Multifamily Housing 2024

5468796 Architecture Adjoins a Pair of Sleek Apartment Buildings to a No-Frills Historic Restoration Project

Winnipeg, Manitoba

Architects & Firms

At the turn of the 20th century, Winnipeg was Canada’s boomtown. Already a longtime trading post, courtesy of its prime location at the fork of the Assiniboine and Red rivers, the opening of the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1881 made the city a leader in international grain markets and the agricultural center of the country, garnering it the nickname the “Chicago of the North.” During this era, the Exchange District, a 20-block area nestled in the curve of the Red River, emerged as the budding metropolis’s commercial and cultural core, home to the city’s prominent financial institutions, businesses, and nightlife. Though Winnipeg’s industrial prominence has faded over the course of a century, reminders of this golden age are visible in the Exchange’s cobblestone streets, narrow alleyways, and bevy of architectural treasures, including terra-cotta-clad Chicago-style skyscrapers and stately stone-and-brick warehouses.

One less-glamorous remnant is a single-story pumping station, a squat brick building occupying a 4,500-square-foot site in a prime location near the riverfront. Originally built in 1906 to aid in fighting the frequent fires that afflicted the district, the original building served its civic duty for decades—distributing water from the river to over 70 fire hydrants in the downtown area. In 1986, however, the dated facility was shuttered by the city.

1

2

The jet-black steel facades and structural elements of Pumphouse’s residential buildings (1, 2, and top of page) reference the industrial structure’s preserved interior (3). Photos © James Brittain, click to enlarge.

3

After years of limbo, a technically ambitious design by 2011 Design Vanguard 5468796 Architecture, completed earlier this year, allowed the pumping house to step up for the city once again, procuring a new role in a new century. Taking an economically and environmentally frugal approach to preservation, the Winnipeg-based firm integrated an office and restaurant within the existing building and flanked it with two five-story housing blocks.

Founded in 2007 by Johanna Hurme and Sasa Radulovic, 5468796 has a wide swath of Winnipeg housing projects under its belt and is known for tackling complex commissions on tricky sites. Called Pumphouse, this project represents a culmination of the many lessons learned by the firm over years of practice, from grappling with the historic district’s complex building codes to juggling financial constraints and varied programmatic needs. “We pulled out every tool in our kit to make this project feasible,” says Hurme. “To us, that means maximizing the quality of life for the inhabitants while creating a vital player in the cityscape.”

