The mesmerizing rhythm of waves, the unbroken line of the horizon, and the scent of salt in the air are just a few of the qualities that irresistibly draw people to where the land meets the sea. These environments, however, with their often perilous terrain, changeable weather, and strong currents, can be inhospitable to wading, let alone swimming. But sea pools—man-made basins at the surf’s edge, sometimes carved from rock faces, sometimes cast in concrete—offer protection from such threats, while allowing access to the water. “These liminal places bridge the space between a chlorinated pool and the open ocean, providing a dose of the wild in an enclave of safety,” explains London-based architect Chris Romer-Lee in the introduction to his recently published Sea Pools: 66 Saltwater Sanctuaries from Around the World.

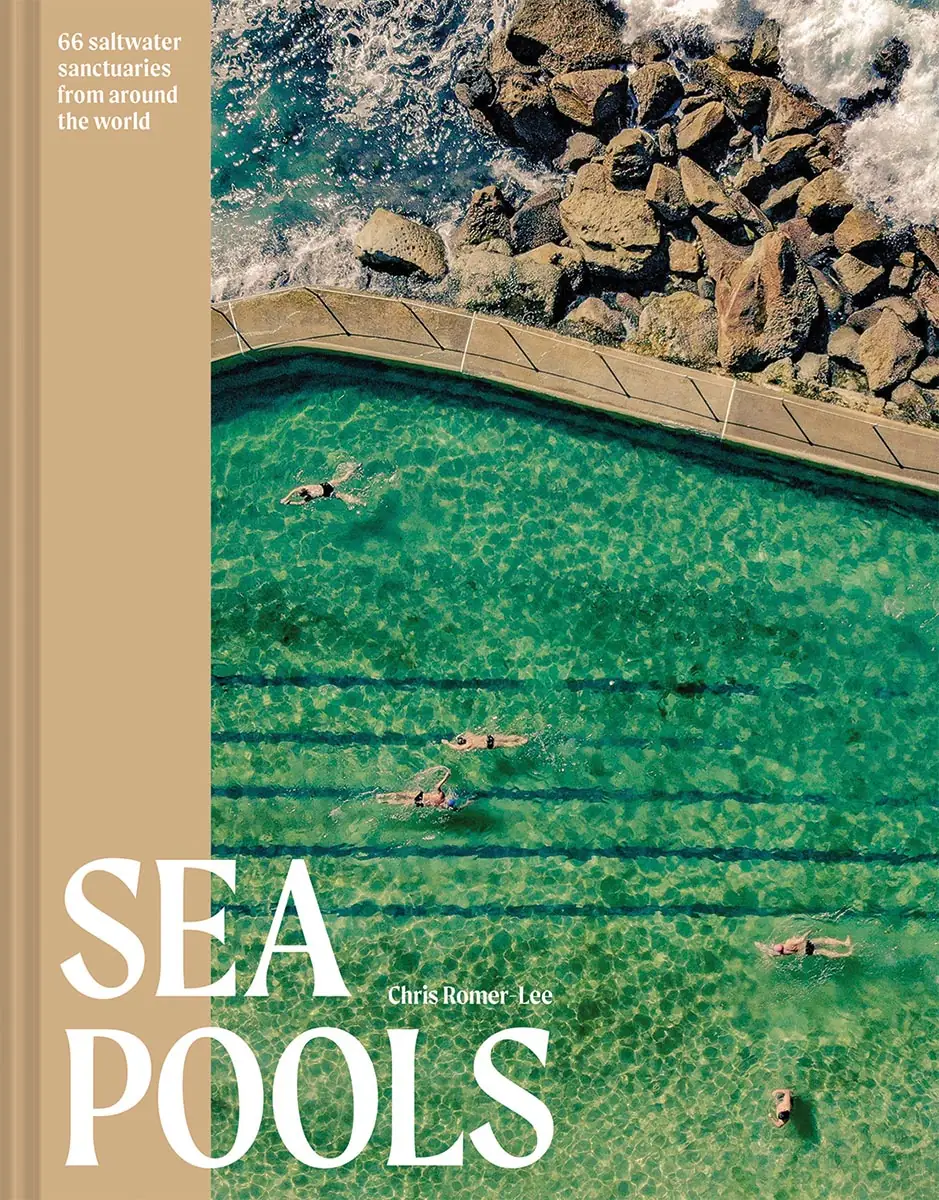

Sea Pools: 66 Saltwater Sanctuaries from Around the World, by Chris Romer-Lee. Batsford, 192 pages, $32.

