Exhibitions at the National Building Museum Explore D.C. Brutalism and Frank Lloyd Wright in Pennsylvania

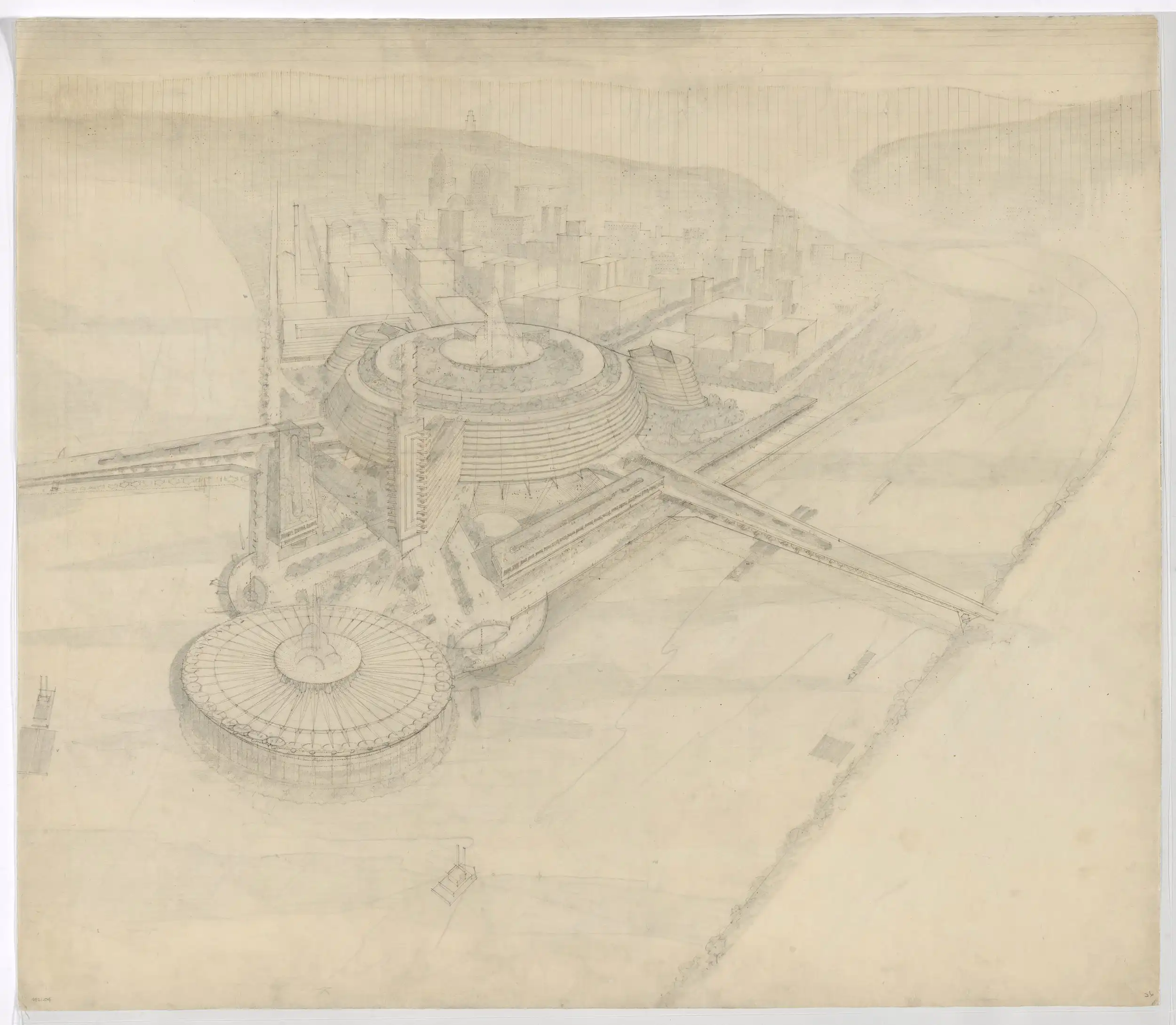

Lauinger Library at Georgetown University (left); Frank Lloyd Wright, sketch of Point View Residences for the Edgar J. Kaufmann Charitable Trust (Scheme II), 1952 (right). Images: © Ty Cole (left); The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University), 5310.001

Two new exhibitions at the National Building Museum (NBM) in Washington, D.C., examine particular strains of Modernism in different places—and then wonder what could be or what might have been. Capital Brutalism looks at the architectural style that found fertile soil in D.C, in the 1960s and 1970s and later became the type of design the public loved to hate. Focusing on seven polarizing examples of Brutalism, it presents brief histories of these projects and then offers an alternative future for six of them. The other exhibition, Frank Lloyd Wright’s Southwestern Pennsylvania, shows a range of works designed by the architect from the 1930s through the 1950s in Pittsburgh and the area around Fallingwater, the landmark house he created for department store magnate Edgar J. Kaufmann. For five of those projects—ones that weren’t built—Skyline Ink Animators + Illustrators has produced animated films that depict what they would have been had they been realized.

