Record Houses 2024

A Luminous Residence by Patkau Architects Celebrates the Found Potential of its Coastal Cascadian Setting

Victoria, British Columbia

Architects & Firms

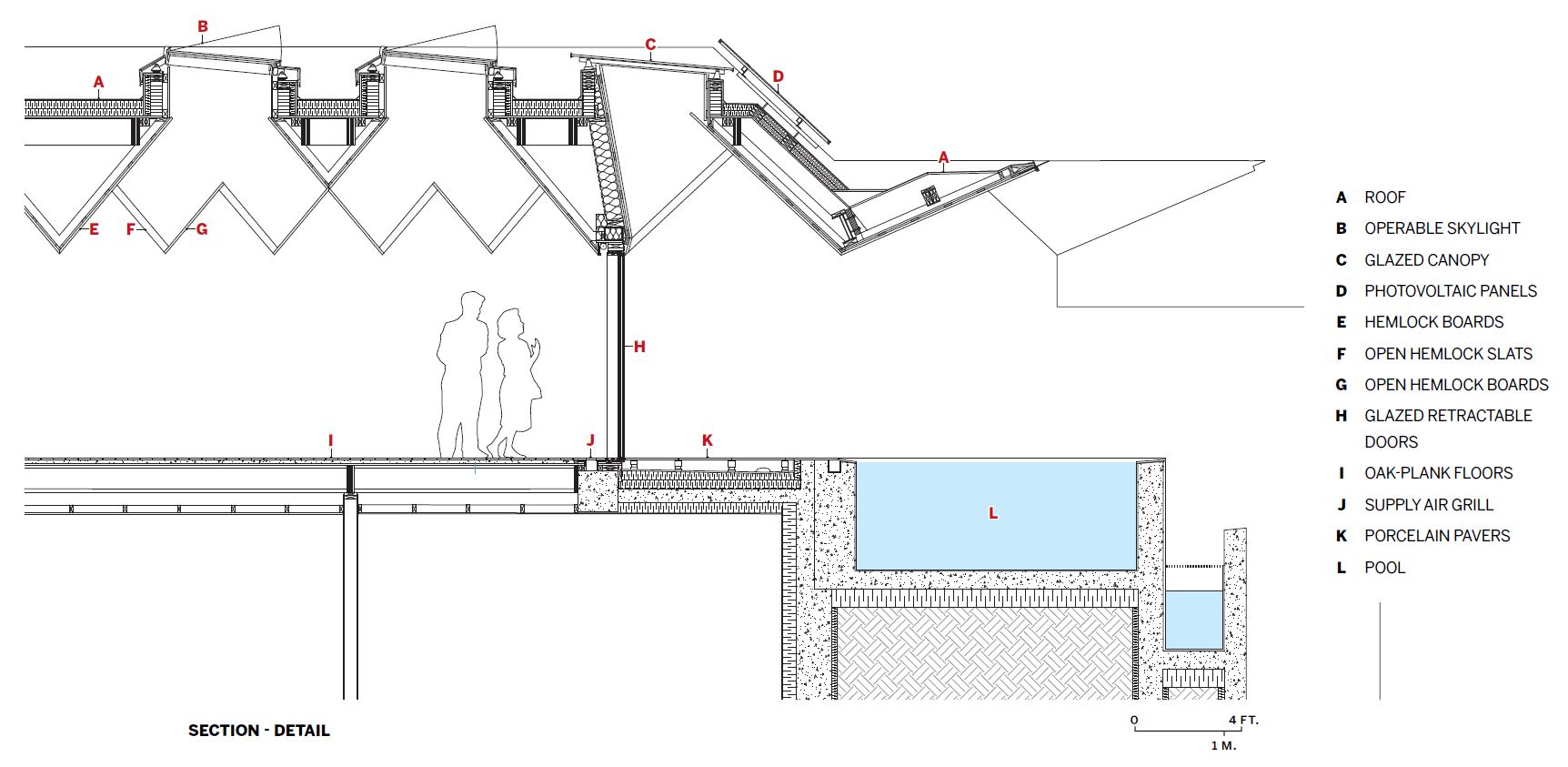

In the living room of Arbour House, a recently completed residence by Patkau Architects in Victoria, British Columbia, sunshine enters through skylights above a folded lattice of hemlock struts and forms patterns that glide slowly across the fireplace wall. Full-height retractable glazing along the front of the house has been drawn aside so that the space flows uninterrupted to a Garry oak–framed view of a bay in the Salish Sea. As the sun crosses the sky, the patterns on the wall eventually vanish, and the space becomes simply luminous. I’m sitting on a sofa in the midst of this—the trees, the water, the light, and air that characterize this city’s connection with its landscape—and I’m wondering if anyone would notice if I just . . . stayed.

