Bahrain's Pearling Path Protects and Revives a Defunct Trade's Architectural Legacy

Bahrain

Architects & Firms

“The very highest position among all valuables belongs to the pearl,” wrote Pliny the Elder. “But those are most highly valued which are found [in] the Persian

Gulf . . .” To the Roman chronicler’s fellow citizens in the first century CE, and to their contemporaries throughout the known world, the tiny archipelago of Tylos—known today as Bahrain—was famous for the treasures hiding in the shallow, cloudy waters that surround it. Sustained by its signature product, and by a market that was global in reach long before the advent of globalism, the city-state off the coast of the Arabian Peninsula continued to thrive for nearly two millennia after Pliny’s time.

Until, unfortunately, the emerging global economy caught up with it. “Everything here was built around the industry,” says architect Noura Al Sayeh. “And then, in the 1930s, it collapsed.” After the Japanese developed a method for cultivating artificial pearls, Bahrain found itself in eclipse—but, as Al Sayeh explains, the extraordinary urban culture that the pearling business had helped create remained very much intact. “So many of the buildings here represent some aspect or other of that society,” she says. It’s a legacy that Al Sayeh—alongside a lengthy list of collaborators—is now endeavoring to preserve and to celebrate.

In a sea of historic buildings, the Pearling Path’s new structures command attention. Photo © Iwan Baan, click to enlarge.

Officially open to the public this spring, the Pearling Path is a more than two-mile-long corridor of historic landmarks, new infrastructure, and hybrid contemporary-and-restored buildings, running from the old harbor through the bustling heart of Muharraq, the older, denser twin city to the current capital of Manama. Following extensive advocacy by Bahrani officials, including former prime minister Sheikh Khalifa bin Salman Al Khalifa, the United Nations declared the ancient pearl-trade district an official World Heritage Site in 2012.

Two years prior, Al Sayeh had helped organize Bahrain’s debut pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale, marking the start of her still-ongoing role as Head of Architectural Affairs for the country’s Authority for Culture and Antiquities. The Pearling Path represents the cumulative results of Al Sayeh’s now 14-year effort to transform how Bahrain understands its own past, and how the world understands Bahrain. “In terms of urban regeneration, it’s been such a huge opportunity,” says the architect.

Four parking structures; 17 public squares; a pedestrian bridge; a visitors center: the new construction along the Pearling Path is intended to complement the 15-odd original houses, mosques, and marine oyster beds listed in the UNESCO-designated area, providing extra amenities and points of interest for visitors and locals alike. Dividing the sizable brief into chunks, Al Sayeh parceled them out to various firms from around the world, largely drawn from her extensive personal network of friends and colleagues in Western Europe. Her architects responded with an almost alarming degree of formal fantasy and conceptual ambition, apparently spurred on by both the possibilities and the constraints of the particular locale and conditions.

