When it comes to museums, architects Fuensanta Nieto and Enrique Sobejano—principals of the office Nieto Sobejano—are past masters. The husband-and-wife duo has worked on about a dozen or so since founding their Madrid-headquartered firm in 1984, showing themselves to be particularly adept at enlarging and transforming existing buildings. Crucial in helping them win last year’s competition for the future revamp of the Dallas Museum of Art, this expertise also secured them the commission for another, very similar, exercise in Germany—the renovation and enlargement of the Bavarian State Archaeological Museum in Munich. A decade after Nieto Sobejano’s Berlin office was awarded the $44 million job, in 2014, the Archäologische Staatssammlung München (ASM), as it is known in German, reopened to visitors this April.

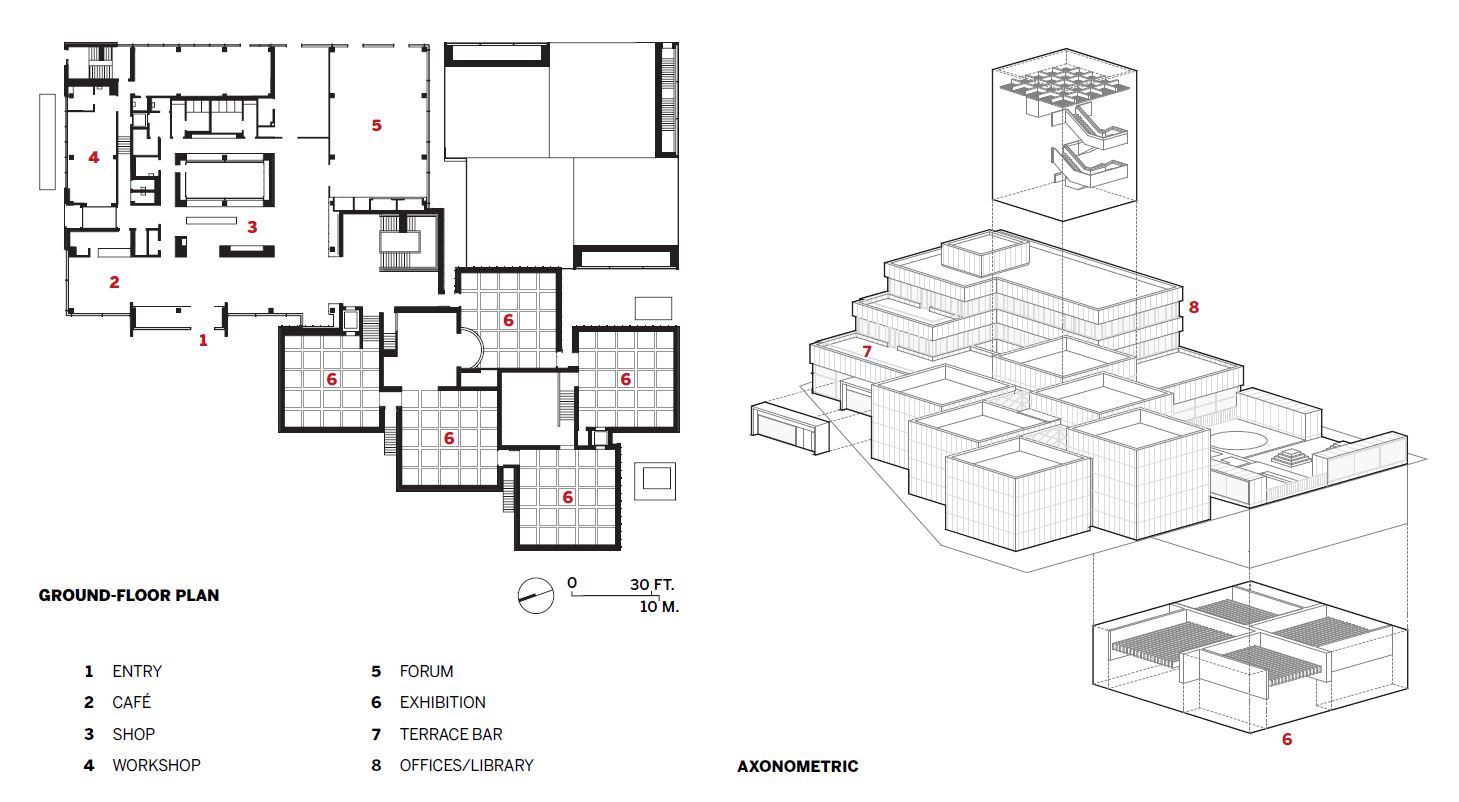

Established in 1885, the ASM has occupied its own purpose-built home since 1976. Located to the rear of the grand late 19th-century Bavarian National Museum, facing the greenery of the city park known as the Englischer Garten, the building was designed by the local firm of von Werz, Ottow, Bachmann, Marx, which, under the impetus of its founder, Helmut von Werz (1912–90), made a major contribution to the reconstruction of Munich after World War II. Oriented toward the park, von Werz and company’s ASM comprised two distinct parts: a block containing staff offices, archives, and the main public entrance; and a series of six staggered cubes, linked by two glass-roofed courtyards, which housed the exhibition galleries. Stepping down in height with respect to the Englischer Garten, the complex was clad in russet weathering steel, an early use of a material that has since become common for cultural buildings.

