Nestled at the convergence of three regions in northern Spain, Aguilar de Codés is a place of overlapping influences and layered histories. The Basque country, La Rioja, and Navarre meet here, leaving traces of their varied cultures on the buildings, the cuisine, and the people. The sport of pelota exemplifies the region’s multiple identities—a shared recreation played in diverse ways: with one’s bare hand, a racket, a bat, or a chistera (a wicker scoop) propelling a ball against a wall.

As in other parts of rural Spain, young people have moved from Aguilar de Codés to larger cities in search of employment and excitement. Today, it has fewer than 100 year-round residents, though the number increases on weekends and holidays, when family members return to visit and tourists come to relax. Luring people to town was one of the reasons the local city council decided to build a pelota frontón, or walled court, using the site of an old stone mansion that had fallen into ruin. After a limited competition, the city hired Verne Arquitectura with Alejandro Maortua Gaminde to design the project, challenging the architects to respect local building traditions and the physical context.

“Here, there’s a strong cultural relationship with the sport of pelota,” says Víctor Larripa Artieda, one of Verne’s three partners, along with Javier Martínez Labeaga and Daniel Ruiz de Gordejuela Tellechea. “Basically, every town has a frontón.” Except Aguilar de Codés—until now.

Many of the frontónes in the surrounding region are large boxes seemingly dropped like alien structures into the existing—often historic—fabric. “We didn’t want a UFO,” says Larripa. For this project, the firm, which has small offices in Pamplona and Bilbao, collaborated with Maortua, who had worked for Verne before setting up his own practice but remains close to his former colleagues. Fronting the town’s main street, the 8,600-square-foot project had to respond to both the aging masonry structures nearby and views of the rolling landscape in the distance. To reduce the apparent bulk of the new building, the architects pushed its main volume 6 feet below street level, nearly matching the roofline of its neighbors. The designers also created a set of concrete steps running along the south edge of the frontón that serve as seating for spectators and negotiate the change in topography.

Horizontal courses of sandstone clad the exterior (top of page), while precast concrete lines interior walls (above). Photo © Pablo García Esparza, click to enlarge.

Although constructed of precast-concrete panels, and clearly modern in appearance, the project honors the noble villa that it replaces in a number of ways. Its footprint roughly follows that of the old house and an adjacent shed, while its hipped roof echoes the form of its predecessor’s. Though its concrete structure is exposed on the inside, the building is clad on the outside with sandstone from Catalonia that has been chiseled with slender vertical grooves to produce a texture reminiscent of the town’s historic buildings. False openings on three sides recall the size and placement of windows on the former mansion, though today they are backed by precast panels. The only opening that isn’t blocked by concrete, located on one of the short sides and acknowledging the placement of an old doorway, now offers passersby a view into the frontón. In another nod to the past, the architects returned the villa’s coat-of-arms to its place of honor, just above this aperture.

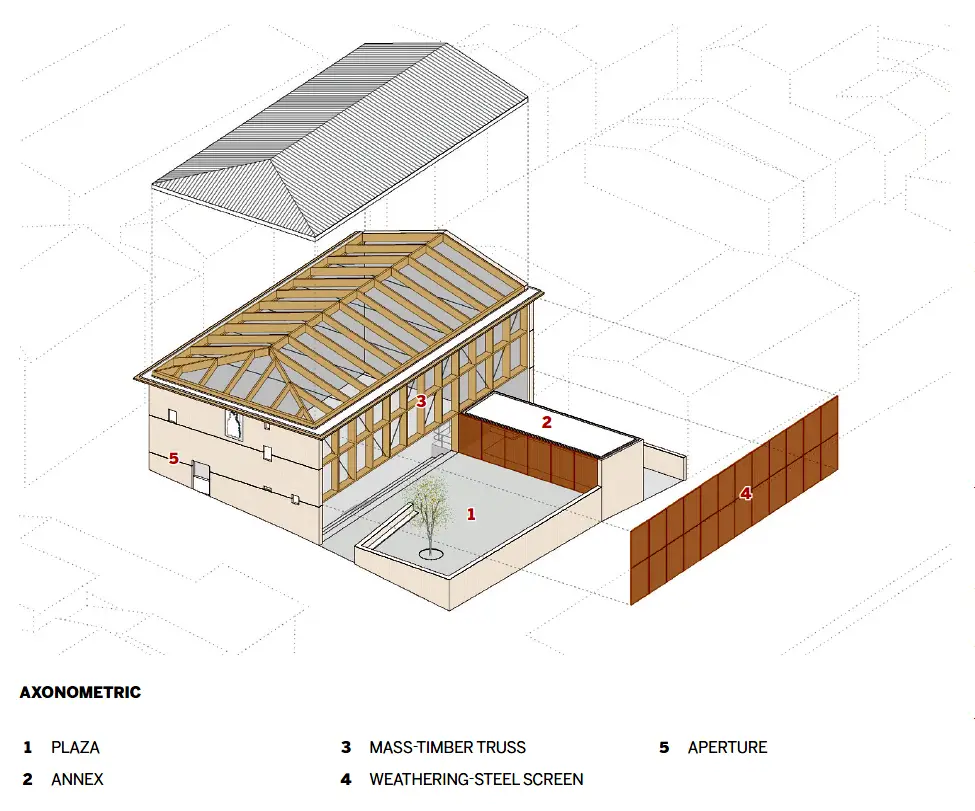

A low annex with changing rooms, restrooms, and space for community functions extends perpendicularly from the frontón on the south and helps define an outdoor plaza that serves as a social gathering place and playground and can host civic events such as festivals. A vertically slatted screen of weathering steel runs along the plaza-facing elevations, creating an intriguing dialogue of materials among old and new structures in town. A long truss of glue-laminated wood and angled steel cables on the frontón’s south facade elegantly holds up part of this scrim, as well as the wood-frame roof, allowing light and air to flow between indoors and out.

A mass-timber truss supports the frontón’s roof and weathering-steel screen. Photo © Pablo García Esparza

“We like humble, honest architecture and buildings one can easily understand,” says Larripa about his firm’s design approach. “For this project, integrating the building with its context was particularly important, both to us and the client.”

Instead of merely replacing a crumbling villa with something modern, Larripa and his collaborators have added a new chapter to the rich history of Aguilar de Codés, designing a building that conjures the ghost of its predecessor while expressing a contemporary spirit and function. The sport of pelota reaches back to the 13th century, but it continues to resonate with people today, and frontónes still act as social hubs tying residents to their towns.

Click drawing to enlarge

Credits

Architects:

Verne Arquitectura with Alejandro Maortua — Víctor Larripa, Daniel Ruiz de Gordejuela, Javier Martínez, principals; Leire Artieda, Itsaso Otermin, Guillermo Martínez, Carmen García, design team

Engineers:

ATEC Aparejadores (construction); Elice Ingeniería (electrical); Josep Agustí (structural)

General Contractor:

ERKI Construcción

Client:

Aguilar de Codés City Council

Size:

8,600 square feet

Cost:

$763,000 (construction)

Completion Date:

April 2024

Sources

Structure:

Madergia (timber); Viguetas Navarra (precast concrete)

Masonry:

Floresta Sandstone

Metal:

Cor-Ten steel (screen, doors)

Finish:

Celenit (acoustical ceiling)

Lighting:

Nexia, Phillips, Dopo Lighting

Plumbing:

Roca (faucets, sinks, toilets)

.jpg?height=200&t=1711436853&width=200)