On Friday, June 28, the Stonewall National Monument Visitor Center in Manhattan’s Greenwich Village opened to the public at a ceremony attended by President Joe Biden, New York Governer Kathy Hochul, and Elton John, among other high-profile public figures. The day marked the 55th anniversary of the Stonewall uprising, a series of violent clashes between the police and LGBTQ+ protestors, centered around an underground bar on Christopher Street, that sparked the modern gay rights movement. In 2016, a year after legalizing gay marriage, President Barack Obama designated the building, and the surrounding 7.7-acre area, as a United States national monument under the National Park Service—the first in the country dedicated to LGBTQ+ rights and history.

EDG Architecture and Engineering restored the facade of 51 and 53 Christopher Street in early 2023. Photo © Stephen Kent Johnson

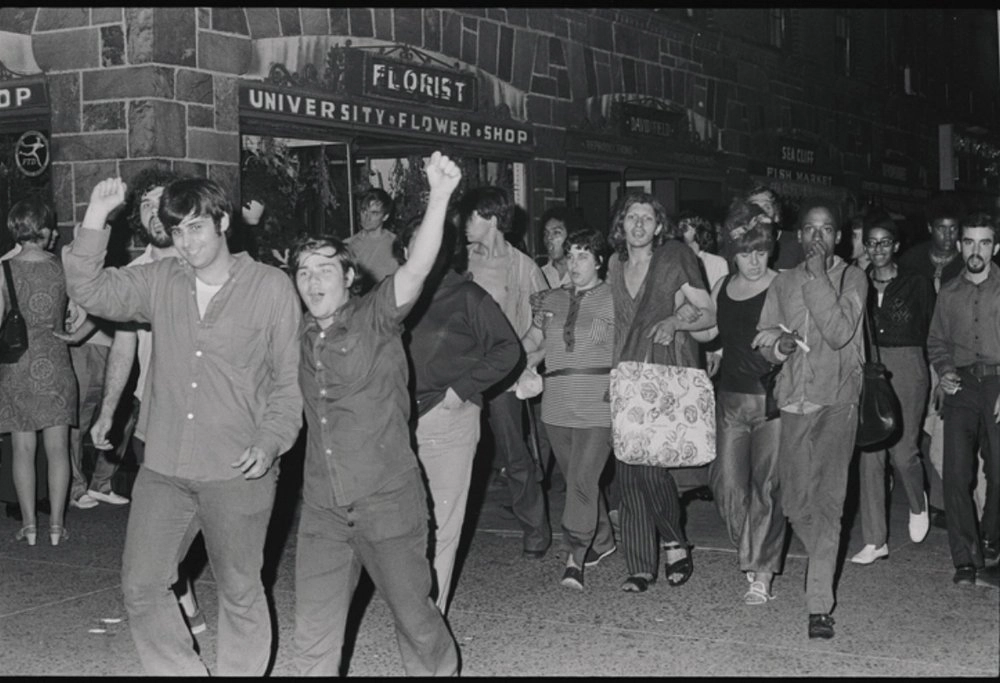

Protestors on Christopher Street in 1969. Photo courtesy Mark Stonewall

Opened in 1967, the original Stonewall Inn occupied two adjoining storefronts at 51 and 53 Christopher Street, which were originally built as horse stables in the 1840s. Connected by a brick doorway cut into the shared wall, the shabby and makeshift space was notable as the only gay bar in New York City that allowed open dancing and became a vibrant center for queer life. “There’s a certain hastiness about the look of the place,” reads a description of the original Inn from the 1968 Homosexual Handbook. “It seems to have only recently been converted from a garage into a cabaret; in about eight hours and at a cost of under fifty dollars.” The original establishment was shuttered soon after the uprising, but the space at 53 Christopher Street was revived as a bar of the same name in the 1990s.

