Newsmaker: Kongjian Yu Says Landscape Is a Matter of Survival

Kongjian Yu. Photo © Turenscape

Kongjian Yu is principal designer at Turenscape, the Beijing-based landscape and urbanism firm he founded in 1998, and dean of the Graduate School of Landscape Architecture at Peking University. He also founded and runs the Turenscape Academy, a non-accredited, hands-on program focused on rural regeneration and located in a small town in Anhui Province. With more than 500 employees, Turenscape has become a powerhouse firm that has designed and built nearly a thousand projects in China and around the world. In 2023, the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum named Yu a National Design Award winner and The Cultural Landscape Foundation honored him with its biennial Oberlander Prize. In 2020, the International Federation of Landscape Architects recognized him with its highest honor, the Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe Award.

RECORD recently spoke with Yu about the role landscape architecture can play at various scales, his engagement with the Chinese government, recent Turenscape projects, and the need to integrate indoor and outdoor environments.

You grew up in a rural community in Zhejiang Province in southeastern China. How did that affect your approach to landscape and design?

For the first 17 yeas of my life, I was immersed in the challenges of living in a small village shaped by its monsoon climate. In the 1960s, Dong Yu village had fewer than 500 residents. It sat along White Sand Creek, which flowed from the mountains through 36 weirs, irrigating the farmland. Seven ponds held rainwater for use during the year, acting as a kind of sponge. During the monsoon, carp would swim up the creek and we would catch them. It was an immersive and intimate experience of nature and community with a range of scales, textures, and proportions that shaped my understanding of landscape. Years later, when I returned, I found my village had been destroyed.

When you left your village, you went to Beijing Forestry University. What did you learn there?

I studied in the landscape gardening program. For thousands of years, “landscape” in China meant “gardening,” usually pleasure gardens for the rich. I began to understand that landscape needed to be the art of survival, especially in a country that was transforming the land with gray infrastructure and in a world affected by climate change. When I returned to China in the late 1990s, my goal was to graft the scientific education I got at Harvard with the wisdom of ancient Chinese farming and water management practices.