1

Six cube-like volumes, visible at street level (1), house galleries and a connecting stair (2). Photos © Roland Halbe, click to enlarge.

2

Four decades after the ASM’s inauguration, that steel, which had badly corroded, was among the many reasons the building required a major overhaul. All its systems needed updating, and the museum’s director also wanted extra space for temporary exhibitions. Invited, alongside three other firms, to make a proposal, Nieto Sobejano was the only office to suggest going underground to build the extension—as they had successfully done in 2006–11 at the Joanneumsviertel in Graz, Austria—in an approach that, even though the ASM was not landmarked, made respect for the original building its cornerstone. “For many years, the Germans considered what they call Nachkriegsmoderne—postwar Modernism—rather utilitarian and uninteresting,” says Sobejano. “We feel that architecture from this period is important, and are happy to see they’re finally taking it seriously,” continues Nieto.

A vast new subterranean gallery offers flexible, column-free exhibition space. Photo © Roland Halbe

As any architect who has attempted the exercise knows, respecting an existing building while trying to update it to modern code can prove extremely challenging. “People often ask us, ‘Apart from the extension, what did you actually do?’” says Nieto, “but there wasn’t a square foot of the ASM we didn’t touch.” To meet environmental targets, new insulation was needed, but, despite being among the densest (and therefore most expensive) on the market, it still caused the building to grow slightly taller and fatter. Consequently, the replacement steel cladding required larger panels, which are themselves thicker, for greater resistance (3 millimeters, in comparison to only 1.5 millimeters before). Inside, Nieto Sobejano faced similar difficulties when trying to preserve the spirit of the black-gridded gallery ceilings. This is not to say that their respect for the original ASM is in any way slavish, since the refurbishment includes numerous changes, among them an entirely reconfigured, more welcoming entrance; a new café that includes outdoor seating on a previously inaccessible roof; the greening of all the building’s other roofs; new terrazzo floors throughout; and the addition of a new main stair inside one of the six gallery cubes. Clad in warm, dark wood that echoes the external weathering steel, the stair provides access to every floor of the public circuit, including the biggest new intervention of all, the subterranean temporary-exhibition gallery.

Located beneath the playground of the next-door daycare center (a space now transformed, at the architects’ suggestion, into an “archaeological garden” for children), the 88-foot-square, 16-foot-high volume is entirely column-free, thanks to what Sobejano describes as a “reciprocal structure” in which four offset concrete roof panels, reinforced with vast quantities of steel, work together to balance out the structural forces. “The ASM’s galleries were built according to a system of squares, a very German obsession,” he explains, “and each gallery is divided into a grid. Our idea was to reuse that grid theme in our extension, but to displace it a little.” Another German mania, he continues, is detail—“our mania too, but we can’t always achieve the results we want.” In Munich, for the anthracite-colored concrete of the extension ceiling (a nod to the black grids of the original building), the contractors were just as obsessive as the architects, testing countless combinations of sand and aggregate to get exactly the desired hue. With wall cladding in dark metal, this somber underworld space avoids Stygian gloom thanks to four light monitors (a recurring Nieto Sobejano motif) that admit indirect daylight to its perimeter.

How the extension will perform for temporary exhibitions remains to be seen—the ASM reopened without one—but the idea is that it can be divided up into two, three, or four spaces, following the cues given by its ceiling grid. As for the upstairs galleries, Stuttgart-based specialist Atelier Brückner has fitted them out with displays that evoke the idea of an archaeological dig, with some exhibits shown in sunken rectangles in the floor. Known for its particularly rich Roman and Celtic collections, today’s ASM remains also a monument to a bygone era of postwar hope and reconstruction.

The sunken displays in the gallery floor echo the original grid structure of the ceiling. Photo © Roland Halbe

Click drawings to enlarge

Credits

Architect:

Nieto Sobejano Arquitectos — Fuensanta Nieto, Enrique Sobejano, principals; Anna Lunge, project architect; John Bohlmeyer, Jorge Américo Dominguez, Oliver Hasselbach, Jean-Benoit Houyet, Lorna Hughes, Philipp Jacob, Philip Kempfer, Per Köngeter, Aleksandra Kudriashowa, Morgan Moreau, Tobias Schmalfuß, Anastasia Svirski, Mariana Varela, design team

Engineers:

Sailer, Stepan & Partner (structural); Canzler Ingenieure, Teuber + Viel, Duschl Ingenieure (mechanical)

Consultants:

MGK (landscape); Priedemann Fassadenberatung (facade); Müller-BBM (fire safety); Ingenieure Süd (construction physics, acoustics); Oswin Nikolaus (lighting); Drees & Sommer (project management)

Client:

Bavarian Building Authorities Munich

Size:

7,500 square feet (new)

Cost:

$43.9 million

Completion Date:

July 2023

Sources

Cladding:

AMS (weathering steel)

Flooring:

Hubert Pupeter (terrazzo)

Doors:

RIES Akustik-Innenausbau

Windows:

Radeburger Fensterbau (aluminum)

Furniture:

Schreinerei Vogl

Interior Metalwork:

Metallverarbeitung, André Taubert (steel)

Exhibition Hall:

Wayss & Freytag Ingenieurbau, Steinmetzbetrieb Miedl (bush-hammered concrete)

-Hamon-Forecourt-View--Nieto-Sobejano-Arquitectos.jpg?height=200&t=1691218537&width=200)