A First-Ever I.M. Pei Retrospective Opens at M+ in Hong Kong

I.M. Pei with Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis at Fragrant Hill Hotel’s opening in Beijing, 1982. Photo © Liu Heung Shing

This may sound odd coming from someone who grew up in New York City, but my first immersive experience with modern architecture came when I moved to Ithaca. For three of the four years I spent in that isolated upstate New York town as a student at Cornell University, I was a docent at the school’s Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art. The building, designed by I.M. Pei and opened in 1973, was often called the “sewing machine” for its uncanny resemblance to one, with its thick base, shaft to one side, and cantilevering upper floors over the base. I didn’t know what to make of it at the time, only that I loved being inside of it.

Rendering of the Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art. Image by J. Henderson Barr

The Johnson Museum is among a narrow selection of Pei’s buildings featured in an exhibition—the first retrospective of the architect—that opened in late June at M+ in Hong Kong. An early drawing for the Johnson Museum shows an unrealized plan for a tunnel cutting through rock beneath the building, leading to the edge of the gorge above which the towering structure presides and offering stunning views to Cayuga Lake beyond. It’s a fascinating detail for those who know the building, and the locale, and even for those who don’t.

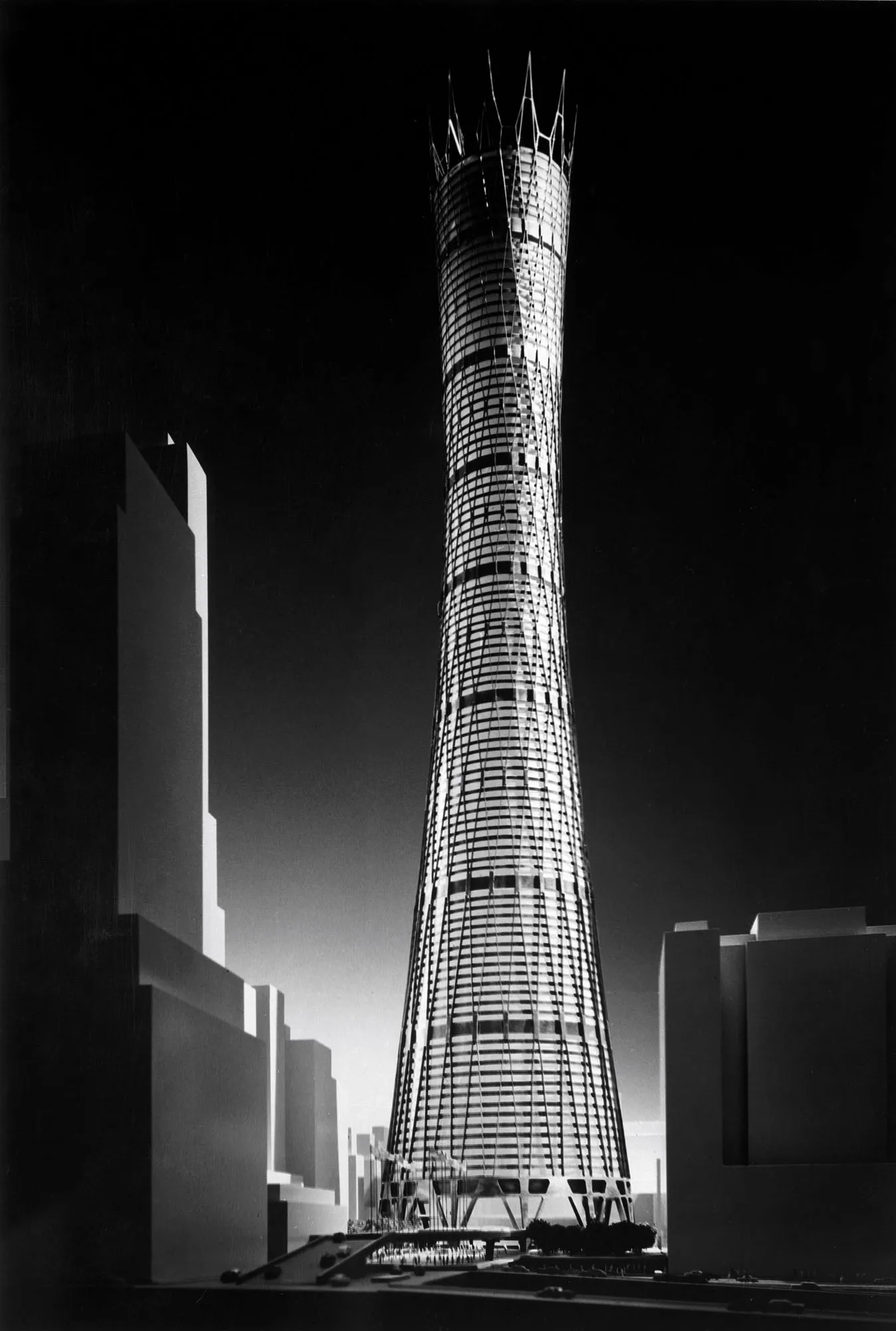

As an architect who designed many acclaimed works and whose career spanned 60 years—from when Pei joined William Zeckendorf to head the architectural division of giant real-estate-development firm Webb & Knapp in 1948 to the design of his last project, the Miho Institute of Aesthetics Chapel in Japan in 2008—it is, after all, his unrealized work that is most surprising. Take, for example, Pei’s proposed scheme for La Défense in Paris (1971) or the Hyperboloid, Pei’s first skyscraper design, from 1956. The 108-story tower was meant to replace Grand Central Terminal. (Plans for it were fortunately abandoned, in 1958.)