Emerging from my reverie, I ask John Patkau, sitting opposite me, if he’d like to say something about critical regionalism. (Architectural historian and critic Kenneth Frampton, who coined the term, has long cited the work of Patkau Architects as an example.) “That’s something that’s always been meaningful to us,” Patkau says. Although to avoid the possible connotation that the firm is defined by a single region, “instead we talk about ‘found potential’ as one of our guiding principles,” he says, “and that means that you look for circumstances of the site that allow you to develop an architecture.” In embodying some of the quintessential experiences of living in Victoria—time by the water, light through the trees, gathering outdoors with friends—Arbour House epitomizes that approach.

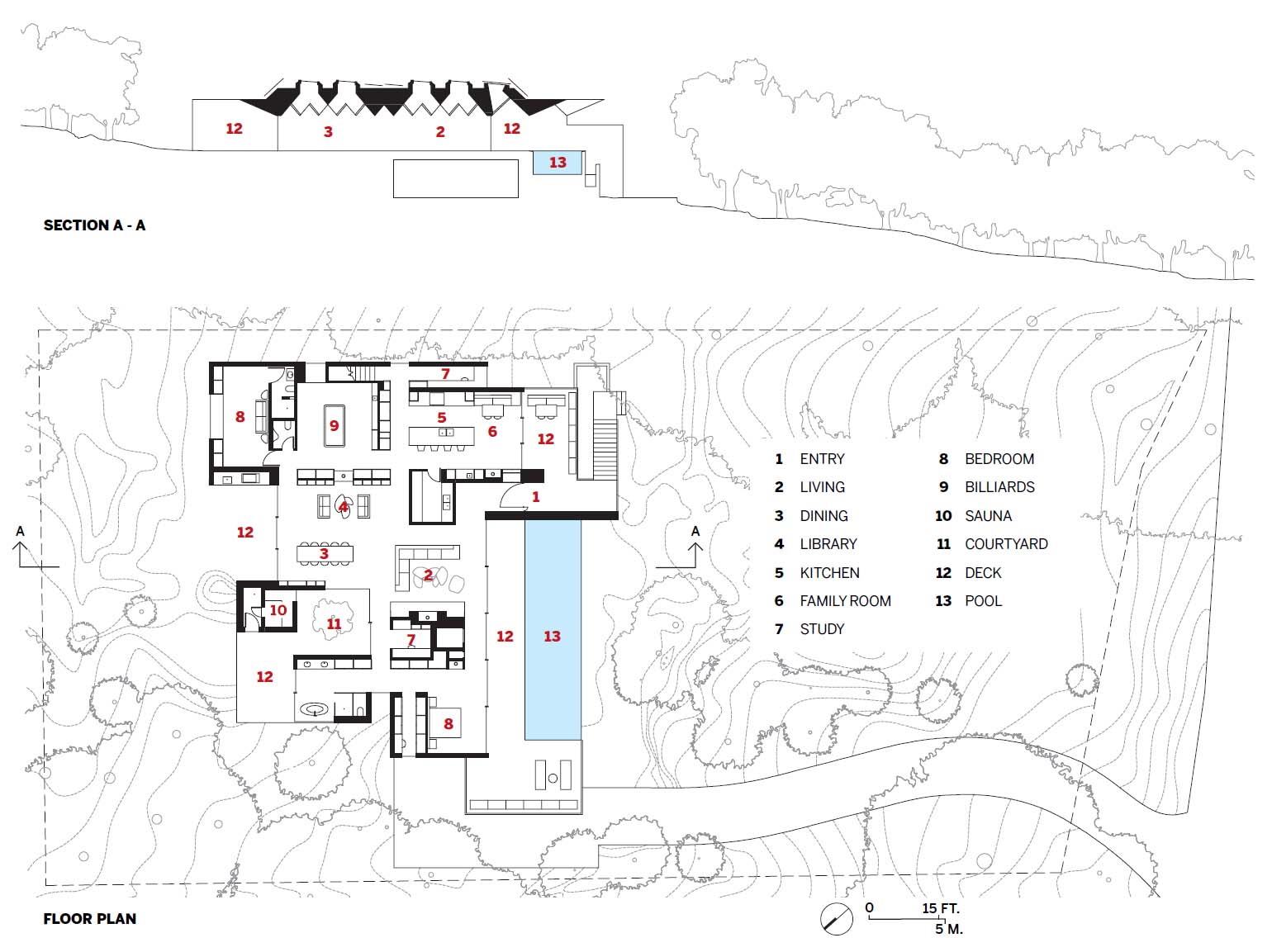

The first challenge the design addresses is to maximize the experience of the water, even though the steep site doesn’t front directly on the bay. The decision to locate the building at the top of the property, instead of nearer to the shore (which isn’t quite near enough), improves its view. And by extending its floor plane forward with a concrete platform that serves as both porch and pool deck, the design blocks foreground views from the interior and creates a direct visual connection with the water.

