.

But the arrangement also gives an architect the opportunity to explore concepts that a client might not be willing to entertain. For example, in this house, there are three different structural systems—one for each floor—an idea that I enjoyed playing with.

I see the bracing holding up the upper stories. What are the other two systems? Walk us through the house.

A vestibule encased by wired glass provides access to the house (above and top of page). Photo © Cristóbal Palma

On the lowest floor, there’s a small entry vestibule—a kind of mudroom—encased in wired glass, where everyone can leave their dirty boots and equipment. It sits at the center of the plan, like a tree trunk. A very narrow and steep stair leads up to the next level, where there is a primary bedroom, two bathrooms, and two small bedrooms. Here, a diagrid at the perimeter braces the building.

On the top floor, there is a living area and a kitchen underneath a kind of A-frame structure. By tilting the roof diagonally, we opened the corners of the plan and broke down the axiality of the space. Here, we also designed a long sofa in a reddish fabric that matches the trees in autumn. The kitchen cabinets and stove hang directly off the steel structure too.

You camped in the summers, but do you use the house year-round?

House in the Trees is completely off grid. We installed a photovoltaic array nearby, which supplies all the electricity we need, and we have a propane system for heat. The plot is only a 30-minute drive from a ski resort called Corralco, which is on the slopes of another volcano, Lonquimay. So, now we’ve extended our trips to include skiing.

How did the site’s relative remoteness affect construction?

The dirt road leading to the house is steep and not well maintained—that was a challenge. But what we like about the plot is that, although remote, it is only a two-hour drive to the city of Temuco. The structural components were fabricated there and then welded on-site. Given the house’s scale, we only needed a boom lift and a small construction team. We didn’t cut down any trees, either.

The aluminum-zinc cladding was crimped and braked manually, which gives the facade of the house a handcrafted quality. All the sharp angles were executed especially well—the metal contractor was able to create very thin and elegant profiles.

We had to take a break from construction, with a winter in between, but once the steel structure was in place, the rest was relatively straightforward. I think it works pretty well—especially once you are up there, more than 20 feet off the ground, and look out to the distant landscape.

Click graphics to enlarge. Images © Max Núñez Arquitectos