There’s a core tension in midcentury American Modernism between authenticity and commercial exploitation. Its most talented adherents were idealists whose work was so good that they became celebrity architects of a world we still occupy. Our buildings, products, even corporate logos all bear Modernism’s fingerprints, or at least DNA. But today much of it is disposable junk and derivative nostalgia, selling a lifestyle aesthetic rather than true craftsmanship.

Commercialism clearly won. And no one person is responsible. But writer-director Jason Andrew Cohn's documentary Modernism, Inc.: The Eliot Noyes Design Story, opening in New York on July 19 and in Los Angeles on August 9, locates Boston-born architect and industrial designer Noyes at the center of the conversation.

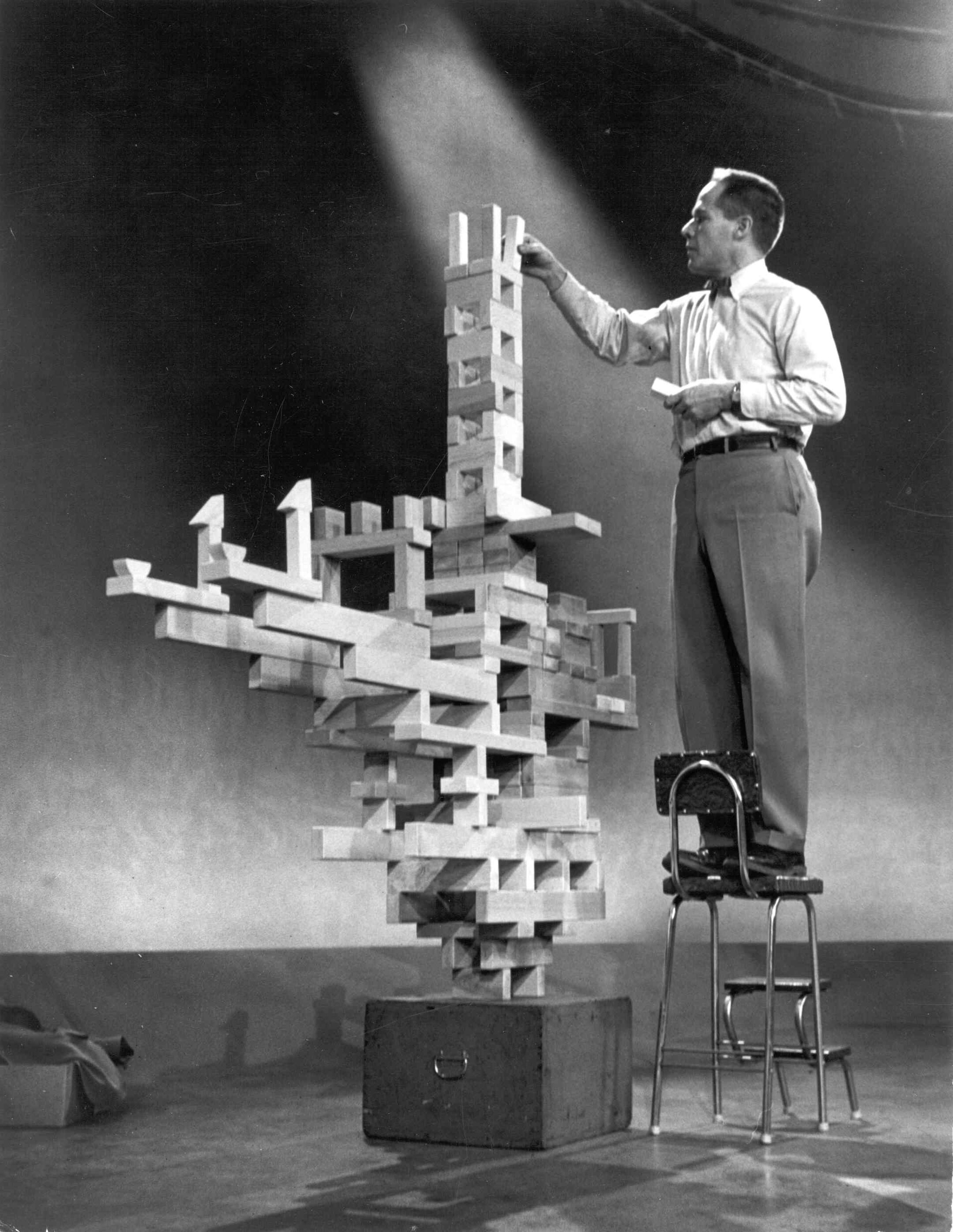

1

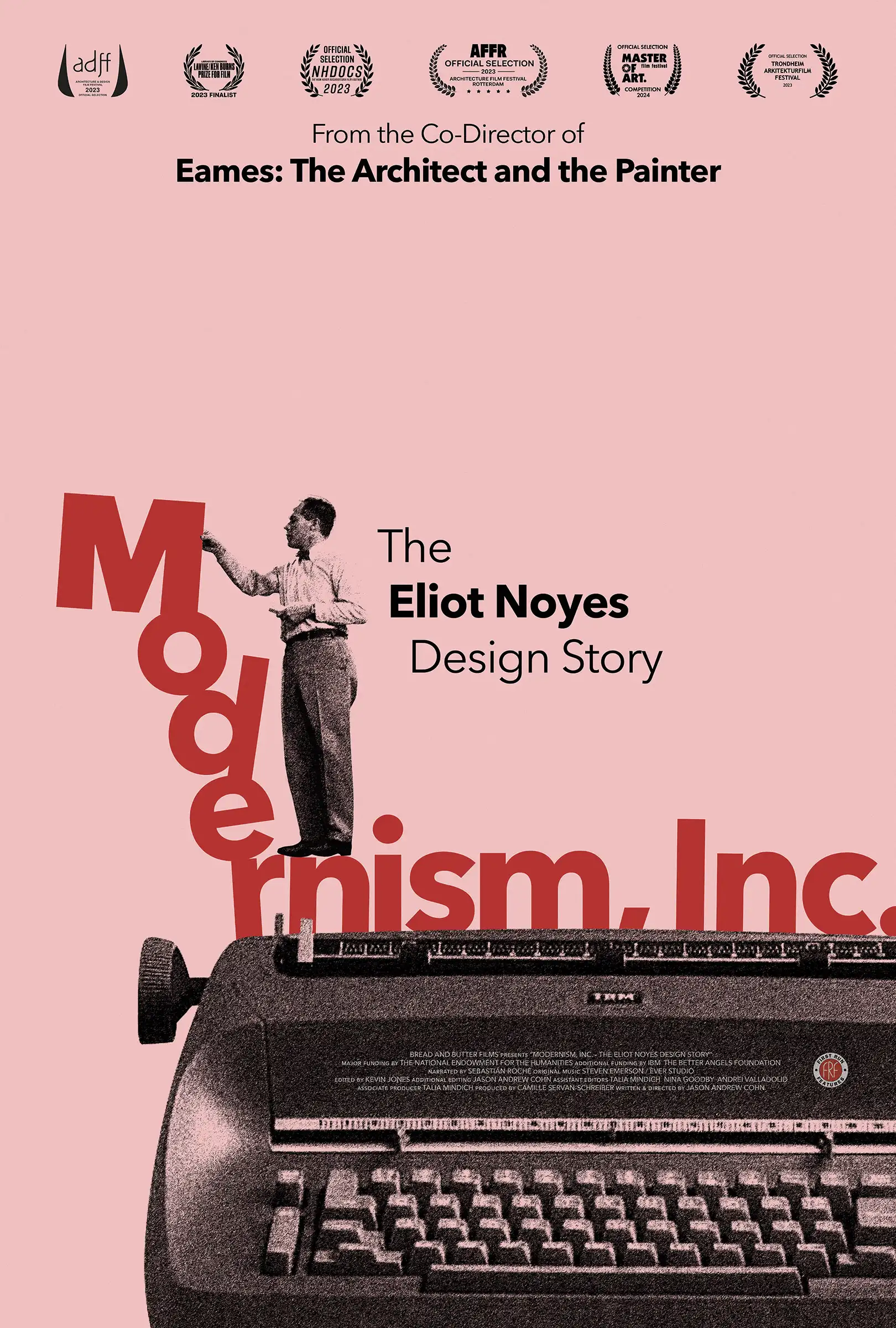

2

Noyes giving a lecture on the TV program Omnibus; (1); poster art for Modernism, Inc. (2) Photo courtesy the Noyes Family (1); image courtesy First Run Features (2)

