Landscape

At UT Austin, Snøhetta’s Grove of Towering ‘Petals’ Transforms a Museum Campus

Austin

Architects & Firms

Snøhetta’s exuberant reimagining of the grounds of the Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas at Austin is very much of this moment. Photogenic and selfie-friendly from a thousand angles, 12 sculptural shade structures rise above the museum’s courtyard to create an identity and entrance for one of the country’s foremost university art museums. While visually lighthearted, Snøhetta’s redesign is also heavily considered. The firm’s approach weaves campus aesthetics (red tile roofs, arches, loggias, limestone), weather (an often scorching climate), and assertive neighbors (the domed State Capitol and Austin, Ellsworth Kelly’s rebuttal to it) into a new 20,000-square-foot courtyard that offers dappled shade, rocking chairs, a sound garden, and multiple views of the green triangles of Carmen Herrera’s site-specific mural dancing along one wall of the museum. In doing so, it makes a place where past, present, and future can coexist.

1

Features of the revamped 200,000-square-foot grounds include a public lawn (1), mural (2), and promenade (3). Photos © Casey Dunn, click to enlarge.

2

3

The intervention resolves a struggle that began 23 years ago, when a design for a new museum facility by Herzog & de Meuron was overruled by the UT Board of Regents and replaced with a markedly more conservative design by Kallmann McKinnell & Wood. The Regents-approved design created two buildings—one for the galleries and one for administration—straddling a central courtyard. The new museum buildings fit in so well with the rest of the campus that the gallery was hidden from would-be visitors, who often complained that they could not find the entrance. A design by PWP Landscape Architecture preserved existing historic live oaks that framed a view of the State Capitol from the courtyard but further obscured the entryway.

Still, the Blanton’s then-director, Jessie Otto Hite, and her staff carried on, celebrating the new museum’s opening in 2006 and offering ever more adventurous programming to whoever found their way in. And that might still be the story, were it not for Kelly, who, like a deus ex machina, plunked a secular chapel at the end of the courtyard, throwing whatever was left of PWP’s landscape into confusion. This move, along with a substantial donation from the Moody Foundation in 2019, created the opportunity for something new.

As an architecture student at UT in the early 1980s, Snøhetta founding partner Craig Dykers saw the campus begin to grow beyond its Beaux-Arts loggias. He also saw the university respond to a previous era of student protests and barefoot hippies with the installation of landscape barriers and exposed-aggregate sidewalks. He describes the firm’s approach to the courtyard design in philosophical, if not political, terms: “Knowing how the university has evolved and grown over time, we wanted to shift the identity of the school from a palace of power to a garden of knowledge and expression. Both things have their pros and cons—a certain amount of power is needed to organize things, and too much of a garden of pleasure gets sort of decadent, so we were trying to strike that balance,” Dykers says.

As Matt McMahon, director of landscape architecture at Snøhetta, explains, the team began by “unpacking” the courtyard. The site was as complicated underground as it was above, with immovable vaults, utilities, and easements, along with the root zones of the heritage oaks. First, the design team removed many of the landscape barriers. Surface parking areas were eliminated, creating space for gardens. The designers then drew a straight path from the adjacent parking garage to the museum entrance and let site conditions shape that path into a nearly 500-foot-long promenade that’s as cheerfully acrobatic as the rest of the project: up to avoid utilities, down to avoid tree canopies, and over to avoid easements, sometimes spanning 20 feet or more to protect critical root zones. Meanwhile, on the exterior of the gallery building, an inverted arch framed in yellow indicates the museum entrance and creates a window where visitors can look back over the courtyard to the café and gift shop.