1

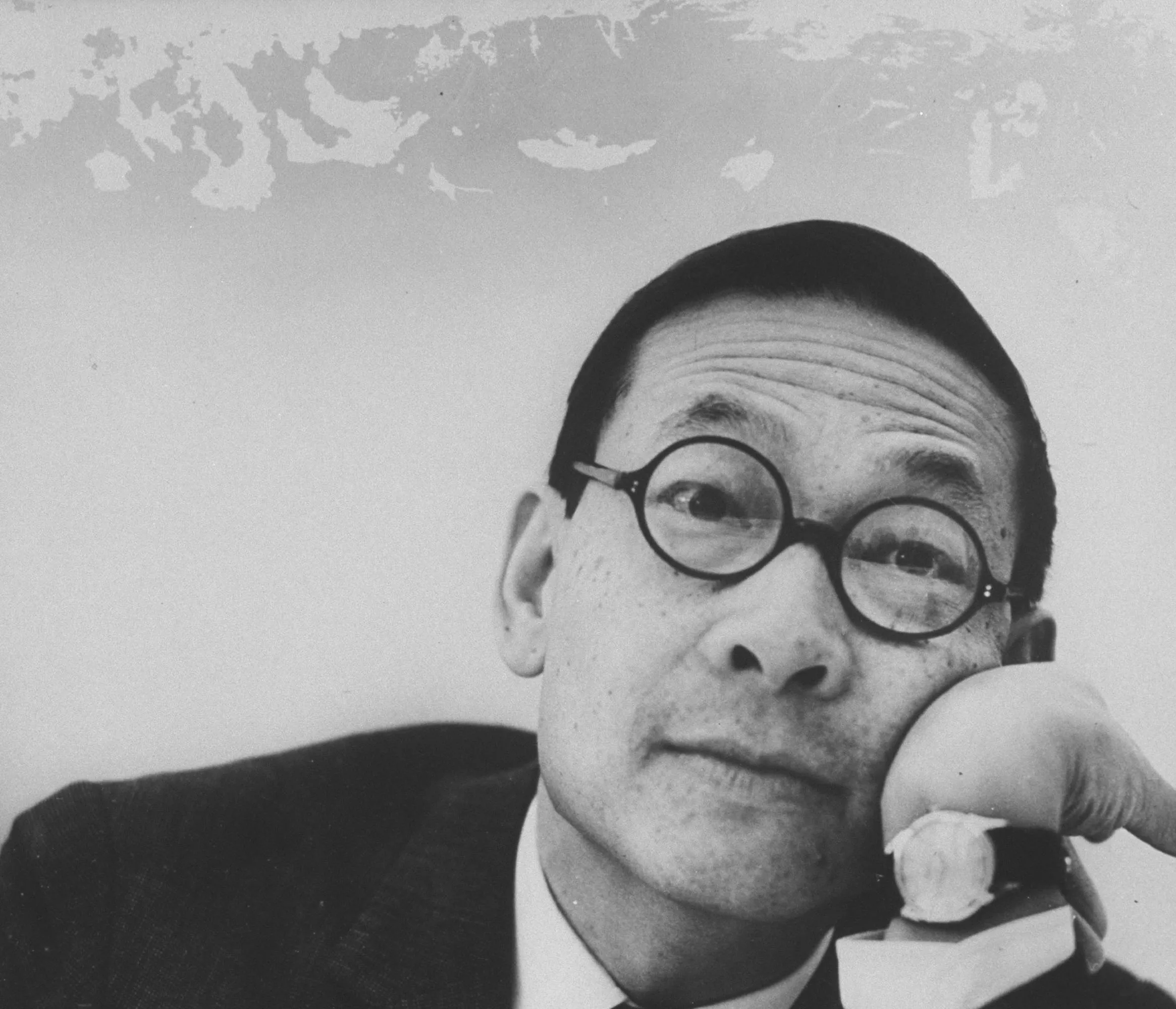

Portrait of I.M. Pei taken when he was selected to design the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in 1965 (1). The unbuilt Hyperboloid (1956), Pei’s first skyscraper design (2). Images © John Loengard/The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock (1); courtesy Pei Cobb Freed & Partners (2), click to enlarge

2

I.M. Pei: Life is Architecture, which runs until January 5, 2025, covers Pei’s long career and famously long life. The curiously organized exhibition, separated into six sections that have several of the projects appearing repeatedly, spans a sprawling 17,000 square feet of gallery space within Herzog & de Meuron’s superlative museum building in the West Kowloon Cultural District. Before Pei died at the age of 102, in 2019, he was approached by then M+ architecture and design curator and RECORD contributing editor Aric Chen, and tentatively gave his consent for a retrospective at the institution, after reportedly refusing one for years.

