Landscape

A Pair of Hilltop Parks by Hood Design Studio Offer Sweeping–and Rarely Seen–Views of San Francisco Bay

San Francisco

Yerba Buena Island’s Panorama Park, features Hiroshi Sugimoto’s Point of Infinity, with views of the Bay Bridge and San Francisco skyline. Photo courtesy Yerba Buena Island

Architects & Firms

For many Bay Area residents and visitors, the craggy outcrop in the middle of San Francisco Bay known as Yerba Buena Island is mostly experienced while inside an 88-year-old concrete tunnel. The 10-lane, double-deck Yerba Buena Tunnel carries Interstate 80 through the middle of the island, linking the eastern and western spans of the San Francisco–Oakland Bay Bridge. The 150-acre island—formerly the site of a U.S. Navy training station and currently home to a modest Coast Guard outpost—has long been utilized as a crucial piece of transportation infrastructure and is now in the infancy of its next use: a residential enclave unlike any other in the housing-strapped region.

Along with Treasure Island, its more sprawling neighbor constructed for the 1939 World’s Fair, Yerba Buena Island is the focus of an ambitious scheme slated to be the largest housing development in Northern California, with 8,000 units planned in total, roughly a quarter of them affordable. Among the first elements to be completed are Yerba Buena’s public green spaces, including a pair of newly unveiled parks, by Oakland-based Hood Design Studio, situated atop the highest point on the island.

The Signal Point overlook features a large circular seating area. Photo courtesy Hood Design Studio

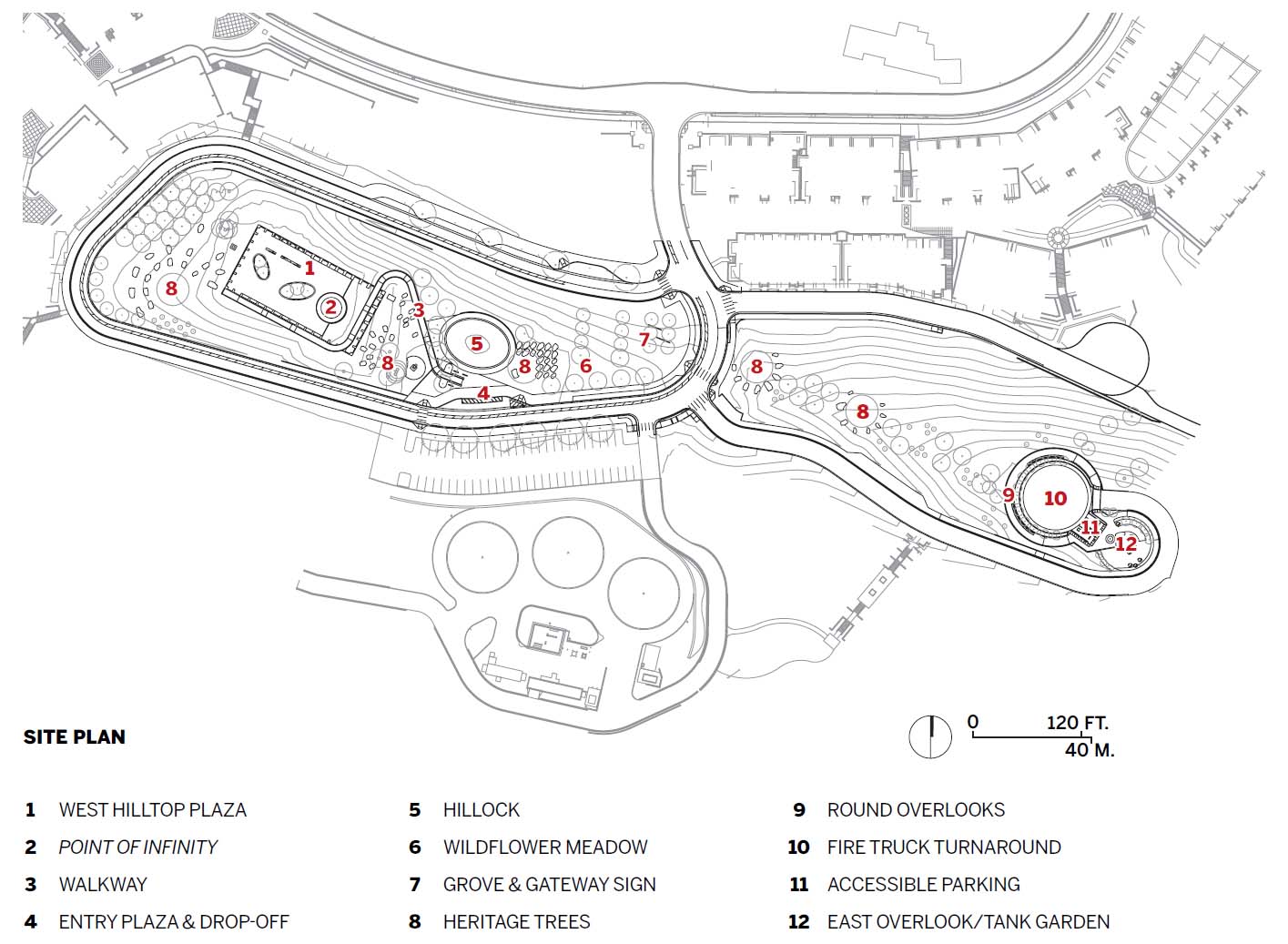

Sliced by Yerba Buena Drive, the two parks—Panorama Park to the west and Signal Point to the east—designed as “passive” space, so as not to undermine the main attraction: the previously rarely seen vista of the bay from the apex of this once largely inaccessible island. “You’re basically sitting on top of the bridge,” says Alma Du Solier, landscape architect and studio director at Hood Design Studio. “The views are so impressive that it almost feels like you can’t do anything other than sit and admire them.” The design, she says, shifted through the process to explore how to best take advantage of that experience. A grassy knoll, located at the middle of the site near a wildflower meadow and gridded cluster of coast live oaks, is the only space with the potential for frolicking. Accordingly, seating is abundant and includes a large circular bench crafted from durable ipé at Signal Point’s overlook, as well as benches fabricated from eucalyptus wood salvaged from construction projects under way across the island. Strategically placed boulders, excavated from nearby sites where the island’s hot-selling condo communities have gone up, also provide places to rest and take it all in.

A curving raised walkway extends from an entry plaza and partially encircles Panorama Park. Photo courtesy Yerba Buena Island

Although structures comprising the old naval base have long since been demolished, remnants of the site’s former life do still exist, including a 2 million-gallon reservoir built into the hillside in 1918. Accessible via a winding elevated walkway, the preserved tank’s lid has been cut to create a perimeter wall around Panorama Park’s observation plaza. Positioned atop a relic that Du Solier calls the “genesis of the project,” the plaza is also the site of Point of Infinity, a monumental sculpture-cum-sundial by Japanese photographer and architectural designer Hiroshi Sugimoto. As Du Solier explains, the space was designed prior to the decision to place the 69-foot-tall, tapering stainless-steel sculpture there, leading to some modifications. “There’s been some confusion among the public about whether the sculpture is the site and we were designing for it to be in a beautiful place. It’s really kind of the opposite,” she says: what they crafted the site for was to foster a sense of discovery. She hopes visitors feel that as they set foot on—and relish the awe-inspiring views from—the pinnacle of an island previously unknown to all but a few.

Click plan to enlarge