The British Columbia–based firm, hcma architecture + design, has a diverse portfolio spanning a wide variety of building types, from education to housing. But community recreation facilities, especially those focused on swimming, are a major part of hcma’s practice. Standouts include the Hillcrest Centre, in Vancouver, which began its life as the hcma-designed curling venue for the 2010 Winter Olympics, and then post-games, was transformed by the firm into a swimming and multi-sport facility. There’s also the Grandview Heights Aquatics Centre, in the nearby suburb of Surrey, with its striking wavelike roof.

So much so are public swimming facilities a priority for hcma that it created a “pools manifesto,” published as part of a 2013 monograph on its aquatic architecture. “Every site and situation are unique” is the very first of the document’s eight tenets. Now, more than a decade later, the just-completed təməsew̓txʷ Aquatic and Community Centre, at the edge of a residential neighborhood in New Westminster, BC, shows that this doctrine is still a guiding principle. At the project’s heart, is what Paul Fast, hcma principal, calls “a gnarly site challenge.”

Although each of the building’s programmatic zones has its own roof, all are clad in back standing-seam metal. Photo © Nic Lehoux

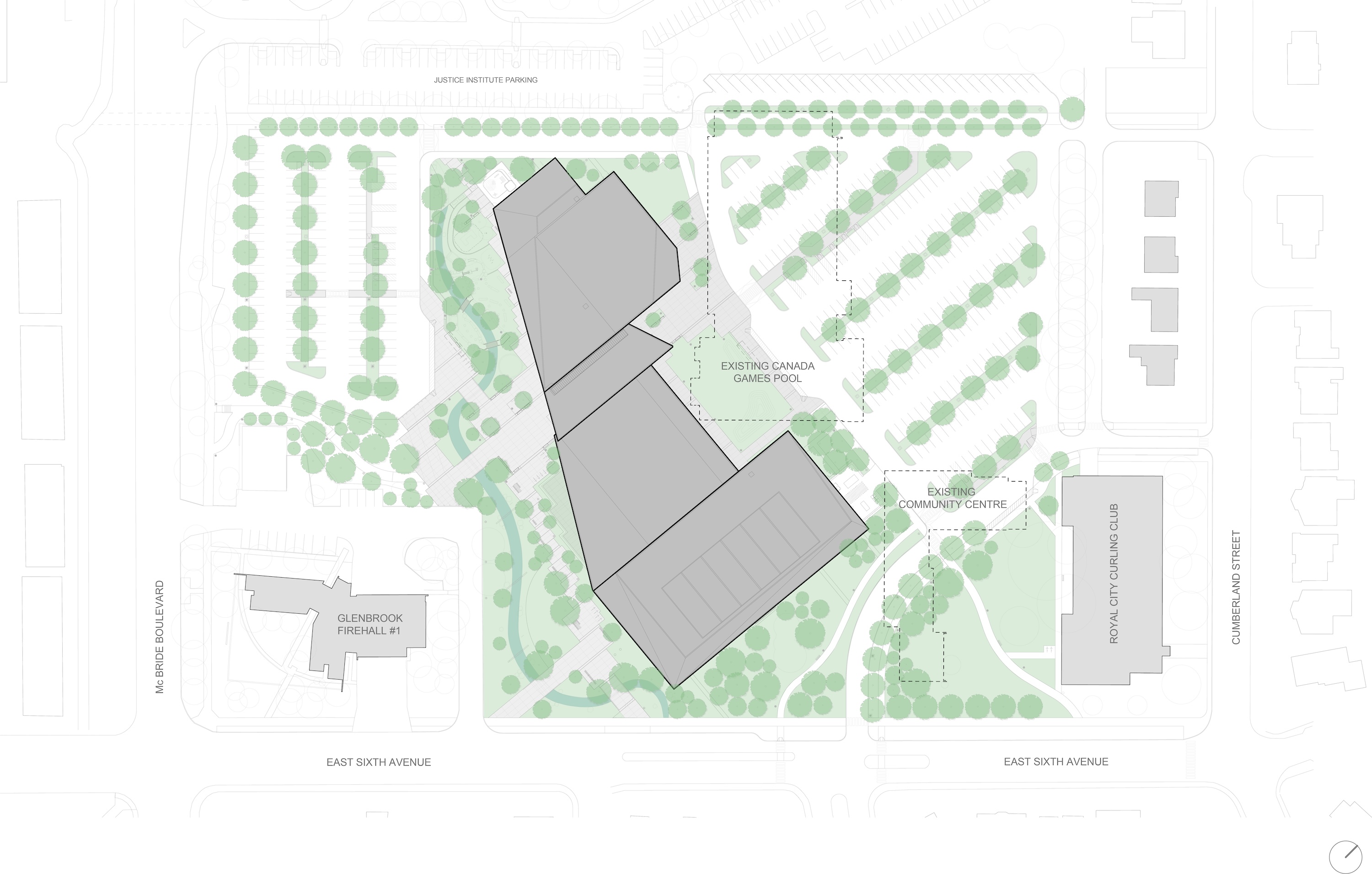

The $83-million təməsew̓txʷ complex, whose name means “sea otter house” in the Indigenous hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ language (for the name’s pronunciation click here) replaces two aging facilities—the Canada Games Pool and the Centennial Community Centre—both about 50 years old. The project brief required that the two existing buildings remain intact throughout construction and that the new facility stay clear of a major sewer line. The solution involved running the 480-foot-long structure at an east-west diagonal on the rectangular site, countering the urban street grid. This strategy also presented an opportunity, allowing the team to restore an important natural landscape feature: a ravine that had been backfilled over the preceding decades due to development. The project creates a public green space while “paying homage to the historical topography,” says Fast.

1

2

The competition-level pool is topped by saw-tooth roof with north-facing skylights (1); the overhanging roof over the leisure pool is partially supported on scalloped, precast-clad piers (2). Photos © Nic Lehoux

Though the facility is large, enclosing 115,000 square feet in all, its scale is modulated with individual but contiguous volumes tailored to the programs within. With the idea of creating what Alexandra Kenyon, hcma project architect, calls “a proud but approachable building,” each zone has a distinct roof, though all are clad in unifying black standing-seam metal.