3

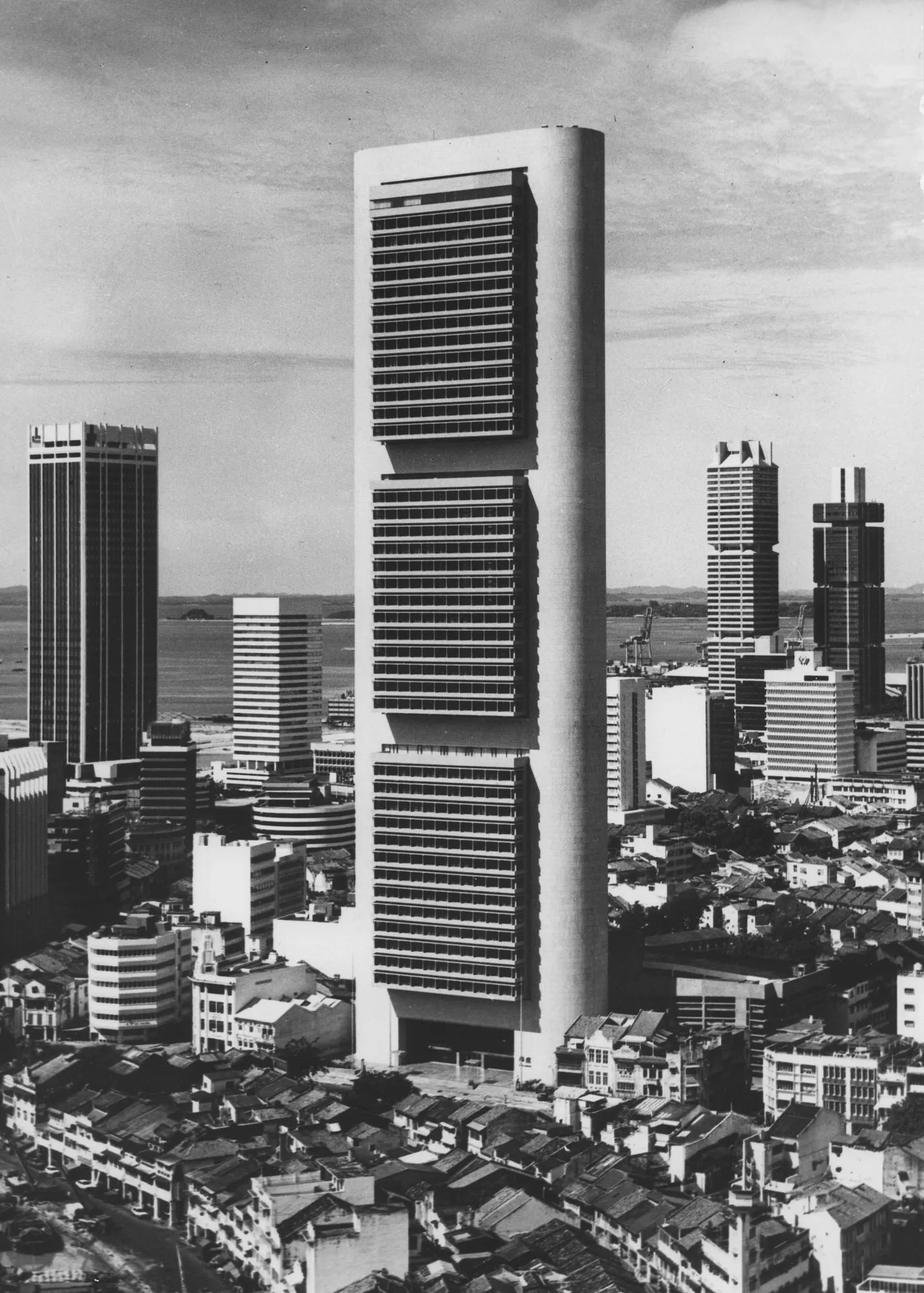

Museum of Islamic Art (2008), Doha (3). OCBC Centre (1976), Singapore (4). Installation view of exhibition showing Bank of China tower in Hong Kong (4). Photos © Mohamed Somji (3); BEP Akitek (4); Dan Leung (5), click to enlarge

4

5

Hong Kong is an apt location for the exhibition—Pei’s family relocated there in 1918, after Ieoh Ming was born in Guangzhou the previous year, and it is the site of one of the architect’s best projects, the Bank of China Tower just across Victoria Harbour from M+. That skyscraper—briefly the tallest in Hong Kong and Asia from 1990 to 1992—is included in the show, as are all the hits, like the National Gallery of Art East Building (1978) in Washington, D.C., and Paris’s Grand Louvre, completed in 1993. There are also a couple of less well-regarded works, according to cocurator Shirley Surya, who describes Beijing’s Fragrant Hill Hotel (1982) as not successful; it was called by many a Postmodern building, though Pei rejected that notion. (The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, an outlier in his oeuvre, is not in the show—perhaps the building missed a beat.)

But even the apparent misses become hits. “Villain Turned Hero” read one paper’s headline about Pei’s hard-fought battle to get the Louvre pyramid built. Regarding his Society Hill project in Philadelphia (1957–64), journalists wrote: “No Longer Are They Laughing at Pei Homes,” and “Pei Homes Now Paying Off.”

Pei and French president François Mitterrand at the Louvre. Photo © Marc Riboud

Pei was a celebrity during his lifetime, and the exhibition, particularly a section devoted to “Power, Politics & Patronage,” is chock full of material featuring the architect in the press (including a cover of RECORD) and with famous world leaders such as François Mitterrand and artists including Henry Moore and Alexander Calder. What it lacks is a deeper understanding of Pei’s process. The section on Material & Structural Innovation, which showcases, among other things, various concrete forms Pei employed, is where I hoped to see more information about his partners, Harry Cobb and James Ingo Freed, and collaborators like Les Robertson.