Rather than being placed close to the water, the Arbour House sits at the top of its steep site, improving its views. Photo © James Dow, click to enlarge.

The concept for the house as “a field under a pergola” responds to the clients’ desire for “an indeterminate indoor/outdoor environment,” Patkau says. The entire 4,000-square-foot, single-story plan is defined by a pleated open-weave wood canopy suspended below arrays of operable skylights. With its varying height and daylit volume above, the canopy in effect elides the existence of a roof. Beneath the canopy, the interweaving spaces of the house flow seamlessly between outdoors In addition to its relationship to its setting, a key aspect of the house is its welcome to sociability. On the one hand, the place needs to feel the right size as a home for just two permanent residents, and, on the other, it must feel generous as a base for gathering extended family and friends. To resolve this paradox, the design employs what the architect calls “a double scale.” Horizontally, the house stretches out, some 96 feet from side to side and up to 83 feet front to back; vertically, it’s compressed, with the low edges of the ceiling pleats defining a datum of just 7 feet 6 inches. “By juxtaposing those two scales,” Patkau says, “you get both intimacy and a sense of expansiveness.”

The living zone isoriented to both the bay and a hillside patio. Photo © James Dow

The layout’s center is a large living and dining zone that opens to both the southwest-facing front and a hillside patio at the back, with a glass-walled courtyard, occupied by a single Japanese maple, bringing nature into the middle. The zone’s seating gathers around Patkau-designed Maitake tables, modular, mushroom-inspired pieces of varying sizes and heights assembled to form multipartite coffee tables. To the east of this zone lies the kitchen; it also faces the water view, opening onto a covered concrete deck with built-in seating off to one side of the main entrance steps. Brighter daylighting than in the living-dining zone expresses the kitchen’s character as a more active, animated space. Also sharing the water view is the primary bedroom, located to the west of the central zone. Here, daylight shimmers on the infinity-edged pool in the foreground, and lamps designed by the architect illuminate the room at night.

1

The main bedroom (1) and the kitchen (2) are among the spaces that share the water view. Photo © James Dow

2

Additional spaces, such as a sauna, billiard room, and guest room, are located along the back of the house, while a garage and guest or caretaker suite (together accounting for an additional 2,000 square feet) are tucked into the slope beneath.

Envelope assemblies and environmental-control systems, informed by 3D energy modeling, prioritize conservation and resilience and further engage the potential of the site. Deep roof overhangs and cross ventilation provide passive cooling; ground-source heat pumps supply heating, cooling, and domestic hot water; and rooftop photovoltaics, comprising 60 335-watt solar panels, generate about three-quarters of the house’s energy needs and charge batteries for emergency backup. Supplementing the municipal water supply, cisterns store well water for irrigation and emergencies.

“Houses are not our normal projects,” Patkau says—the firm has built fewer than 20 in more than 40 years of practice—“but we always treat them as special opportunities. They provide extra latitude to try things that are difficult to do with other projects.” Material Operations, a 2017 book that documents some of the firm’s research into the extraordinary possibilities of ordinary construction materials, illustrates the depth of thinking that has led to the ceiling assembly, for example. It began as an idea for a load-bearing system—an extension of the architects’ research into the intertwiningof wood members to create innovative structures—but for Arbour House it proved more practical to separate the system from the building’s structure, which is a pragmatic hybrid of steel and wood. The exploration may yet find a structural application in a larger work, Patkau says.

On this sunny afternoon at the house, a time-lapse photography session is capturing the movement of the shadows across the living room wall, and I’m pretty sure Patkau and I stumbled through just as the camera beeped. In that sense, for an eternal instant (or until someone deletes that shot from the roll), I do get to stay. Apart from that, it’s time to go. After all, the point of an architecture derived from the found potential of topography, climate, tectonics, and light is surely to connect its occupants with their place in the world, shelter them for a while, and inspire them forward.

Click drawings to enlarge

Click detail to enlarge

Credits

Architect:

Patkau Architects — John Patkau, Patricia Patkau, David Shone, principals; Luke Stern, Marc Holland, Michelle de Jong, Edward Kim, Michael Thorpe, Sebastian Elliot, Nicole Sylvia, project team

Consultants:

RJC Structural Engineering (structural); Margot Richards Lighting (lighting); Haven Garden Design, Red Door Landscaping Services (landscape)

General Contractor:

Rannala Freeborn Construction

Client:

Withheld

Size:

6,000 square feet

Cost:

Withheld

Completion Date:

October 2023

Sources

Rainscreen:

STO

Windows and Doors:

Otiima

Glazing:

Guardian

Skylights:

Velux

Built-Up Roofing:

Soprema

Hardware:

Emtek, RocYork, FritsJurgens

Paints and Stains:

Benjamin Moore, Sansin

Solid Surfacing:

Corian