Civic Architecture 2024

A Church and Community Center by Elding Oscarson Prizes Simplicity Over Spectacle

Gothenburg, Sweden

Architects & Firms

Perhaps unsurprisingly, a long history of dissent and convention-breaking surrounds Sweden’s “free churches,” known as frikyrkor, which emerged in the 19th and 20th centuries when there was a state religion. Amid the spire-dotted skyline of Gothenburg, one such congregation—the Pentecostal Smyrnakyrkan—slowly but surely outgrew its steepleless downtown refuge south of King’s Park. With the parish’s centennial on the horizon and the city looking to spur development in its former docklands, the two sponsored an architectural competition for a new, bigger spiritual home.

Four firms made the shortlist: the Stockholm-based studio Elding Oscarson, the firm of Danish starchitect Bjarke Ingels, Swedish powerhouse Wingårdhs, and a team comprising Gothenburg-based Thorbjörnsson+Edgren and the Paris office of Kengo Kuma, whose scheme of colliding A-frames—some split at their ridge to introduce daylight—was as daring as it was impractical, given financial constraints. “The budget made the project very challenging,” says architect Johan Oscarson. “We really wanted to address this with our proposal—to find a way to make a robust but basic concept.” In the end, simplicity won over celebrity or divine spectacle.

But the cuboid Frihamnskyrkan—or Freeport Church—aspires to be more than merely a religious institution or home of the multicultural congregation of 3,400. Situated in the newly developing neighborhood of Frihamnen, along the northern banks of the Göta River, the building doubles as a community center. As was important to the parish, the new location made it more accessible to residents who live in the historically lower-income and more industrial parts of the city.

A tripartite composition defines the church’s simple but monumental volume. Transparent glazing wraps the base, offering passersby a glimpse of the goings-on inside. Above, planks of acetalized wood sheathe the midsection, broken only by a single cruciform aperture—the sole explicit indication of the building’s religious function. The uppermost floors are enclosed within a curtain wall of panelized aluminum that emphasizes vertically banded fenestration of varying widths. Affixed in front of this system is a scrim of diagonally oriented aluminum bars. “We experimented with different geometries, like circles, but the expression always seemed more like a synagogue or a mosque, and didn’t communicate the idea of Christianity,” co-principal Jonas Elding explains of early sketches. Instead, this crown aims to represent an abstracted sheaf of wheat, an allusion to the New Testament parable about reaping what one sows, as well as to Smyrnakyrkan’s emblem. The appliqué, as superficial as it may be, drew the clients to the scheme—and it indeed creates an ever-changing moiré pattern with corners that terminate with crosshatched flourishes.

Inside, rooms feel abuzz. “We call the ground floor the church square,” says Elding to the sound of clattering dishes and a soft hum in the background. Parishioners and the public mingle in this indoor plaza at the café, or chat following shows in a small multiuse hall, where an organist was playing a matinée. “A lot of people just come here to talk, and that’s very important for us,” adds Kjell Bramwall, a long-standing congregant who served as the client liaison during design and construction. At the far end of the first level, an industrial kitchen and commissary allow volunteers to continue their practice, with more room, of preparing meals for those in need.

Rather than squeeze the main church hall into a space amid all these community-oriented programs, the architects allocated a single area on the second floor. Given this elevated position, parishioners enter it from below after ascending a curved staircase and passing through a modest anteroom—a sequence that heightens the transition into the expansive, 32-foot-tall room with seating for 1,100.

As with the exterior, few elements directly suggest a religious purpose aside from the cross hanging on one wall. “They didn’t need symmetry, a central aisle, or even an east-facing altar. The congregation is very relaxed, and that’s a part of its identity as separate from the state church,” Elding explains. The architects instead aimed to evoke early Christianity, when followers would gather in the landscape—another design idea that swayed the jury in their favor. Accordingly, terraced groupings of raked seats form a hill-scape of earthy beiges and taupes trained on a stage-like dais with a shallow thrust. Tall, thin windows—not dissimilar to those lining a Gothic nave—flood the hall with an otherworldly glow from all sides, as if the light were filtered through a forest of trees. The muted palette and unadorned interiors may be bare-bones, but the ensemble is fittingly Protestant—somehow both sacred and secular.

1

Terraced groupings of seats create an indoor hill-scape (1 & 2), a design illustrated by the architects early on (3). Photos © Johan Dehlin (1 & 2), click to enlarge.

2

3

The church hall’s inherent flexibility accommodates far more than sermons and baptisms. Curved walls with projecting battens enhance acoustics, as do perforated panels on the outer walls and the ceiling, above which is a concealed space for technical equipment used in performances. (At the time of my visit, a Christian rock band was setting up for a concert.) Tucked beneath the seating embankments, highest in the room’s four corners, are various back-of-house functions, including space for AV production to support the simultaneous translation of Swedish into English, Spanish, and Portuguese, as well as a somber prayer room.