“This isn’t a show for architects,” said Surya during its opening days. The absence of sketches is startling even if the kind of detailed drawings or analysis of process I expected could be a turnoff to a general audience. Aside from drawings by Pei’s hand from his student days at MIT and Harvard, there is a tiny hand-drawn parti for the Louvre pyramid, but not much else. “He would make a very simple sketch, one or two lines, and then sketch on top of other people’s drawings. It was a very iterative process,” said Pei’s son Sandi, who worked with his father on the Bank of China Tower, and who was also present for the exhibition opening. (Sandi’s brother Didi, with whom he ran PEI Architects, died unexpectedly in December 2023.)

Installation view, I.M. Pei: Life is Architecture. Photo © Wilson Lam

Despite some shortcomings—in part due to scant materials, according to Surya, at Pei Cobb Freed & Partners’ offices (note to architects about preserving their archives)—the exhibition is a worthwhile look at a sometimes underappreciated figure, his Pritzker Prize notwithstanding. Pei was never accorded the same reverence as his contemporaries Louis Kahn or Paul Rudolph (whose unusual blue-walled double office tower, Lippo Center, sits across the road from Pei’s Bank of China building in Hong Kong). Adds Sandi Pei about his father, “He wasn’t a provocateur.”

Pei was, instead, the envy of many architects for the sheer number of buildings—icons, even—he completed (perhaps even the envy of Kahn, against whom Pei won the commission for the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, featured unremarkably in the exhibition). Travel the world and you’ll see his work, in places from Singapore, Beijing, and Paris to yes, even Ithaca. The show itself, set to travel to Pei’s Museum of Islamic Art in Doha in 2026 and reportedly elsewhere, seems executed to fully establish Pei’s reputation for the future. Whether that happens is a question. So far, there are no plans for the exhibition to come to the U.S.