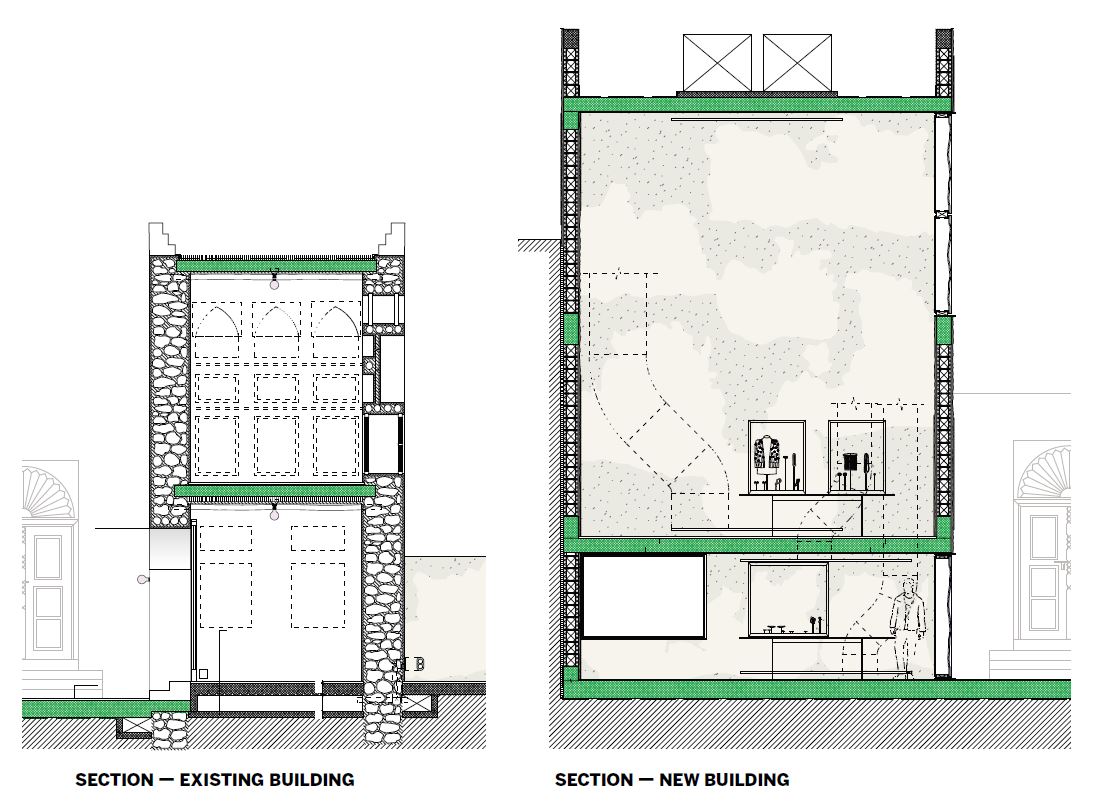

“Because Bahrain is a place of such few resources, you have to be very inventive in terms of materials and structure,” says Anne Holtrop, describing the overall process as “really tricky.” The Dutch-born architect is speaking of his own multipart commission comprising a new portion of the Souq Al Qaysariya commercial facility, work on preexisting market structures nearby, and the renovation and exhibition design of the revitalized Siyadi Majlis Pearl Museum. Ranging from the quasi-Brutalist sophistication of the concrete-clad souk to the subdued, delicate feel of the museum, Holtrop’s job was made all the trickier for having to be coordinated with the other project participants, in particular the participant in chief, Al Sayeh, who also happens to be Holtrop’s wife and longtime business partner.

1

2

The souk’s smooth concrete erodes at the edges (1). Similarly, the Pearl Museum (2) has cladding and inner walls (3) that modulate between flat and textured. Photos © Iwan Baan

3

Other team members faced different challenges. “I didn’t want to just export an architecture,” says Swiss architect Christian Kerez. Tasked with creating the parking structures for the largely pedestrian-oriented redevelopment, the designer had to strike a compromise between the Middle East’s growing dependence on cars and the historic fabric of Muharraq that the Pearling Path is meant to protect. As it happens, it was a problem Kerez was eager to take on. “Parking garages are a neglected typology,” he says. “I thought it would be fascinating to do one.” The first of the projects to be completed, a four-story complex with space for over a hundred vehicles, slips discreetly into its urban surrounds with exquisitely thin concrete slabs, each one with a slightly different improbable geometry from the next. Appearing to billow in the cool Gulf breeze, the effect is as sophisticated as any of Miami’s high-design garages from recent years, yet created (as Kerez explains) using standard regional practices and formwork.

4

Concrete surfaces split to form multiple parking levels (4), while a stair corkscrews through them to offer vertical circulation (5). Photos © Iwan Baan

5

From Belgium, OFFICE KGDVS was brought aboard (along with landscape practice Bureau Bas Smets, a fellow Brussels firm) to assist in the creation of the Path’s semiconnected sequence of public plazas, as well as the design of a footbridge passing over a busy automotive thoroughfare (produced in partnership with local firm Ismail Khonji Architects). “It was very important to create spaces that would not just reflect the pearling tradition, but that would also be used by the people living there,” says OFFICE’s Jelena Pancevac. Picking their way through the narrow streets, the team of KGDVS and Smets made a series of minute, strategic interventions, four of them realized to date, producing “green oases” of seating and plantings embedded in the warren-like cityscape. For the viaduct, minimal impact was also key; the span is supported by simple concrete piers that rhyme with the coral-laden stone of the nearby buildings, forming the last piece of the maze between the waterfront and the city.