Holding up the 130-foot-square column-free expanse (and three additional floors above it) are a series of 25-foot-tall steel Howe trusses, partially exposed in the uppermost floors. Although the architects had initially proposed a mass-timber structural system, at the time of the competition, such a frame would have cost about 20 percent more, according to Oscarson.

A spiral staircase in a skylit atrium connects a number of supplemental spaces in the church. Photo © Johan Dehlin

Organized into a nine-square grid, floors four through six accommodate classrooms for a junior college (not operated by the church), offices for parish administrators as well as leasable ones, a day-care center, a sixth-floor church hall, and a shared kitchen in which families can cook and enjoy meals together. A west-facing roof terrace offers views of the Port of Gothenburg, the largest shipping port of the Nordic countries. But most striking is the three-story-tall skylit atrium at the center, which visually and physically connects these supplemental spaces with a helical staircase.

Not all in the surrounding neighborhood has gone according to plan. An economic slowdown in Sweden has put many of the nearby projects in Frihamnen, including the promise of a new tram line and more housing, on slower timetables. “Right now, we are focusing on the infrastructure needed to start the neighborhood,” says city architect Björn Siesjö, who also served on the jury that selected Elding Oscarson. “This is good in a way because we’ve already moved the bus lines, built playgrounds, and we’re finishing the park. That’s really the way to do it—have the amenities and infrastructure in place, then do the buildings and residential.”

Frihamnskyrkan cost an astoundingly low $240 per square foot (the parish sold its previous church in 2019 for $21 million to help fund the new one). But in a country where it can be prohibitively expensive to build, that low price tag is evident, at times to the architecture’s detriment. The acetalized wood cladding, though a durable choice, cheapens a facade that had originally been envisioned by the architects in Douglas fir. Scrapping mass timber for steel and concrete would seem a sin today. The church had to secure funding by itself, so resources were limited—an obvious constraint for the architects, who made sure that the main hall never succumbed to the same temptation of value engineering that plagued other areas.

4

5

The hill-scape in the main hall is rendered visible on the facade via the scalloped form of the wood cladding (4 & 5). Photo © Johan Dehlin (4)

“We’ve realized a string of buildings, including this church, that feature a single space that describes the entire footprint, where one can understand the building in full,” says Elding, whose firm recently won Sweden’s most prestigious architecture honor, the Kasper Salin Prize, for its mass-timber extension to the National Museum of Science and Technology in Stockholm. Both projects, Elding explains, were developed in tandem, as complements—one a celebration of the observable, the other of the ineffable. In the former, a shingled roof warps around a wood geodesic dome like a gravitational field around a celestial body, pulling visitors into its orbit. But in Gothenburg, the heavenly clarion call to come together emanates from something left unseen.