For instance, the most eastern end of the building, housing a competition-level 50-meter lap pool and two diving platforms, is sheltered under a sawtooth roof with a hybrid structure combining steel trusses and cross-laminated timber (CLT). The northern orientation of the skylights reduces glare for both swimmers and the lifeguards, notes Fast. Meanwhile, the adjacent leisure-oriented aquatics area, with 25-meter-long lap lanes, spray elements, and a “lazy river,” sits below its own folded-plate roof of CLT panels and steel girders. To the west, the gyms are covered by a typical metal deck and open-web steel joist system.

The double-story lobby’s sculptural stair leads to second-floor fitness facilities. Photo © Nic Lehoux

Connecting the aquatic and gym zones is the daylight-filled, double-story lobby. Its sloped roof features glulam rafters supported by steel beams. A sculptural spiral stair leads to a second level housing additional amenities, including a fitness center.

The building’s dramatic lobby opens to two plazas—one to the north and another to the south. The northern one, which Kenyon says is “more every day,” allows for informal gathering and for programming, such as yoga classes, to move outside. The south plaza, she describes as more formal. It overlooks the reintroduced ravine and includes a sculpture by Squamish Nation artist James Harry.

3

4

The leisure pool area has a folded plate roof of CLT panels and steel girders (3); the gymnasia are sheltered with a typical steel joist and metal deck system (4). Photos © Nic Lehoux

In addition to its dual entrances, the building has other features that make it especially porous to its surroundings. One example is the leisure swimming area which opens out onto a south-facing patio through large folding glass doors. Even the changing rooms— which include all-gender options as well as dedicated male and female spaces—offer a view corridor through the 25-meter pool to the outside. This visibility makes the spaces safer, says Kenyon, noting that it is a deterrent to theft from lockers.

The south entry plaza includes a sculpture by James Harry, a Squamish Nation artist. Photo © Nic Lehoux

The təməsew̓txʷ facility, which is all-electric, is the first completed aquatic center certified under the Canada Green Building Council’s Zero Carbon Building-Design Standard—a significant achievement for a typology that has historically been an energy hog. The building complies with an early version of the Zero Carbon guidelines, which focused almost wholly on operating carbon, deploying such strategies as optimal orientation, a high-performance envelope, and energy-conserving systems. It also includes a rooftop photovoltaic array that meets about five percent of the energy demand. The remainder comes from the grid, which in this part of world depends primarily on hydropower. “The premise,” explains Fast, “is to bring down the loads as much as possible, and then supply the rest with fossil-fuel-free energy.”

