Adaptive Reuse Projects by PRO and OMA Anchor a Burgeoning Arts District in Detroit

Detroit

When looking to expand, most commercial art galleries knock down a couple of walls or open a satellite location in an up-and-coming neighborhood where the rent is cheap and foot traffic is promising. Anthony and JJ Curis, the husband-and-wife collectors whose flagship gallery, Library Street Collective, is a mainstay of the downtown-Detroit cultural scene, opted to take a decidedly more radical approach by laying the foundation for a nascent ground-up arts district in a relatively sleepy corner of the city. In the East Village neighborhood, the Curises not only established a backdrop in which to stage larger, more ambitious exhibitions but to grow the gallery’s public programming and community-building efforts, all the while providing a critical asset to the city’s creatives and arts nonprofits: raw space.

It doesn’t hurt that the pioneer-ambassadors of this new enclave, dubbed Little Village, have backgrounds in real estate and hospitality, or that the Curises tapped a pair of architecture firms known for adaptively reusing spaces as art venues. Brooklyn’s Peterson Rich Office (PRO) and the New York studio of OMA have designed the first two of what will eventually be multiple venues spread across a section of the neighborhood enveloped by swaths of urban prairie and dotted with abandoned buildings awaiting new use.

Opening this month as an anchor project of the Little Village master plan developed by PRO and New York–based multidisciplinary design firm OSD is the Shepherd, a multifaceted arts space housed within the former Good Shepherd Church. Dedicated in 1912, the Romanesque-style Catholic house of worship was shuttered by the Archdiocese of Detroit in 2016. As PRO’s Nathan Rich—who presented the project at RECORD’s 2023 Innovation Conference alongside fellow founding partner Miriam Peterson—explains, the building’s role as an “anchoring institution” within the East Village remains much the same in its second life but minus the incense and kneelers. “The Shepherd is still going to bring people together—not around religion, but the arts,” he says.

1

2

The Shepherd hosts a rounded steel stairway to the mezzanine level (1) and Little Village Library (2). Photos © Jason Keen, courtesy Library Street Collective, click to enlarge.

Installation view of Play Patterns II (2011), a mixed-media collage by Charles McGee in the Shepherd’s main gallery. Photo © Jason Keen, courtesy the artist’s estate and Library Street Collective