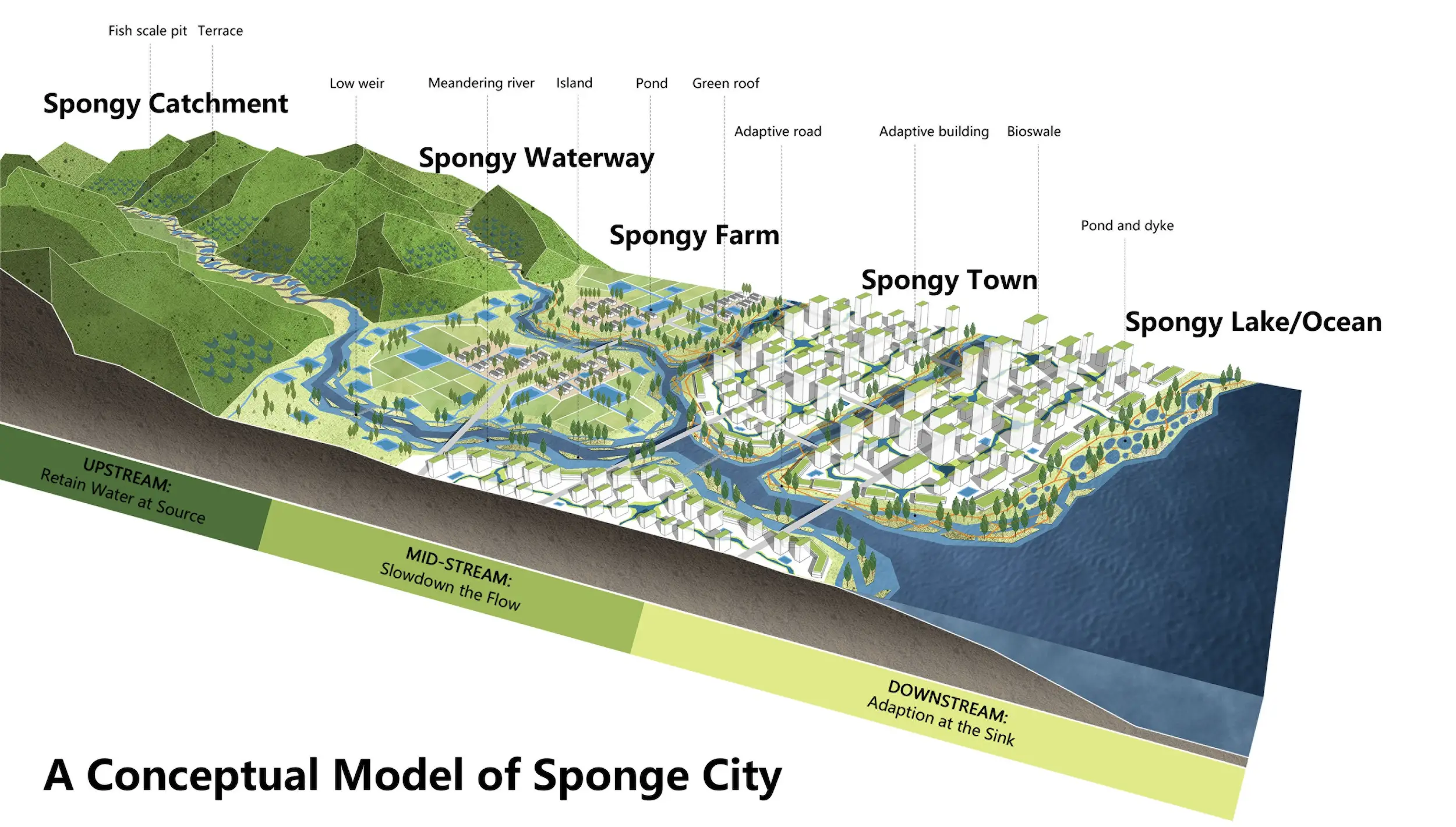

A diagram explaining the sponge city concept concieved by Yu. Image © Kongjian Yu

Explain the main strategies you have developed since then.

Water is the key. Seventy percent of wetlands around the globe are disappearing. We need to manage water wisely. This will reduce temperatures in our cities, recover habitat, and reduce carbon emissions. So, I have developed the concept of sponge cities, which is a nature-based, water-driven, and holistic landscape solution to address climate change. It’s a philosophy that’s the opposite of the conventional strategy of building hard infrastructure like seawalls, river channels, and dams. I’m now scaling up this approach, developing ideas for a ‘sponge planet’ to deal with the ecological crisis we face. We need to work across scales, from regional ecological infrastructure and urbanism to nature-based architecture and down to green walls inside of buildings. We need to create a seamless integration of outdoor and indoor spaces.

Sanya Mangrove Park, Hainan Island, China. Designed in 2015, the 25-acre project won a 2020 honor award from the American Society of Landscape Architects. Photo © Turenscape

You have engaged directly with government in China to spread your ideas. How have you done that?

I have written letters to leaders at all levels of government, from local officials to President Xi Jinping, explaining my ideas for ecological urbanism and nature-based planning. I have given more than 600 lectures to mayors around the country and talked to them about successful projects. In 2018, Terreform published many of my letters along with essays by geographers, urban historians, and critical theorists in Letters to the Leaders of China. I have also written three textbooks for educating Chinese officials. One of them, titled Build Beautiful China, includes a contribution by President Xi. My goal is to use the top-down system of government to change the way cities develop. [According to a recent article in Xinhua, the official Chinese news agency, the nation’s latest five-year plan (2021-25) allocates about $8.4 billion for the construction of sponge cities.]

You proposed strategies to deal with water issues in Xiong’an, the new city outside of Beijing that President Xi began building in 2017 with plans to move much of the capital’s administrative functions there by 2035. Has the government adopted these into their plans?

Unfortunately, no. They’ve only adopted some of the labels—such as sponge city and ecological city.

Yu leads a tour and talk focused on his concept of agrarian urbanism. Photo © Turenscape

You are working a lot now on projects in traditional towns and villages in China to upgrade them and attract tourists. What is driving that?

My goal is to revitalize rural areas with agrarian urbanism, bringing them into the 21st century while retaining their traditional character. High-speed trains and fast internet allow this change to occur, raising the standard of living for the rural poor and attracting digital nomads. I established Turenscape Academy in the village of Xixinan in 2008 as an alternative form of education and a catalyst for rural development. Olmsted made cities more pastoral. I’m trying to make villages more urban.

Benjakitti Forest Park (2022) in Bangkok. Photo © Turenscape and Arsomsilp

Tell us about some of your recent projects.

One of my goals is to do more projects in the developing world where cities need to adapt to climate change and evolve in more sustainable ways. Turenscape recently completed Benjakitti Forest Park, a 100-acre project in the heart of Bangkok that transformed an old tobacco factory into a low-maintenance, regenerative system that intercepts and reduces the impact of storm water, filters contaminated water, and creates habitat for wildlife and a much-needed recreational space for people. Completed in just 18 months, it offers a replicable model for urban engineering that can turn lifeless, concrete-paved areas into resilient ecosystems. I have spoken recently to groups in Indonesia, Vietnam, India, Bangladesh, and Brazil about sponge-city concepts and hope to do work in those places.

