Food, Wine & Hospitality 2024

In France, Philippe Madec Lends a Poetic Touch to an Eco-Responsible Winery

Cantenac, France

Architects & Firms

In a wine-industry peculiarity, the place of production often plays the role of showroom, immersing customers in the making of the merchandise to seduce them into buying. To render the story more compelling, vintners frequently turn to well-known architects, such as Pritzker Prize–winners Norman Foster, Frank Gehry, Herzog & de Meuron, Jean Nouvel, Christian de Portzamparc, or RCR, to name just a few who have tried their hand at wineries. Nowadays, however, not everyone believes in such celebrity branding, as evinced by the new winery at France’s Château Cantenac Brown, 15 miles north of Bordeaux. Here, in the heart of the Margaux appellation, owner Tristan Le Lous eschewed starchitect glitz in favor of French sustainable-building veteran Philippe Madec.

Founded in 1806 by Scotsman John Lewis Brown, the château is located in the tiny village of Cantenac. After acquiring the property, in 2019, Le Lous increased the acreage from 119 to 190, meaning that the old 19th-century winery, located to the north of Brown’s imposing Tudor-style house, could no longer cope with the augmented yield. Flanking the house to the south, a disused hotel from the 1990s seemed like the perfect spot for a new facility, on condition that its fabric could be reused or recycled. “Naturally, I would never have designed this kind of Postmodern facade,” says Madec of the concrete-block structure, with its plaster coating and stuck-on stone dressings. “But it was important to save as much as possible. We incorporated the perimeter walls into our project, and carefully deconstructed the rest.” Crushed concrete became landscape paths, copper pipes went for smelting, while roof tiles and sanitary ware joined the commercial reuse circuit.

The winery is flanked by the château on one side and a covered-market-type structure on the other. Photo © Luc Boegly, click to enlarge.