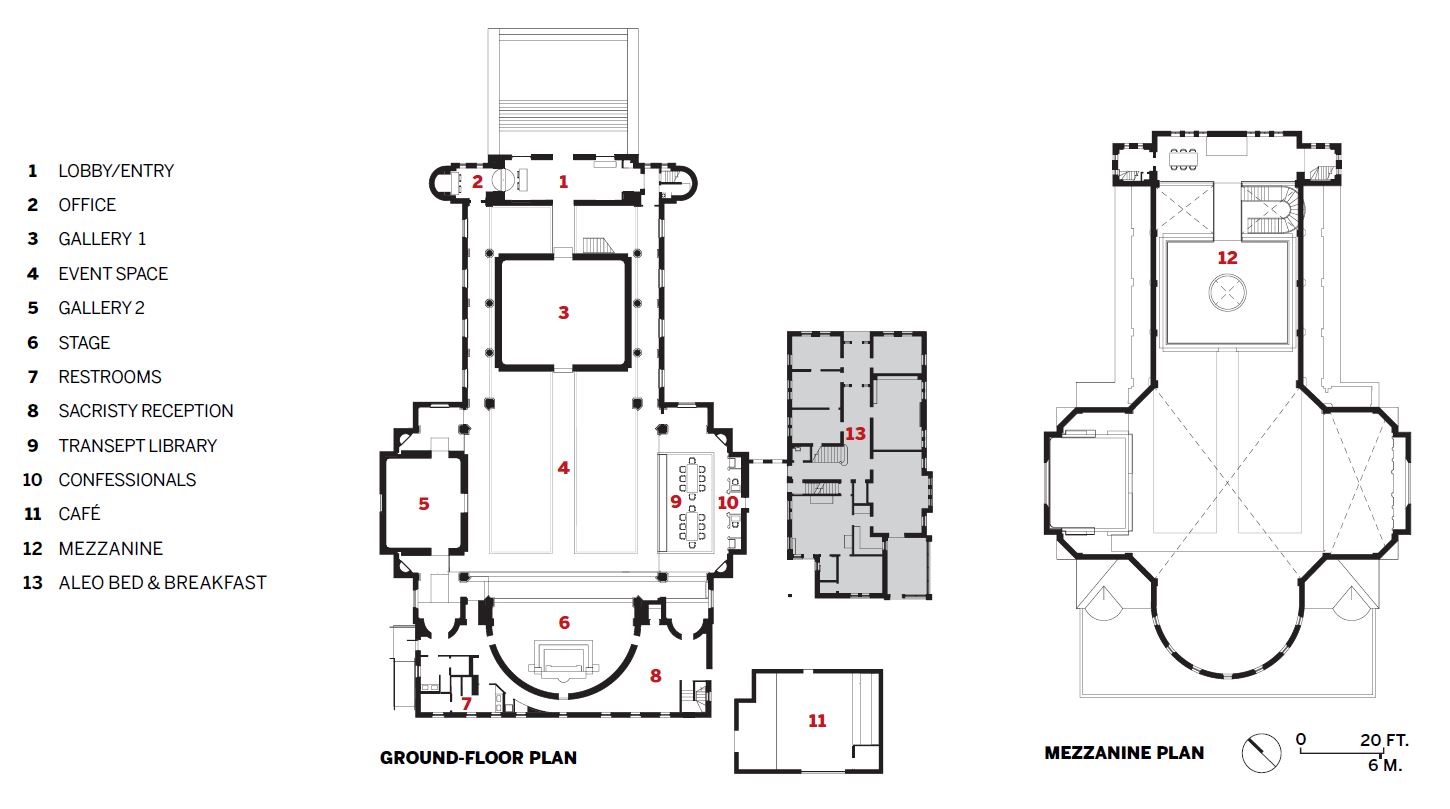

The exterior facade of the historic church, which was in good condition when the project commenced, was largely preserved; the sole intervention by PRO was the addition of a thin weathering-steel “halo” above the front entrance, subtly hinting that something inside has changed. And indeed it has—gone are the pews, a cantilevered choral mezzanine, hanging light fixtures, religious iconography, and non-original ornamentation. Inserted into the light-filled space are two white-cube galleries hosting the Shepherd’s inaugural exhibition, a survey of late artist Charles McGee, presented in collaboration with the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit. At 1,200 square feet, the main volume, steel-framed and finished in textured plaster, is situated in the central nave, punctured by an oculus that provides views up to the church’s soaring, vaulted ceiling. Framing the oculus is a newly created mezzanine level providing flexible programming space. Half the size of its counterpart, the second gallery is in an adjacent transept. Meanwhile, the church’s other transept has been reimagined for a branch location of the Black Art Library curated by Detroit arts-educator Asmaa Walton. Among the interior elements that have been preserved are floor tiles produced by Pewabic Pottery, a historic Detroit ceramic studio located just blocks away from the Shepherd campus.

There are clever moments throughout. The church’s confessional booths have been repurposed as multimedia listening nooks for the library; in a Scooby-Doo–esque touch, a revolving bookcase provides camouflaged secondary access to a tucked-away office; and an adjacent garage, which once housed the hallowed vehicles of resident priests, will be converted into a cocktail bar named Father Forgive Me. That cheekily monikered project is just one of several hospitality elements of Little Village. Housed within the church’s former rectory is ALEO, an art-stuffed bed-and-breakfast. Across the way, a pair of residential structures has been rehabbed—and linked by a two-story deck—by Detroit studio Undecorated to create BridgeHouse, a commercial venue focused on the culinary arts.

The BridgeHouse looks out on a skate park. Photo © Jason Keen, courtesy Library Street Collective

Major elements of the immediate church grounds and surrounding block, resuscitated by OSD founder and creative director Simon David and his team, are a sculpture garden—named in honor of Charles McGee, and permanently featuring large-scale work by him—and a skate park, designed by Tony Hawk and artist McArthur Binion. There’s also the Nave, a forlorn alleyway-turned-pedestrian promenade that connects the new campus to the neighborhood on what was once an unwelcoming and uneven mess of weeds and surface parking lots. Along with improving accessibility to the site, acknowledging its context was key. “You see this texture in the neighborhood of overgrown lots and broken glass and masonry— those things were beautiful to us as well,” says David. “We tried to harness that earthiness and decay and reinvention—so much the story of Detroit—and turn them into design.”

To that effect, recycled-glass mulch found in a meditation loop encircling a swath of open lawn mirrors the colors found in the stained glass of the church; the paving is made from reground brick salvaged from the ruins of an old convent located across the street from the Shepherd. (In a project now under way, led by Lorcan O’Herlihy Architects, a portion of that crumbling structure has been retained, and the site will be transformed into the new home of Library Street Collective’s sister gallery, Louis Buhl & Co.)