The film is brisk at 79 minutes. Cohn, who previously co-directed Eames: The Architect & The Painter (2011), tosses out ideas and arguments—about Noyes and his work; postwar consumer capitalism; the Noyes’ legacy, and Modernism’s—for us to chew on long after the credits roll. But he rarely dwells on anything, particularly when it comes to Noyes enabling, even unintentionally, a corrosive culture of corporate primacy.

It’s a tricky needle to thread. Noyes indeed embodied the best and worst of Modernism. His idealistic goal of improved relationships between people and products, and people and nature, is omnipresent. It’s there in 1940 when, as the Museum of Modern Art's first curator of industrial design, he mounted "Organic Design in Home Furnishings,” a provocative confrontation between overdesigned American stuff and elegantly functional (and minimal) European products. It’s in the homes he designed in New Canaan, Connecticut, which were inspired as much by the Bauhaus as the natural surroundings. And it’s in his work as IBM’s consultant design director, dragging the company out of prewar obsolescence into the postwar vanguard with the Selectric typewriter and a rebrand that still guides the company.

.webp)

Eliot Noyes served as consultant director of design for IBM from 1954-1977. Photo courtesy the Eliot Noyes Family

But Noyes' mantra was "good design is good business.” And his embrace of Modernism in service to IBM—and Mobil and Westinghouse, among others—helped global corporations seed and perpetuate a multigenerational addiction to overconsumption. Noyes wanted better, simpler interactions between humans and machines, be it a computer or a can opener. Corporations just wanted people's money. As his son, the late Eli Noyes, says in the documentary: "You did this in a pure, thorough, clear-sighted way, carving out a life, a purpose, in the middle of a kind of corrupt American postwar society that was clearly going in a different direction than we wanted to go."

The struggle between ideals and distortion flares throughout Modernism, Inc., most emphatically at the 1970 International Design Conference in Aspen (IDCA). What was meant to be a sedate gathering of designers and corporate executives discussing "Environment by Design” became a fiasco. A group of hippies, pranksters, and long-haired activists crashed the party and directly, furiously confronted the middle-aged IDCA squares about their role in environmental degradation. In the aftermath Noyes, then IDCA president, argued that maybe the conference should evolve to meet changing times. The group responded by voting him out.

During Noyes’ time with IBM, he helped revolutionize the design of computers. Image courtesy IBM

In another documentary, one more skeptical of the corporate imperative, this episode would frame the narrative. But Modernism, Inc. allows too much deference to the “Inc.” of its title. The film clearly sees Noyes, who died in 1977 at 66 years old, as a key enabler of the commercial takeover of Modernism—“Modernism-lite,” as a design historian puts it—but it also clearly doesn’t see that as a problem.