The book concentrates on tidal pools (those that are naturally refreshed twice daily by high tide) and documents saltwater havens in continental Europe, the United Kingdom, Africa, Australia, and beyond. It is a natural outgrowth of Romer-Lee’s practice, Studio Octopi, for which water and swimming are a particular focus. Among its projects is the restoration of historic lidos (outdoor public swimming facilities) in the UK. The firm is also the creator of a proposal for a much published but still unrealized central-London floating pool in the Thames. Notably, Romer-Lee swims in the Serpentine Lake in London’s Hyde Park every morning, year-round.

The range of Sea Pools is not only geographic. It features modest and scrappy swimming holes like Mousehole Rockpool in Cornwall, England, a small and shallow wading spot built in 1970 by a local resident with the help of family members and others with money raised from the community. It also includes those that are expansive, such as the early 1990s Harmony Park, in Cape Town, which at 11 acres is large enough to incorporate several man-made islands, some containing their own plunge pools.

In his introduction, Romer-Lee touches on a number of themes: he recounts the rise of sea bathing from the middle of the 18th century in England due to a new faith in ocean water’s curative properties; the transformation of naturally formed sea pools in Australia, first used as fishing grounds, into recreation areas for colonists, as the European settlers pushed indigenous peoples inland; in South Africa, the fraught issue of beach access during apartheid; and the ravages of water pollution and global warming on the seaside. He also points to the potential for sea pools to serve as social infrastructure, or “liquid piazzas.” They are not only places where people meet to soak up the sun, swim, and socialize, but causes around which they rally to protect and maintain. One example is The Trinkie, a nearly 200-foot-long naturally formed pool embedded in a rock plateau in Wick, in northern Scotland. With concrete walls added in the 1930s to help contain the water, Trinkie is cleaned and repainted each year by a group of dedicated volunteers.

The Trinkie, in the Scottish Highlands, is maintained by a dedicated group of volunteers. Photo © Iain Masterton

Many of these same ideas are further explored in several essays, including one by Nicole Larkin, a Sydney-based architect and coastal-planning expert, which discusses the potential for a next generation of sea pools to allow people to occupy the water’s edge while restoring natural ecological systems, and another by London-based writer Freya Bromley that recounts her attempt to swim in every tidal pool in Britain over the course of a year in the wake of the death of her brother.

The profiles of individual pools are, naturally, the heart of the book. The oldest pool is Lady Basset’s Baths, a series of bathtub-like hollows cut into the rock at Portreath, England, in the late 18th century, while the youngest was built in 2015 as part of a new residential neighborhood in Tananger, Norway. Sea Pools covers the circumstances of the 66 profiled swimming spots’ development, their history, and their current status. Some are now closed but are to be refurbished, including Saltcoats Bathing Pond, in North Ayrshire, Scotland, which Studio Octopi has been commissioned to restore.

The book’s seductive photographs feature foamy surf, craggy cliffs, and enticing blue water. The only drawback is that there are not more of these images (most pools are illustrated with just a single shot). Additional photos would help the reader better understand the relationship to the broader landscape, provide a sense of scale, and give some idea of the conditions in different weather or various seasons. But Sea Pools provides invaluable insight into the historical, social, and environmental importance of these collaborations of the land, the sea, and humans. The book goes well beyond its stated purpose of serving as “a springboard to whet the appetite of those interested in exploring these natural wonders further.” This reviewer has already added several of the destinations to her swimming bucket list.