Architect and writer Pierluigi Serraino, AIA, takes readers on a stroll through Modern gardens in this forthcoming survey, which aims to shed light on the overlooked landscapes that surround so many midcentury masterworks. Bountifully illustrated with striking images by fabled auteurs Ezra Stoller, Julius Shulman, and others, the book explores the (at times fraught) relationships among landscape architecture, building, and photography. Following is an excerpt from chapter three.

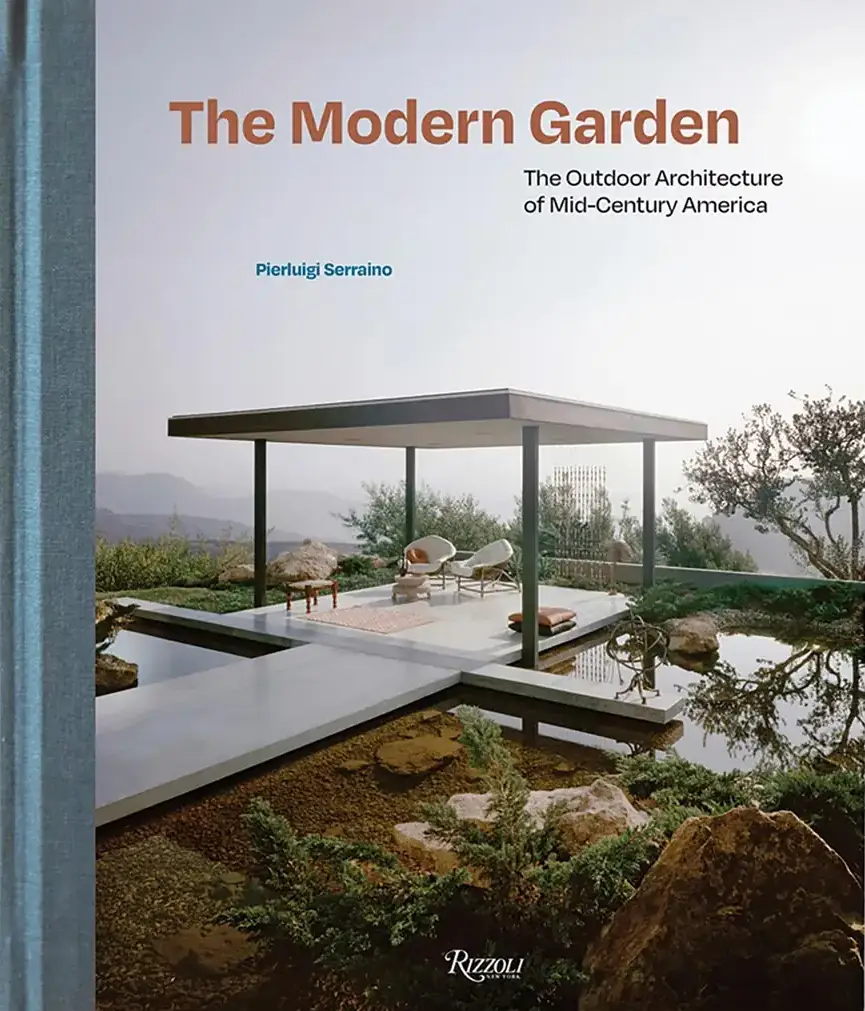

The Modern Garden: The Outdoor Architecture of Mid-Century America, by Pierluigi Serraino. Rizzoli, 224 pages, $70.

Much has been said about the indoor-outdoor connection that Modern architecture opened up. As commonly shared, the directional nature of the connection—that is, from the inside to the outside—reveals the built-in assumption that architecture dominates the landscape. Landscape architects gradually recognized that the reverse was just as viable: outdoor-indoor (that is, from the outside to the inside), thus neutralizing this established hierarchy of architecture over landscape. In the goal of integration, the garden became an open framework to meet ever-changing functional needs, just as architecture was attending to. Garrett Eckbo further expanded these insights: “The landscape must be designed in toto, area by area, precisely because its quality is a direct result of the total combination of all elements seen from a given point of view or circulation pattern.”

With the Gould Garden in Berkeley, California, in the late 1950s, Lawrence Halprin’s vision for the outdoor setting radically transformed the bland character of the residence, which the owner had built a few years prior. As a technical challenge, due to the necessary use of multiple retaining walls, the dramatic drop in height from the entry is solved through a refined cascade of platforms in redwood and concrete, landing on a concrete tray with a six-sided pool inlaid in its boundaries. The circulation was carefully calibrated to deliver the sense of inhabiting an outdoor sculpture where the blend of hardscape and landscape yields a stage set from where to absorb the surrounding vistas. The strong architectonic nature of Halprin’s design puts in crisis the disciplinary divisions of architecture and landscape. The qualitative nature of this open void far overrides the architectural merits of the preexisting structure, demonstrating the latent power of landscape architecture to radically sublimate given conditions into a coherent spatial statement of enduring strength. Such containment of space in the out-of-doors further reinforced the viability of extruding elements of the preexisting structure into a landscape reality existing as a stand-alone experience. The fountain and the scoring motifs on the retaining wall are from Jacques Overhoff’s conception, whereas the pool pavilion is a collaboration with the architect-owner, making this a veritable choral work under a landscape master plan.

In Oakland, California, Beverley David Thorne’s Sequoyah House includes landscape elements designed by Robert Cornwall. Photo courtesy the David Thorne estate, click to enlarge.

While examples such as the Gould Garden increasingly made their appearance in the design vocabulary of the landscape community, architects, for their part, continued to reach out into the garden in their spatial ambitions. Austrian émigré Richard Neutra aimed at grounding his architecture to the specific site in virtually all his residential works. In a seminal article, “The Significance of the Natural Setting” (Magazine of Art, January 1950), he admitted that “the problem may have been narrowed down too much and the structure unjustly segregated from the total impact that it would produce when anchored to its surroundings.” He continued: “For ages, buildings have been designed to exclude the elements to repel the atmospheric influences rather than to absorb them, as organisms do, for the vital process of assimilation and nourishment. . . . While manifestly a foreign body in the landscape, a building can nevertheless be virtually fused with it.” Neutra arrived at these conclusions as a mature architect who had personally witnessed the rapid transitions that Modern architecture was undergoing. His realizations, however, where hardly common in earlier years, or even at the time of that article.

In the relentless quest for a new image for architecture, the challenge for modernists was how to negotiate the fixed image of a reformed architectural space with the changing image of the space of the landscape. The organization of the hardscape took the upper hand in the earlier period, through geometric intricacies, as a form of control to mitigate the unpredictable fluid language of plant materials and the natural flow of walking. Traditional landscape plans frequently offset the geometry of the house into the garden, to replicate spatial relationships on the ground, often at a grander scale. A growing sense of the necessity to set up the environment for landscape to see architecture and for architecture to see landscape progressively took hold among architects. The transparency of Modern architecture called for a far closer relationship to landscape than ever before, its being a see-through invitation to let the environment in. If early Modern architecture had cutouts on its purist walls, then, as decades passed and technologies developed, windows became walls of glass, obliterating that physical distinction between outside and inside for good.