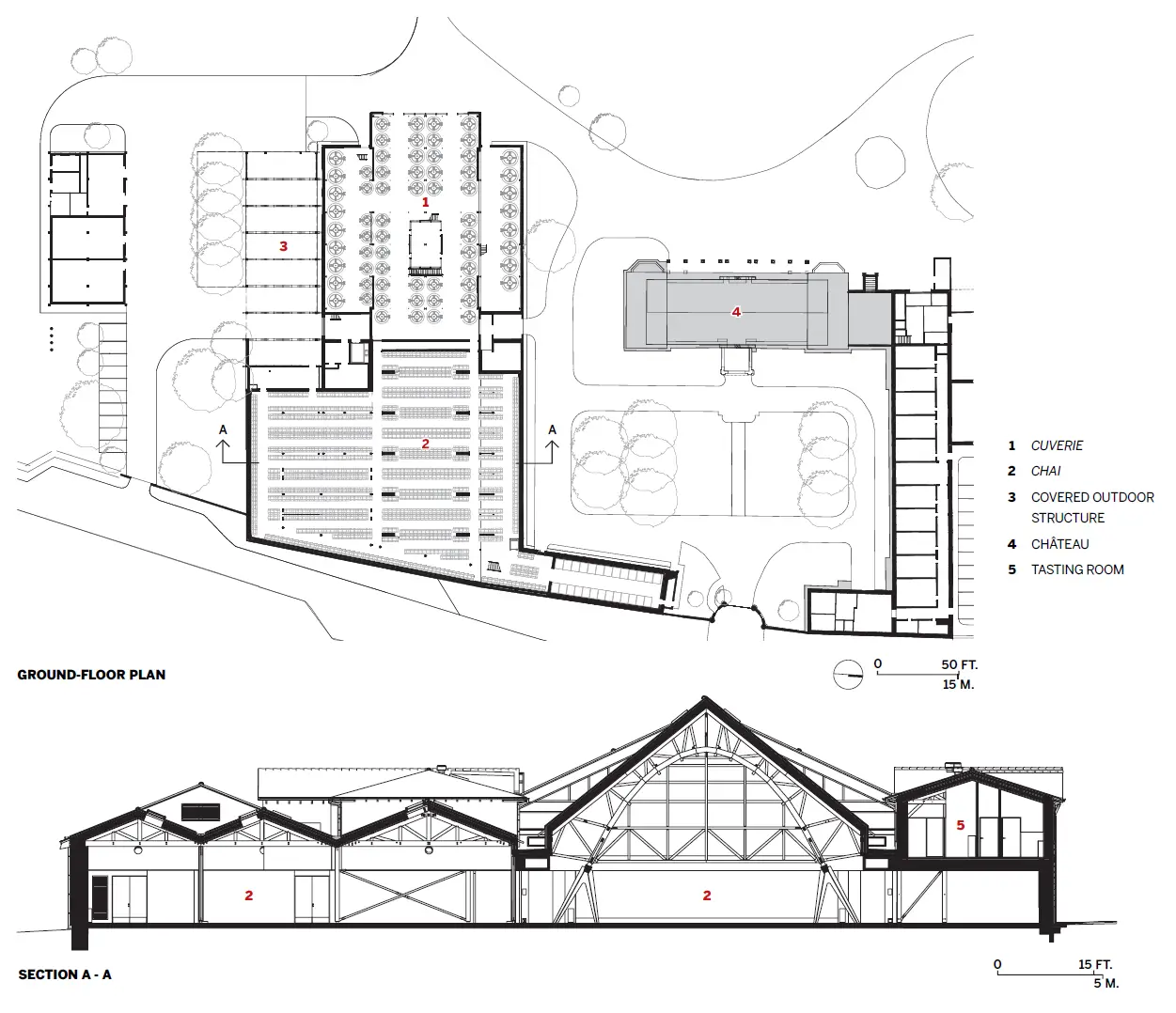

One enters the facility to the south, via a generous covered-market-type structure, open on all four sides, that is used to sort the grapes at harvest time (a task for which many producers simply rent a large tent). Its positioning close to, but not touching, the former hotel ensures a cooling breeze, thanks to the Venturi effect, as air is channeled through the narrow gap at eave level. Detailed with enormous care, the lean timber frame is wind-braced with steel on its hotel side and finished with a nontoxic paint made from flour, linseed oil, and iron oxide, which gives it a distinctive claret color. At the far end, an arched stone entrance leads into the cuverie, or wine-vat hall.

Outside, a wooden brise-soleil protects the glass facade from overheating. Photo © Luc Boegly

Filling the space between the hotel’s two wings, the cuverie is “a place of work, people, and light,” says Madec of this impressive two-story volume. To resist shocks from material handling, as well as the corrosive effects of grape must, the lower part of the structure is in galvanized steel, above which rises a complex wood attic frame whose play of triangles helps keep the roof low in relation to the neighboring buildings. Daylight floods in through generous skylights and to the fully glazed western elevation, which overlooks the English-style park behind Brown’s house. Outside, a wooden brise-soleil protects the glass facade from overheating.

1

2

A complex wood attic frame rises above the cuverie (1 & 2). Photos © Luc Boegly

The striations of the rammed earth imitate string courses. Photo © Luc Boegly

In the cuverie, where the fermentation process takes place, the stainless-steel vats maintain the must at the required temperature, so the building itself need only ensure human comfort, achieved without heating or cooling in part because of the wood-wool insulation and the hotel windows, which open for cross ventilation. In the chai, however, where the wine is matured in oak barrels, a temperature of 15 degrees Celsius (59 degrees Fahrenheit) and stable humidity must be maintained year-round. To achieve this, Madec turned to traditional techniques, building layered walls 3 feet thick: on the exterior, 1½ feet of regionally sourced rammed earth rising on a bed of locally quarried stone; next, 8 inches of cork insulation; after that, a 2-inch air gap; and, on the interior, a skin of unbaked mud bricks, stabilized with quicklime to resist shocks. Located to the east of the cuverie, with one facade on the road bordering the château, the chai presents bare rammed earth to the outside world, its subtly striated surface animated by streaks of claret iron oxide that imitate string courses.

Inside, the transition from the cuverie, “a place of people,” as Madec puts it, to the chai, “a place of wine,” is quietly theatrical. After crossing a 1½-foot-thick timber partition, insulated with wood wool, the visitor enters a dark, narrow corridor, whose other wall is in rammed earth. A door at the far end opens into the chai, guaranteeing a gasp of surprise as one arrives in a soaring vaulted space, dimly lit by rose-tinted slit windows in the far distance. “Heat will rise, so the height helps maintain a steady temperature,” explains Madec. “It also expresses the majesty of the wine matured here.” Constructed entirely from straight members, the wood vault curves upward as a result of the changing lengths of its successive pieces. As in the cuverie, the timber superstructure is supported on steel, in this case claret-painted Prouvé-style splayed columns. Since it came into service, in September 2023, the chai has maintained the desired atmospheric conditions without any need for cooling, but it is connected to a Provençal well in case of extreme heat. (Also known as a Canadian well, this is a passive system that uses the nearly stable temperature of the earth to condition ventilation air in buried pipes.)

At the far end of the chai, a processional oak-and-steel stairway leads to the wine-tasting room, on the second floor of a small 19th-century building at the entrance to the château. “You need light to appreciate a wine’s color,” explains Madec of the sudden transition from gloom to bright daylight as one arrives in a space that is plain to the point of artlessness, with its oak floor and walls finished in milk tempera. Thanks to the generous fenestration, visitors understand they have come full circle, both physically and metaphorically, since the room looks onto Brown’s Tudor-style house on one side, and the château’s vineyards on the other, stretching out to the horizon. Combining method, logic, and a touch of poetry, Madec’s eco-responsible winery forms a contemporary foil to the historic home, which now accommodates Cantenac Brown’s VIP guests.

Click drawing to enlarge

Credits

Architect:

(APM) Architecture & Associé — Philippe Madec, principal

Engineers:

Ingérop, C&E Ingénierie, Le Sommer Environnement

Client:

SCEA Château Cantenac Brown

Size:

99,000 square feet

Cost:

$21 million

Completion Date:

September 2023

Sources

Doors:

EMAM Menuiserie, Atelier D’Agencement

Raised Flooring:

Atelier D’Agencement

Acoustical Ceilings:

Laudescher