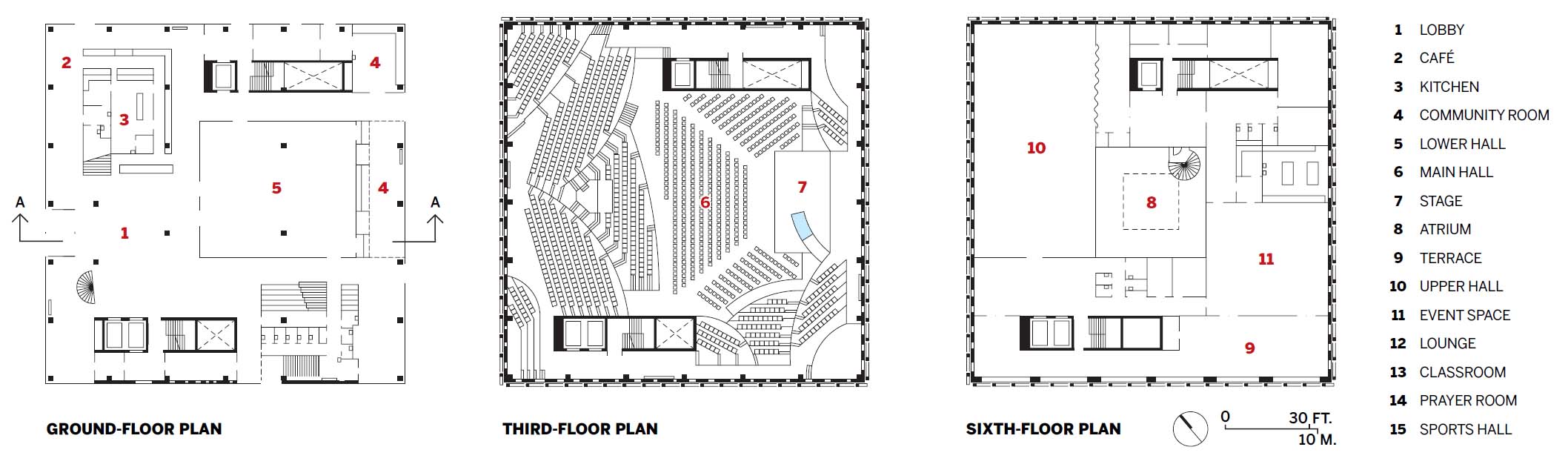

Click plans to enlarge

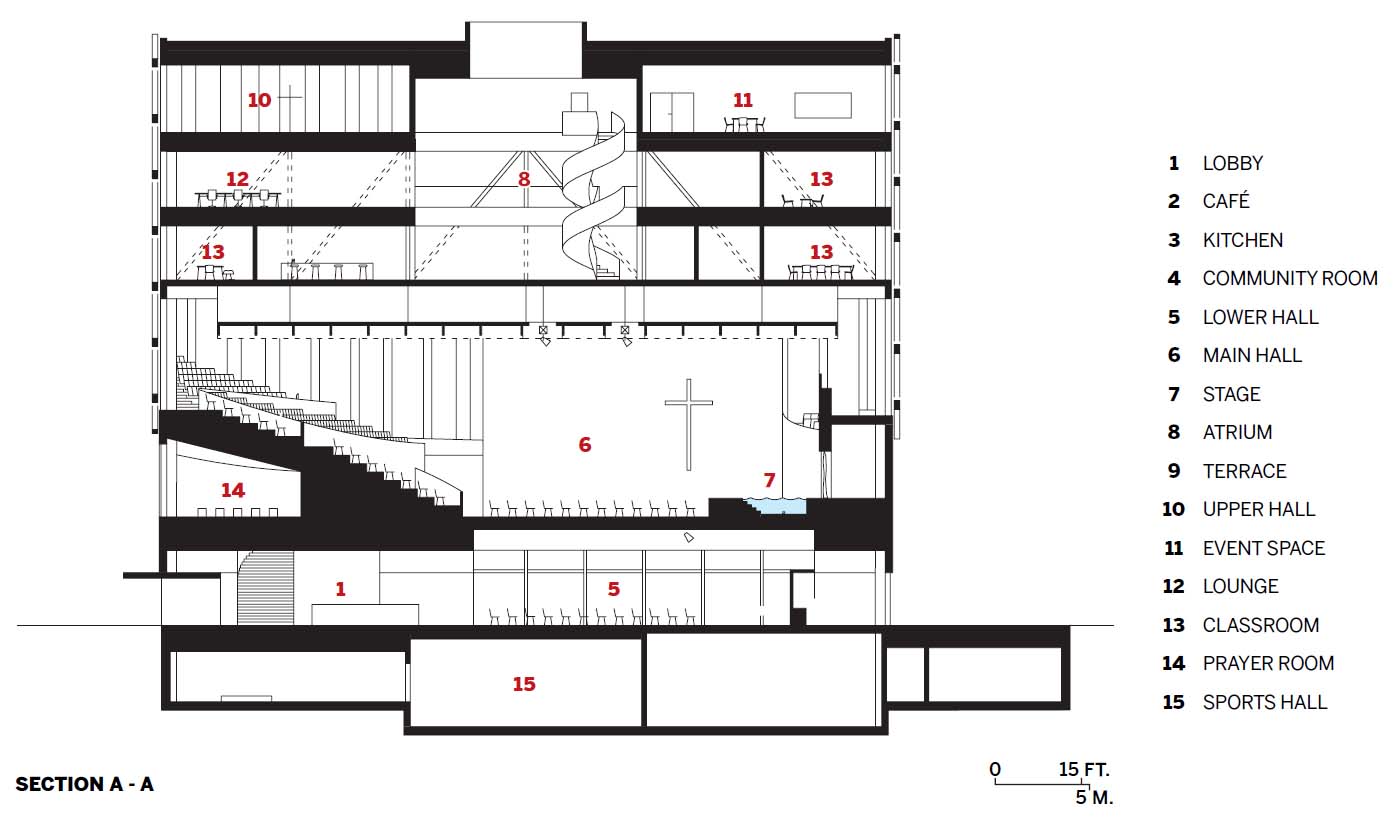

Click section to enlarge

Credits

Architect:

Elding Oscarson — Jonas Elding, Johan Oscarson, partners in charge; Alexander Lundmark, project architect

Engineers:

Contruster (structural); DIFK Florian Kosche (structural concept); LW (facade); Bengt Dahlgren (mechanical); BA Elteknik (electrical)

Consultants:

Jan-Inge Gustafsson, Norconsult (acoustical); Johan Lidström (lighting); CONFIRE (fire safety)

General Contractor: BRA Bygg

Client:

Smyrnakyrkan Pentecostal Parish

Size:

118,000 square feet

Cost:

$28 million (construction)

Completion Date:

October 2023

Sources

Facade:

CEOS Accoya, Reynaers, Purso

Glazing:

Saint Gobain, Guardian

Doors:

Reynaers, Swedoor