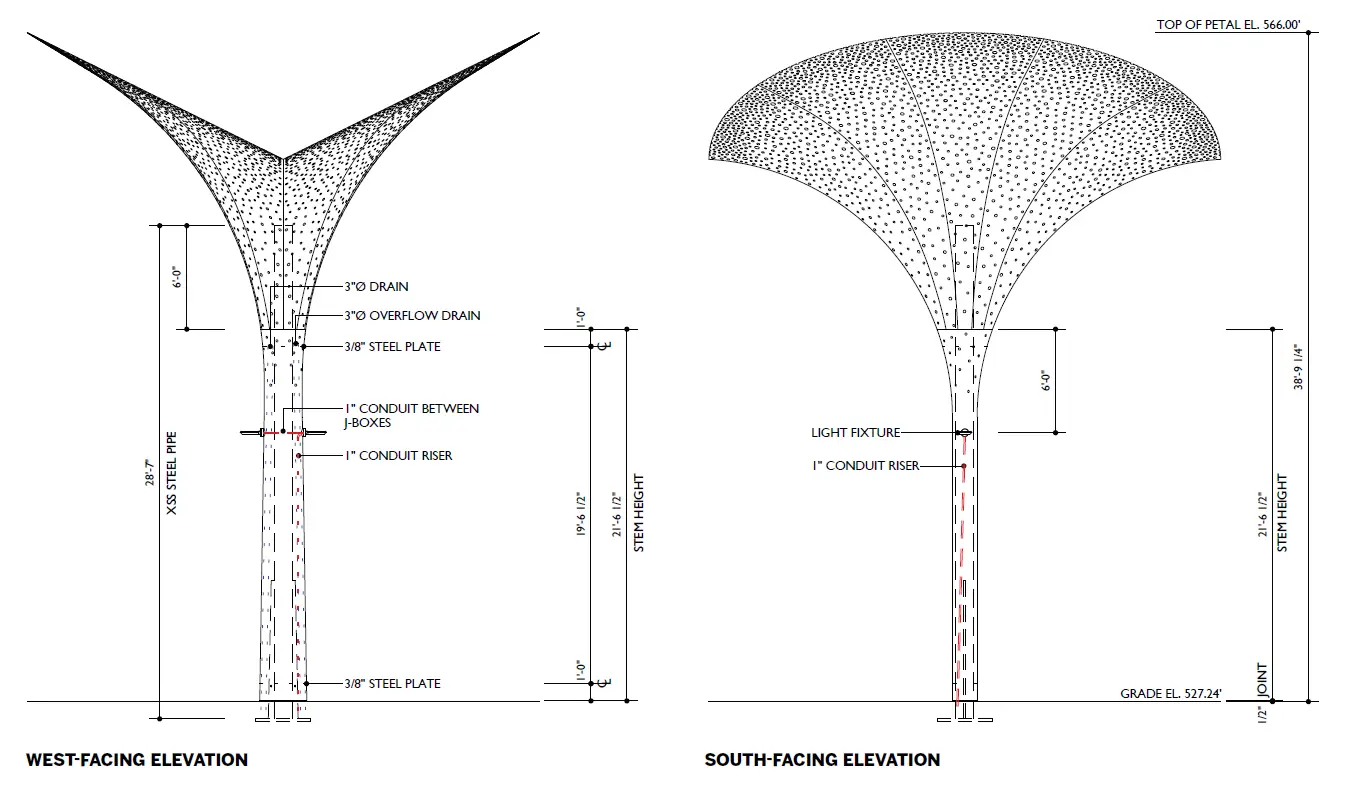

The shade-providing petals stand nearly 40 feet tall, outside a loggia-fronted building that houses the Blanton’s collection. Photo © Casey Dunn

As for the shade structures that populate the courtyard, “They’re doing a lot formally that makes them a curious experience,” says McMahon. Constructed of fiberglass with the help of creative fabrication company Trans FX, the perforated petal shapes rise 39 feet high and span 30 feet in diameter but are still light enough that they don’t require enormous footings. McMahon describes how the team made multiple iterations of the petals, creating full-scale models to test shadow patterns, then creating a digital model to determine the ideal locations for native plantings and seating. The courtyard, once used mostly as a shortcut between classrooms, is now a cool place to linger.

Looking at the petals, you might see arches, or hearts, or circles. With these structures, Snøhetta seems to have taken the surrounding arches and domes—that serious language of the palace of power—and thrown them up in the air with the confidence of a juggler. The result might be Instagrammable, but, like the art it heralds, it’s worth a longer look.

Click plan to enlarge

Click drawings to enlarge