5

6

The changing rooms feature a view to the leisure pool and the ravine landscape beyond (5); lobby skylight detail with views to multipurpose studio (6). Photos © Nic Lehoux

The architects say that təməsew̓txʷ is also the first municipal pool in North America to use an innovative European filtration system by InBlue which relies on gravity, cutting pump energy consumption by nearly 50 percent. The system also uses UV disinfection, reducing the need for chlorine and minimizing the creation of its noxious chemical byproducts, making for improved air and water quality.

This forward-thinking building infrastructure should help the complex enhance the health and well-being of New Westminster residents for decades to come. But just as critical to the success of təməsew̓txʷ is its embrace of the landscape, its civic presence, and its human scale.

Click site plan to enlarge

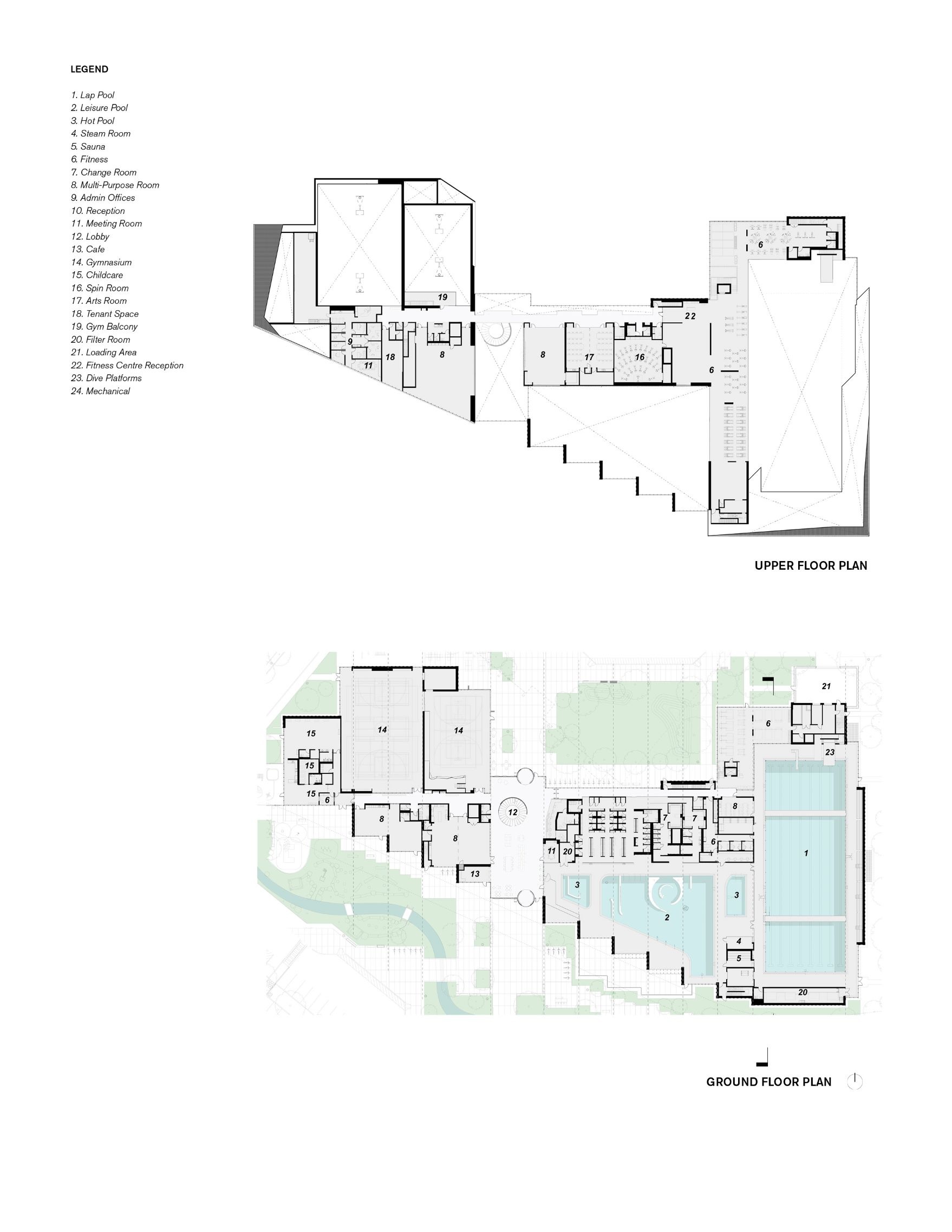

Click upper and ground floor plans to enlarge