6

OFFICE KGDVS and Bureau Bas Smets partnered on a footbridge (6) and public spaces (7). Dar Al Jinaa is dressed in a fabriclike chain mail (8). Photos © Iwan Baan

7

8

In such an immense labyrinth, there are bound to be a few confusing twists and turns—and not just in the physical sense. “It’s a complicated project,” Al Sayeh admits, “one that intersects a lot of other things.” Besides the abovementioned studios, a whole cavalcade of additional firms—Valerio Olgiati for the Visitor’s Center, Formafantasma for three installations in the restored houses, and a grab bag of engineers, restoration specialists, and consultants—have been involved in the Pearling Path, which also happens to sit adjacent to a number of projects (most notably OFFICE’s striking Dar Al Jinaa events space) not technically part of the scheme. Still more designers may (or may not) be drawn into the project in the future, its scope remaining surprisingly hazy over a decade into its construction. And then there’s the uncertain matter of why, save for a few Bahrani collaborators like Khonji, the majority of the architects have come from abroad, most of them from the same rarefied avant-garde stratum familiar to attendees of certain fairs, festivals, and -ennials of assorted denominations. It’s a question that might be paired with the observation that, owing to Bahrain’s small size, almost the entire workforce for the Pearling Path had to be imported, largely from South Asia.

But then these things are not exactly new. “This isn’t just about tourism,” says Al Sayeh. As its once-profitable oil sector continues to decline (a 6 percent drop in output every year since 1970), Bahrain has been attempting to revive its age-old pearling industry, establishing a reputation for both organic harvesting techniques and for expertise, with ultramodern analytical facilities and a rapidly burgeoning jewelry fair. Trumpeting the country’s association with those gleaming balls of calcium, the Pearling Path and its high-flown, forward-looking new architecture is part of an attempt to reassert Bahrain’s status as a center for the sale and production of luxury goods, putting it back on the map right where the Greeks, Romans, and Persians had it. If the project’s background definitely feels more global than local, the same could be said for Bahrain.

Click sections to enlarge

Click drawings to enlarge

Siyadi Majlis Pearl Museum | Credits

Architect:

Studio Anne Holtrop — Anne Holtrop, principal; Mohammad Salim, Constança Girbal, project architects

Architect of Record:

Ismail Khonji Associates

Engineers:

Ismail Khonji Associates (structural); Sayed Jaffar Majeed (m/e/p)

Consultants:

Aïnu (exhibition); Studio Jonathan Hares (graphic design)

General Contractors:

Amoayyed Interiors (civil); Bakhowa Group (interiors); Restaura (exhibition); Group Galrão (stone)

Size:

14,200 square feet

Cost:

$1.8 million (construction)

Completion Date:

February 2024

Parking Garages | Credits

Architect:

Christian Kerez — Christian Kerez, principal; Caio Barboza, project architect; Dennis Saiello, Lisa Kusaka

Engineer of Record:

Arsinals Engineering Design

Engineers:

Ferrari Gartmann (Plot A); Neven Kostic (Plot B); Monotti Ingegneri Consulenti (Plots C and D)

Consultants:

Baukolorit (concrete); Catherine Dumont d’Ayot (landscape, Plots C and D); LK Argus, Alden Studio (traffic); Siegrun Appelt with Mathias Burger (lighting)

Pearling Path and Footbridge | Credits

Architect:

OFFICE KGDVS — Kersten Geers, David Van Severen, Federico Perugini, Anna Andrich, Nenad Đurić, Alexandra Paritzky, Denis Glauden, Paul Christian

Architect of Record:

Ismail Khonji Associates

Landscape Architect:

Bureau Bas Smets

Engineers:

Gulf House Engineering, Transsolar

Dar Al Jinaa Events Space | Credits

Architect:

OFFICE KGDVS — Kersten Geers, David Van Severen, Santiago Giusto, Federico Perugini, Anna Andrich, Nenad Đurić, Paul Christian, Denis Glauden, Alexandra Paritzky

Engineers:

Emaar Engineering

Size:

6,450 square feet

Cost:

$850,000 (construction)