-Ty-Cole.webp)

J. Edgar Hoover Building (1975). Photo © Ty Cole

Federal buildings are often targets of criticism, but federal buildings designed in the Brutalist style seem to generate a particularly intense strain of invective. The J. Edgar Hoover Building (1975), which serves as headquarters of the FBI, for example, has been voted one of the ugliest buildings in the world. Located roughly a mile away, the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s home base at the Robert C. Weaver Federal Building (1968), was called in 2009 “among the most reviled in all of Washington—and with good reason,” by none other than the secretary of HUD at the time, Shaun Donovan. A previous HUD secretary, Jack Kemp, described the building as “10 floors of basement.” Some examples of D.C. Brutalism have been torn down, including the Third Church of Christ, Scientist, designed by Araldo Cossutta of I.M. Pei & Partners in 1970, and razed in 2014. Others have bull’s eyes on their broad concrete facades and may yet confront dates with the wrecking ball.

Washington Metro (1976–). Photo © Ty Cole

As we wrestle with issues of sustainability, though, we’re beginning to realize that tearing down buildings is a wasteful way of updating our cities. And so, strategies to adaptively reuse existing structures are garnering growing support among the public, building professionals, and academics. Capital Brutalism, co-organized by the NBM and the Southern Utah Museum of Art, and co-curated by Angela Person of the University of Oklahoma and architectural photographer Ty Cole, presents plans for re-inventing six of the seven projects in the exhibition. The seventh one—the Euram Building by Hartman-Cox Architects—is an outlier here in many ways, being a privately owned corporate headquarters rather than a government or university building and trying to fit into its Dupont Circle context rather than stand out from it.

Hirshhorn Museum (1974). Photo © Ty Cole

The schemes to transform six “imposing monsters” in the nation’s capital range in their degree of subversion from sneaky but powerful to bold but silly. A personal favorite is Diller Scofidio + Renfro’s inflatable bubble that would emerge from the concrete donut that is Gordon Bunshaft’s Hirshhorn Museum (1974). Commissioned in 2009 by then-museum director Richard Koshalek, it would have served as temporary event space for a couple of months each year—requiring just one week to erect and half an hour to inflate. The light blue bubble would have popped up above and leaked out from under the existing structure, alerting visitors on the National Mall that something was happening at the Hirshhorn. More important, it would have humanized the museum’s austere image, injecting a touch of levity (literally) to the museum’s all-too-serious demeanor. After crunching the numbers, the powers-that-be at the Smithsonian Institution said it would cost too much and cancelled the project. In 2022, the museum hired SOM and Selldorf Architects to update the Hirshhorn’s interiors and plaza as part of the largest revitalization project in the museum’s history.

With many government employees still working remotely, some large federal office buildings are under-utilized, relics of a time before Covid and Zoom. HUD’s much-maligned Weaver Building, designed by Marcel Breuer, embraces 700,000 square feet within a pair of enormous curving wings. As shown in the exhibition, Brooks + Scarpa proposes a radical transformation—converting about 45 percent of the space to affordable housing, updating offices to a new work culture, adding retail and public uses to the ground level, and creating a set of cascading terraces, planted rooftops, and glazed atria in the area between the two wings. The Los Angeles–based firm wisely retains the gridded concrete-and-glass facades of Breuer’s sweeping structure, while adding all the new stuff to what had been a dark, central core.

Robert C. Weaver Federal Building (1968). Photo © Ty Cole

Studio Gang takes a more subtle, but equally powerful, approach to re-envisioning the Department of Energy’s 760-foot-long James V. Forrestal Building, designed by Curtis and Davis in 1969. By removing a piece of the old structure, the firm would break down its massive scale and open a view to the Smithsonian Castle. It would add mass-timber pavilions on top of the roof, reduce floor slabs to let in more daylight, reclad newly exposed edges in wood, and install operable windows.

Other projects in the exhibition include Gensler’s “hacking” of the FBI’s Hoover Building to turn it into a mixed-use complex with a rooftop soccer field, big-box retail, and hotel; D.C-based 2023 Design Vanguard BLDUS’s transformation of HEW’s Hubert H. Humphrey Building into a “Temple of Play;” and the University of Nevada, Las Vegas School of Architecture’s re-thinking of John Carl Warnecke’s Lauinger Library at Georgetown University.

While the exhibition doesn’t explore in any depth the ideas behind the original Brutalist architecture, it includes contemporary reviews of the buildings by critics such as Ada Louise Huxtable, Hilton Kramer, and Benjamin Forgey, and some articles from publications like Architectural Record. Recent photographs by Ty Cole show what the buildings look like today.

1

2

Animation stills of project for Civic Center at Point Park for the Allegheny Conference, 1947, digital illustration, 2021 (1); project for Point View Residences for the Edgar J. Kaufmann Charitable Trust, digital illustration, 2023 (2); Designs by Skyline Ink Animators + Illustrators, prepared with material kindly made available by the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Courtesy of Western Pennsylvania Conservancy. All rights reserved.

Frank Lloyd Wright, bird’s-eye view sketch from Mount Washington, project, Civic Center at Point Park for the Allegheny Conference, 1947. Courtesy the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University), 4821.004

-(1).webp)

Installation view of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Southwestern Pennsylvania at the National Building Museum. Photo courtesy NBM

Capital Brutalism is on view through February 17, 2025, and Frank Lloyd Wright’s Southwestern Pennsylvania is on view through March 17, 2025. More information can be found here.