The adjacent storefront has had many lives in the decades since—most recently a nail salon and then a bagel shop—until six years ago, when Diana Rodriguez and Ann Marie Gothard of the non-profit LGBTQ+ advocacy group Pride Live began a campaign to open a visitor center in the space. The organization ultimately raised $3.2 million and assembled a star-studded list of collaborators, among them Madonna and Chelsea Clinton, and a rainbow brigade of corporate sponsors, including JP Morgan Chase, Amazon, and Target. The 3,700-square-foot new space, designed by local firm EDG Architecture and Engineering, is co-programmed by Pride Live and the National Park Service, and will feature long- and short-term exhibitions dedicated to LGBTQ+ history and culture, and host events and lectures in its dedicated theater. Entry for the public is free of charge.

Photo © Stephen Kent Johnson

Joining EDG on the larger project team were exhibition designer Local Projects, lighting designer Orsman Design (with lighting controls and fixtures by Lutron), audio-visual consultants HMBA, and WB Engineers + Consultants. Interior designers Nake Berkus and Jeremiah Brent also lent expertise and support.

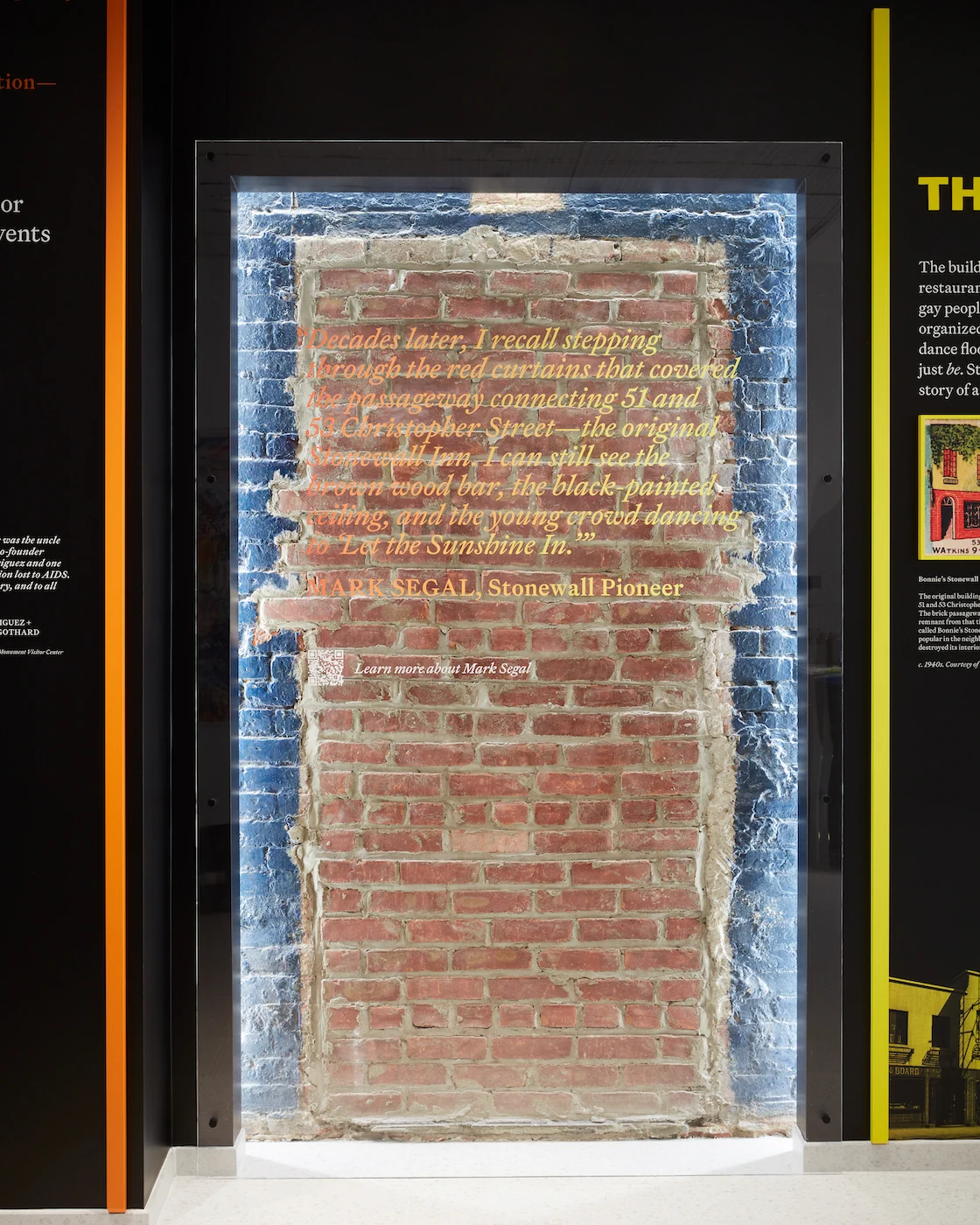

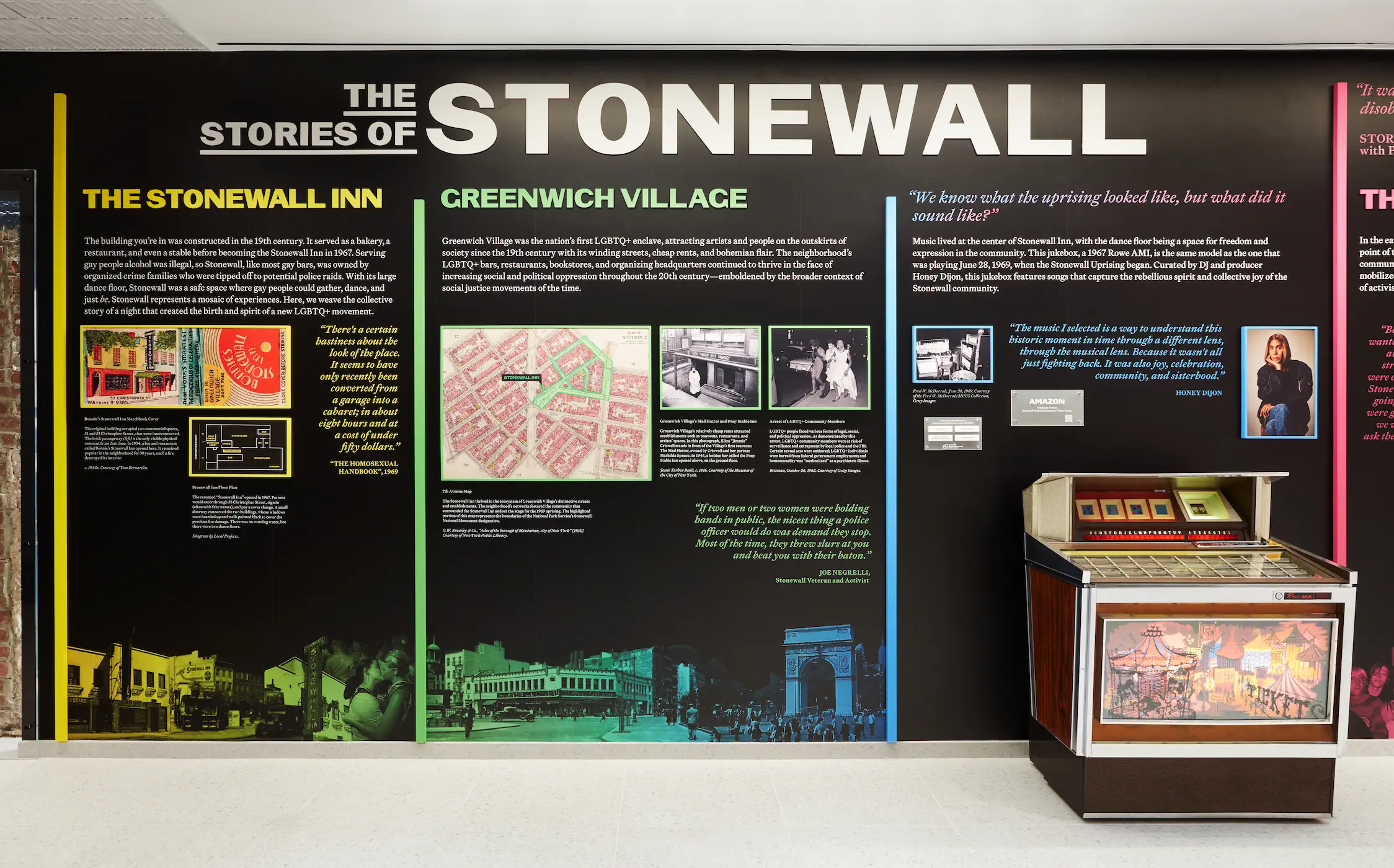

The renovation maintained the historic red-brick facade of the storefront, but added a window, a contrast to the boarded-up, blacked-out windows of the original inn, mandated by the repressive atmosphere of the time. Stepping inside, visitors are greeted by a white-box interior, which hosts a permanent long-term exhibition on one wall, designed by Local Projects, that explores the history and significance of Stonewall. This exhibition also frames, preserved behind glass, the original entryway once connecting the two spaces. “It was important for Pride Live to be able to have a space that operated very much like a gallery, with a clean, very legible interior,” says Richard Unterthiner, design director and associate principal of EDG. “We really wanted to become the backdrop and present something very minimal that would allow visual displays to really come to the fore.”

In addition to the long-term exhibition, gallery space includes a rotating installation designed by students from the Parson’s School of Design, to be produced each semester in a partnership with Pride Live that seeks to incorporate Stonewall history into the school’s curriculum. A small gallery wall near the street entrance will feature work by artists from the LGBTQ+ community.

1

2

The original entryway, bricked over after the Inn's closing, is preserved behind glass (1); the rotating exhibition designed by Parson's students. Photo © Stephen Kent Johnson

Despite the minimalism mandated by the brief, the architects found ways to incorporate nods to the past into the design, relying on first-hand accounts, material remnants, floorplans, and a singular existing photograph of the original interior. The original bar’s tin ceilings are memorialized in the pattern of the ceiling, and a steel-framed outline of the bar is cemented in the floor where it once stood. A functional replica of the jukebox shown in the aforementioned photograph (taken after the June 28 raid) is installed in front of the long-term exhibition wall, and programmed with a playlist curated by trans DJ and electronic musician Honey Dijon.