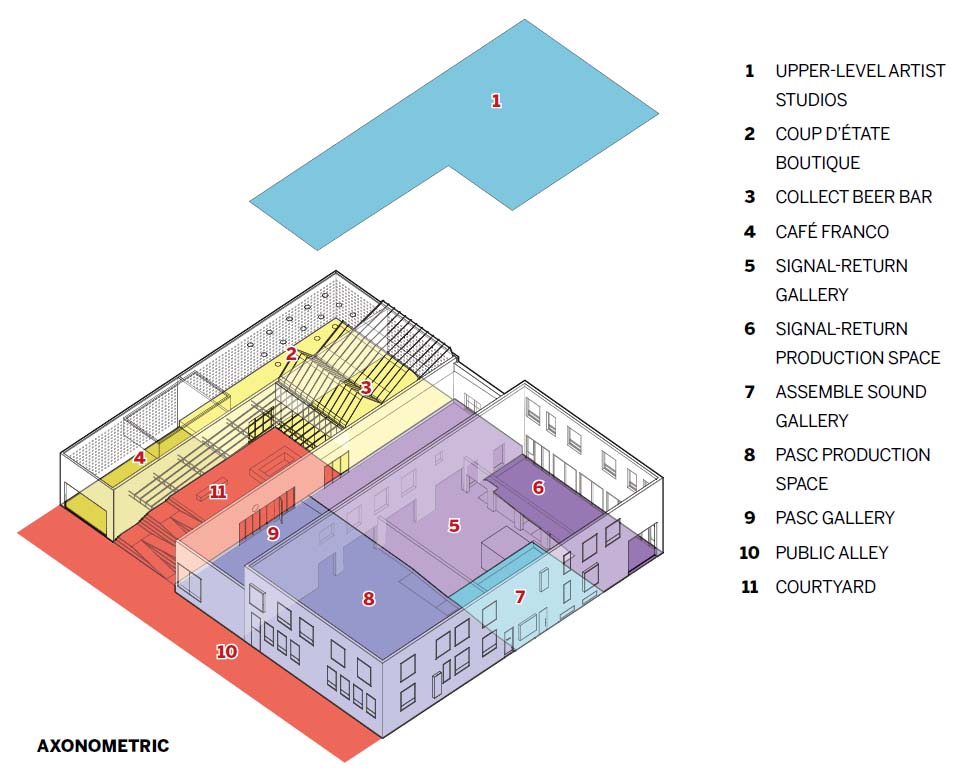

A five-minute walk from the church grounds at the corner of McClellan and Kercheval Avenues is another building revived as a mixed-use art space. Dubbed Lantern, OMA’s contribution to Little Village is a 23,850-square-foot project that encompasses an assemblage of three connected structures that previously housed a commercial bakery and warehouse. Each section of the tripartite building was built in a different era and with different materials, leaving the entire complex in varying states of disrepair—the southern volume, a concrete-block structure, was completely missing its roof. As partner-in-charge Jason Long explains, this provided a poser unlike adaptive-reuse projects he’s worked on elsewhere (POST Houston, for instance, and an outpost of the Centre Pompidou in progress in Jersey City, New Jersey). “Grappling with how to deal with the facade, roof, and height differences was a bit more complex than those projects,” he says, also noting that another challenge arose from accommodating multiple tenants with distinct needs. “A large part of the thinking was trying to orchestrate where tenants could be, and how the various entries and moments of connection could make the whole complex work together.”

3

South facade view of Lantern at night (3). View of Lantern from Amity St. and McClellan Ave. (4), including Signal-Return (5) storefront. Photos © Jason Keen, courtesy Library Street Collective

4

5

As for Lantern’s current tenants, they include Signal-Return, a nonprofit letterpress print shop, and PASC, an organization whose new space in the building will be Detroit’s first studio and gallery dedicated to artists with developmental disabilities. Work is set to complete later this year on the 4,000-square-foot southern space, which will be home to a boutique, bar, and café, and which lends the project its name: in lieu of windows punched into the facade, the structure’s CMU walls are perforated with 1,353 holes, each waterproofed and filled with two glass pavers, inside and out. At night, these glow, transforming the building into a neighborhood beacon. At the rear of Lantern is a public outdoor courtyard. “All the programs essentially feed into it, partly to provide accessibility to them but also so the different tenants have a place to come together,” says Long.

Lantern’s rear public courtyard, with tiered seating. Photo © Jason Keen, courtesy Library Street Collective

With the Shepherd campus and Lantern now mostly complete, there is the question of whether out-of-town art hounds, or even locals, will make the trek to an emerging cultural district removed from Detroit’s downtown core—it could prove to be a tough sell. In the meantime, the Curises are moving ahead with other efforts in the neighborhood, including the revamp of the Stanton Yards marina into a park-studded 13-acre riverfront destination. Led by OSD in collaboration with SO–IL, the project includes a new ground-up building as well as an adaptive-reuse component that will entail the transformation of four existing commercial buildings for public use. This will no doubt continue to attract architectural talent wishing to take part in what Miriam Peterson calls a collaborative and “almost curatorial approach to developing the site,” she says. “The project is, in a sense, like a big group show.”

Click plans to enlarge

Click drawing to enlarge