1

2

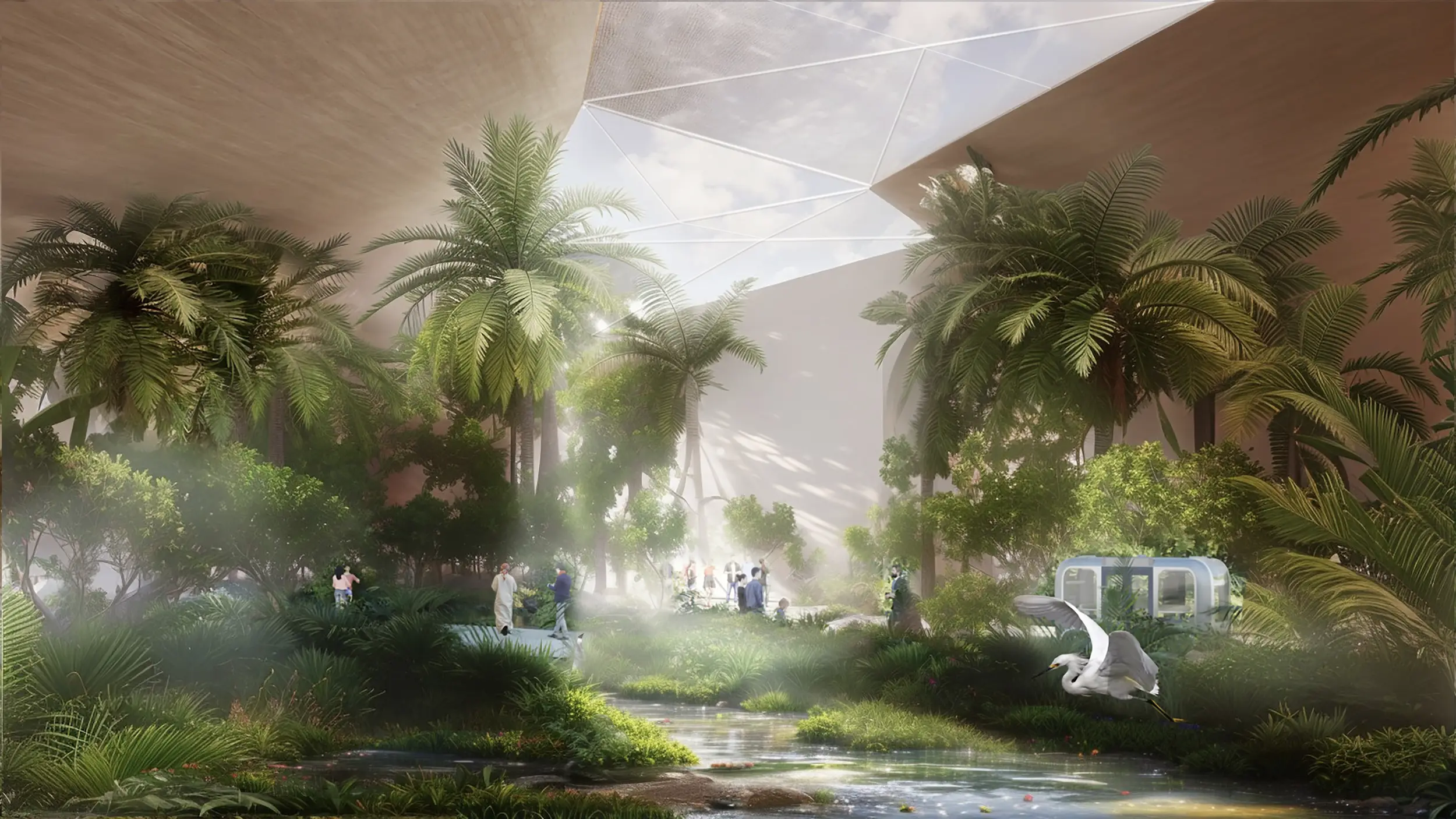

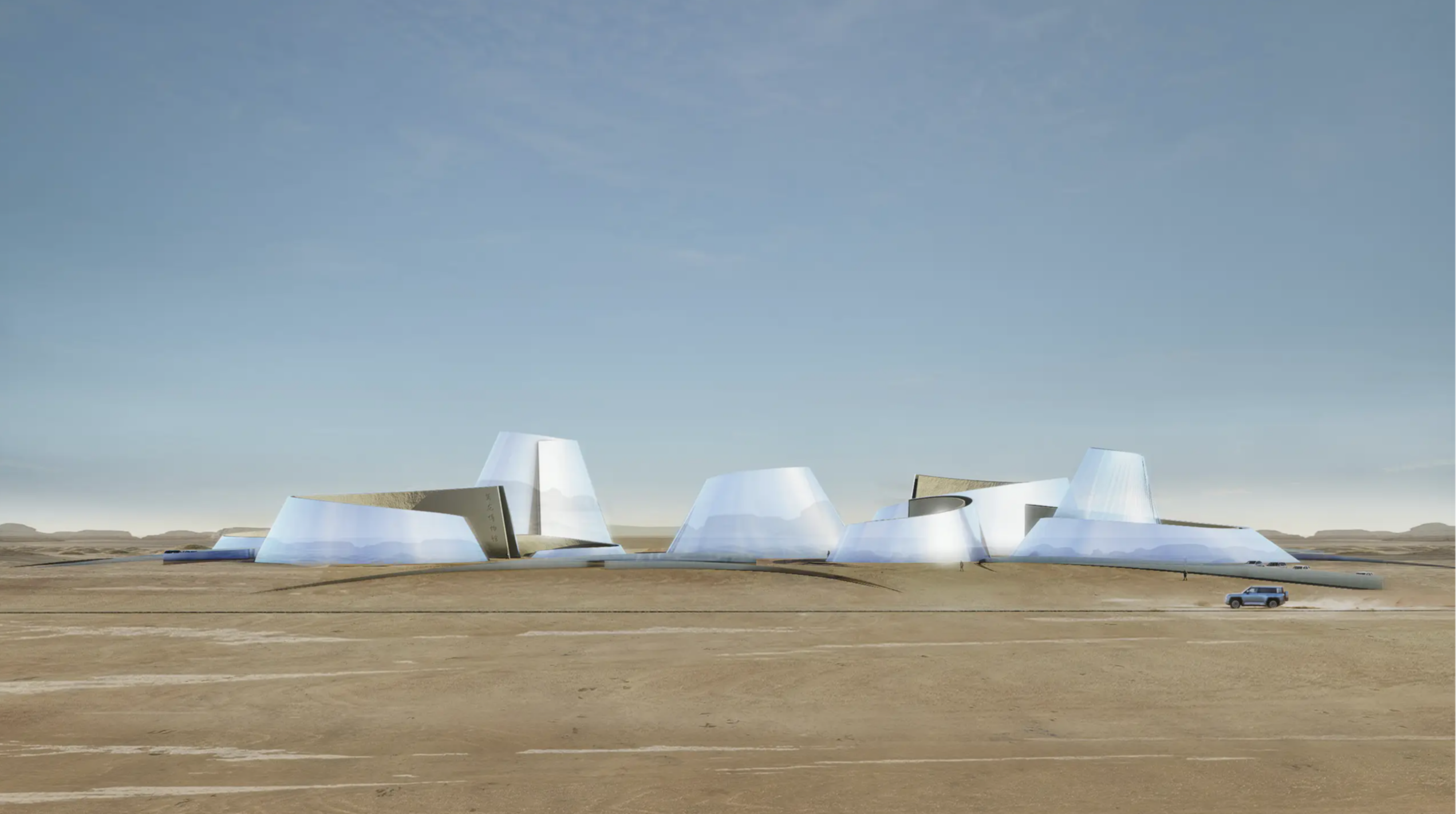

Renderings of two in-progress projects by Turenscape, both in the city of Hami: an underground eco-city (1) and the Museum of the Pterosaur (2). Images © Turenscape

Turenscape is also working on two projects in the desert, in Xinjiang [a province in China’s northwest]. The municipal government of Hami has hired us to design an underground city that capitalizes on local earth forms to reduce the impact on the ecological context while creating a livable environment below the surface. It will be a kind of upgraded Biosphere 2, but with an open system that recycles water and nutrients (waste) and captures solar and wind energy. A second project in Hami City is the Museum of Pterosaur [a series of elliptical forms emerging from the earth].

What’s next?

The landscape architecture profession needs fundamental change, so it can address the challenge of climate change. In just the last few months, there has been unprecedented flooding in Brazil, Bolivia, and China. Landscape must be infrastructure for a new, more sustainable lifestyle.