3

4

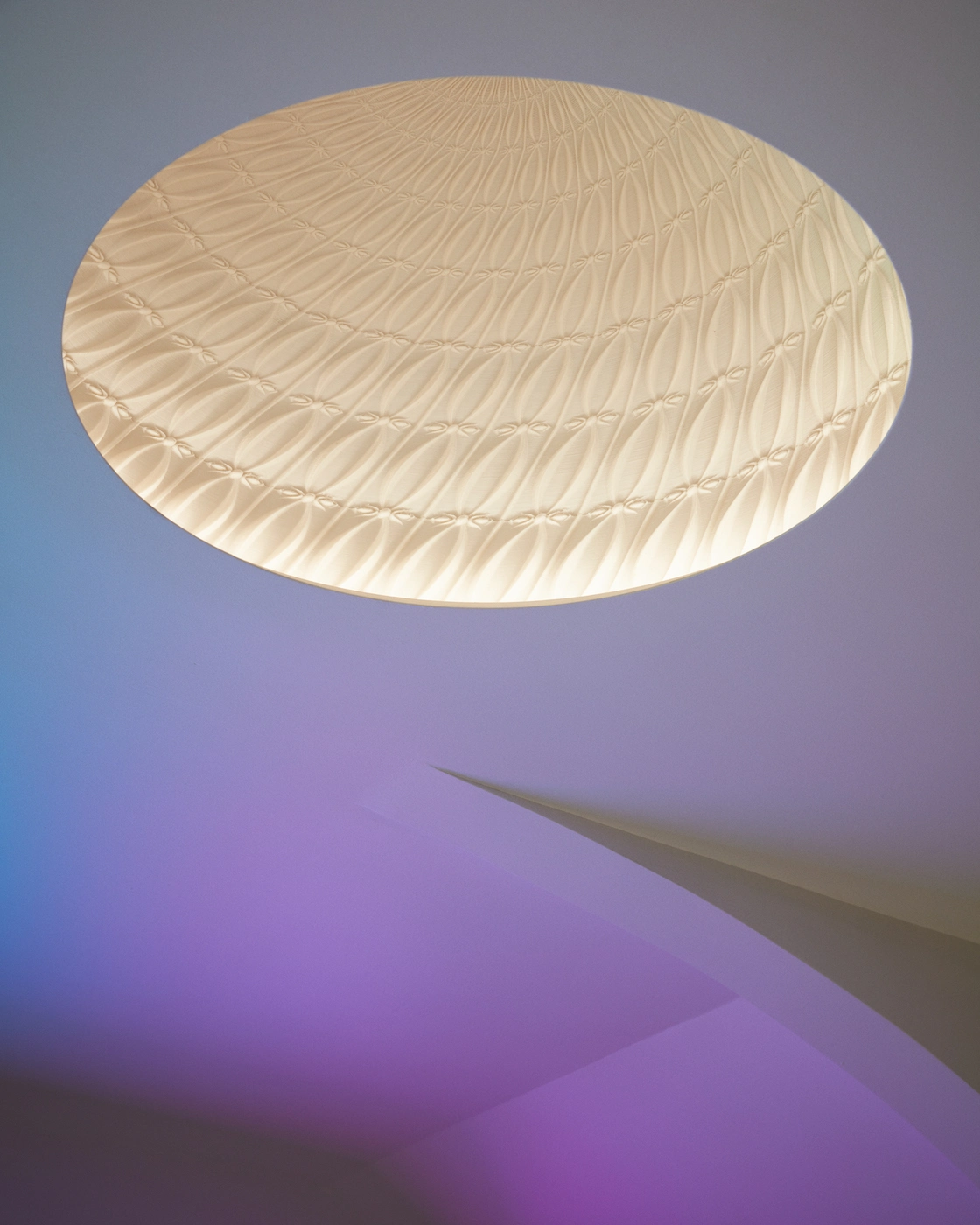

The long-term exhibition includes a functional jukebox (3); the Center's dedicated theatre space (4). Photos © Stephen Kent Johnson

Other memorial “touchstones,” to use the architects’ term, include two 3D-printed luminaires, created in collaboration with Synthesis, inset into the ceiling. The first, located above the reception desk, features the same pattern from the tin ceiling panels and the second, by the bathrooms, pays homage to a Keith Haring work in the bathroom of the nearby Gay and Lesbian Center. The locations of each are informed by the idea of spaces of exchange and socialization, says Unterthiner: “With a reinterpretation that uses new technologies, we’re speaking to the narrative of past, present, and future.”

5

6

The architects implemented two 3D-printed luminaires; one above the reception desk (5), and one by the Center's bathrooms (6). Photos © Stephen Kent Johnson

This equal emphasis on past and future that guided the design of the Visitor Center will carry its mission into the future, which is to cement the area’s historical legacy and create a physical center for the neighborhood’s (and New York’s) queer community. “We want people to feel truly welcome, acknowledged, and seen. It’s symbolic on many levels—you can come inside, be proud, and be part of the conversation,” says Unterthiner. “It’s about creating a place where people feel they have a home.”