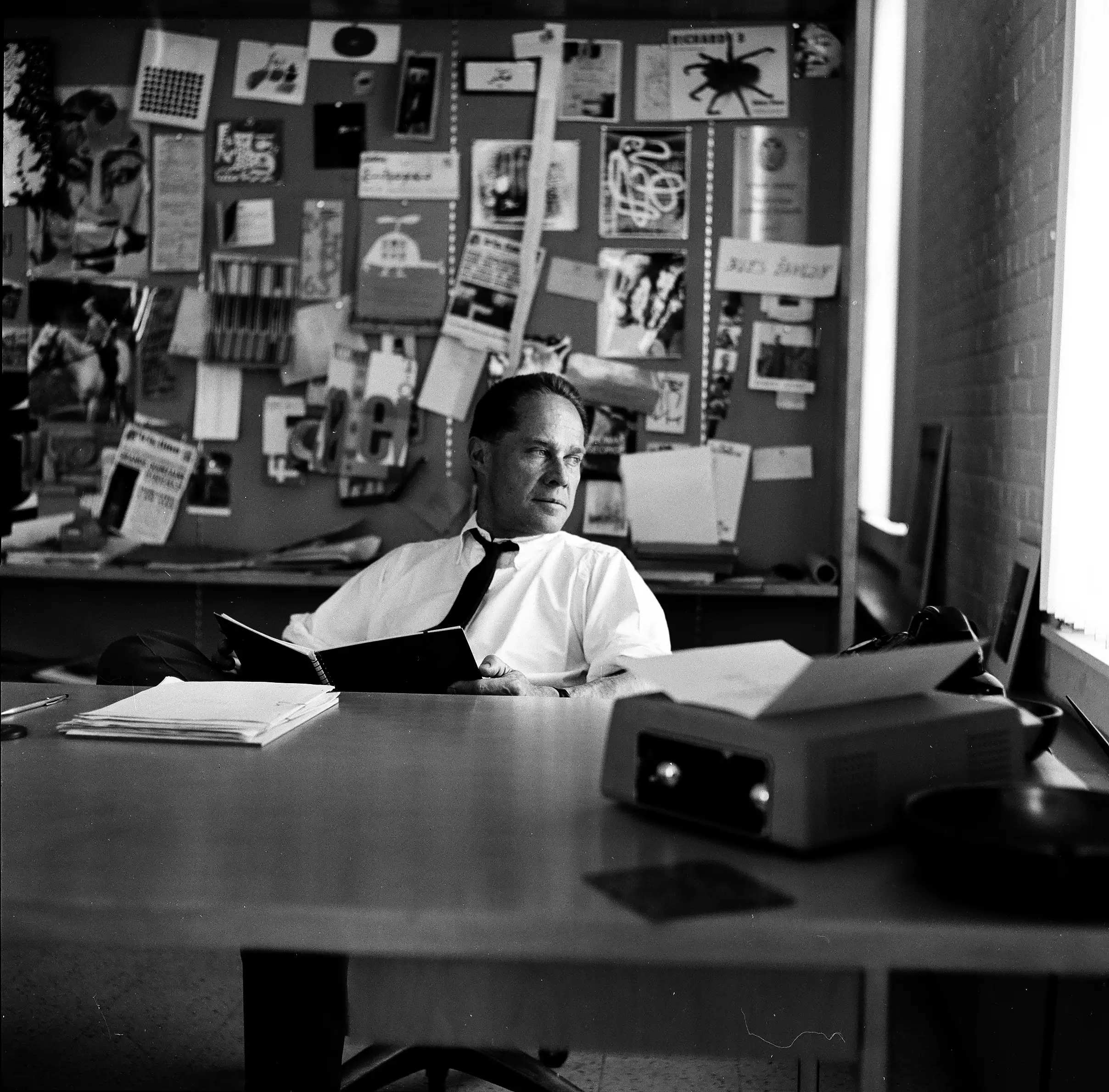

Eliot Noyes at his office in New Canaan. Photo courtesy of the Eliot Noyes Family

Throughout the film, Noyes’ multifaceted design story is told by historians and academics; people who worked with him; his children, friends, and antagonists. None are naive about his complicated legacy. Yet the final word—the literal closing statement of the film— belongs to Todd Simmons, IBM's vice president of design and brand experience. "It was the role of creating and crafting the character of the company into everything that is his greatest contribution," he says. Noyes' ideas for home-building or dynamics between humans and objects or the coexistence between people and nature are all secondary to corporate synergy.

Something tells me that’s not what Noyes meant by “good design is good business.” And it undercuts an otherwise engaging, albeit flawed documentary. Noyes is a fascinating thinker, designer, person, and his influence is clearly greater than helping corporate America inject itself into every facet of our lives.

At the very least, Simmons’ conclusion deserved some healthy pushback. A 45-second rebuttal wouldn’t have killed the film. But then where does Modernism, Inc. end? Where does the conversation about Modernism’s contested legacy end? As the last 70 years have proved, it doesn’t. It just roils, perpetually, churning up more questions, more debates, more documentaries—and more products.

.jpg?height=200&t=1734636287&width=200)