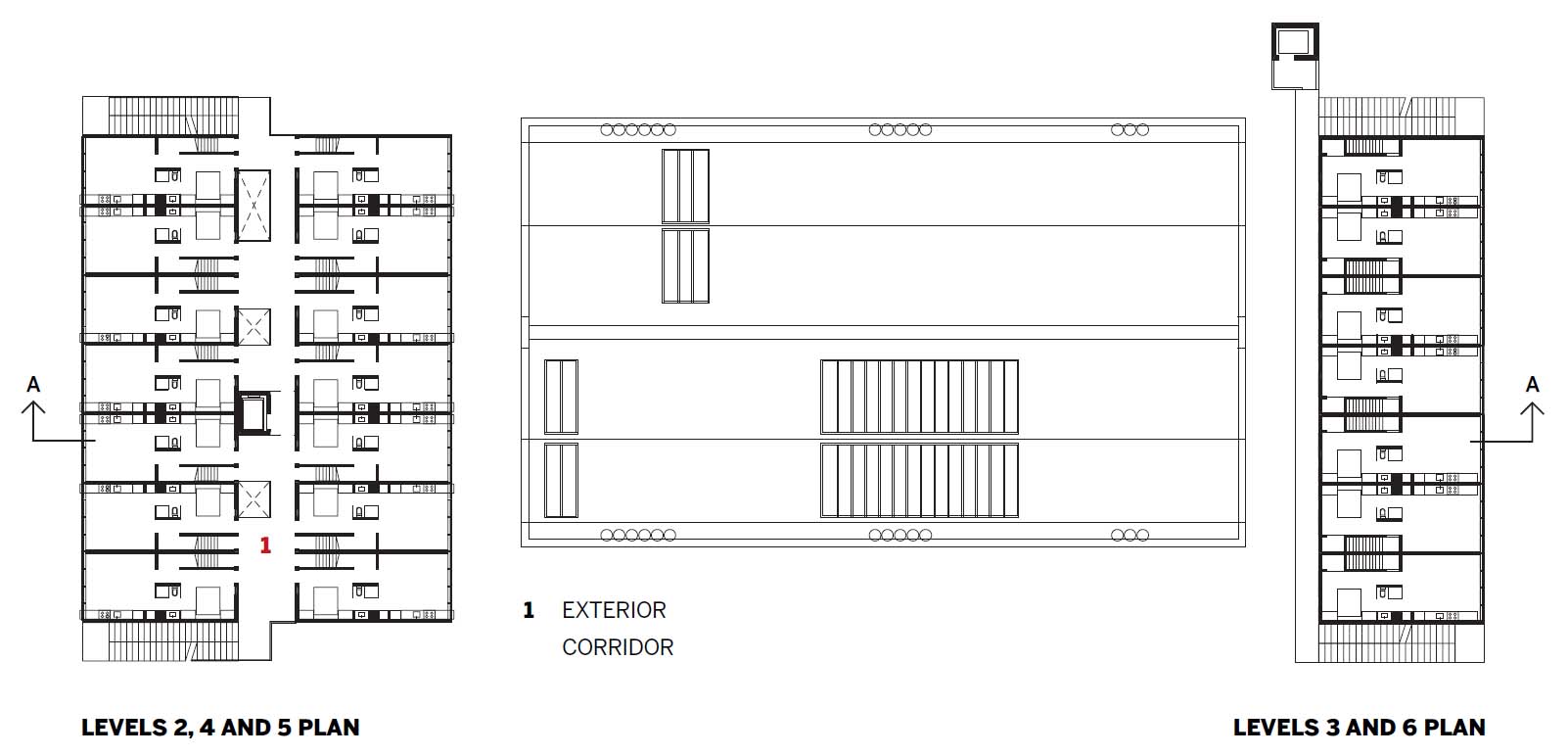

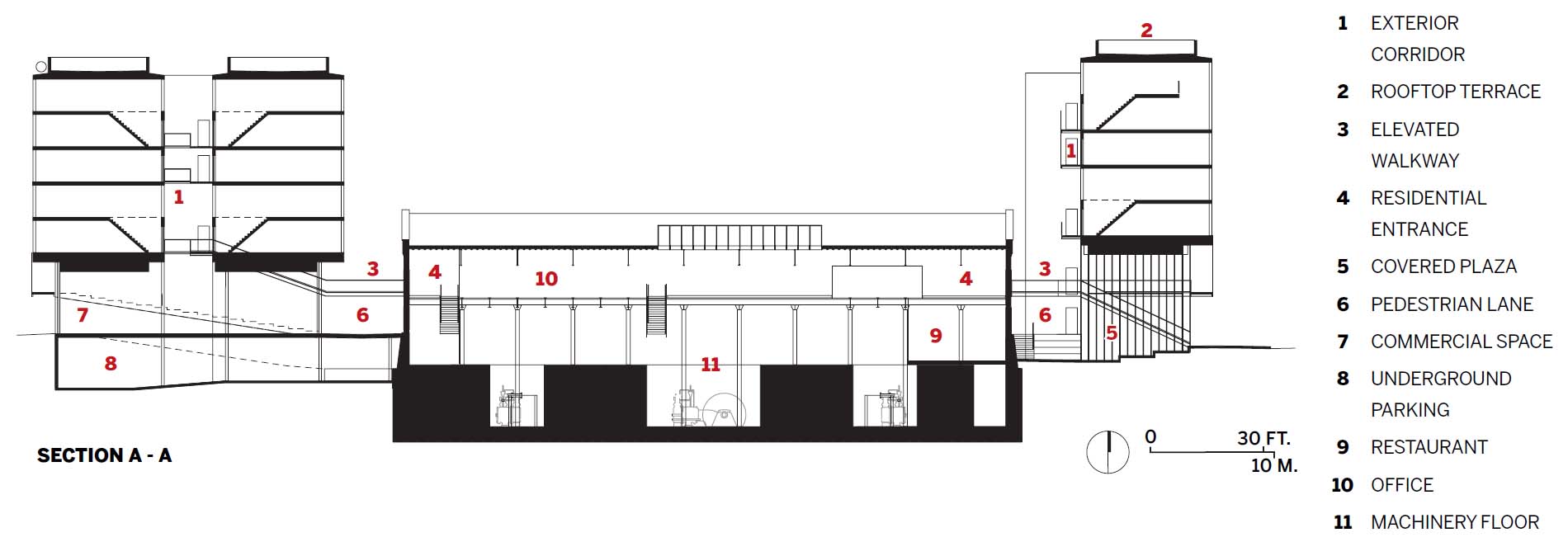

Elevated 30 feet above street level on concrete plinths and steel stilts, the project’s timber-framed residential components are clad in jet-black corrugated metal, offering a severe contrast to the beige solidity of the heritage building sandwiched between them. However, the firm’s thoughtful material choices and intricate spatial solutions reflect and extend the central preservation project’s guiding principles.

The 28-unit building to the east is slotted into a narrow, formerly vacant parcel of land alongside Waterfront Drive, a bustling thoroughfare where well-stocked trains once trundled on now-demolished railroad tracks. The western end of the site hosts two adjacent buildings, connected by a shared corridor, and containing a total of 63 residential units, with a commercial space (currently occupied by a hair salon) and public amphitheater nestled below.

Image courtesy of 5468796 Architecture

The design concept turned a typical North American housing block inside out, emphasizing and externalizing circulatory corridors. This typology is particularly unusual in Winnipeg, which endures long subzero winters and high winds, but was central to the project’s public-facing philosophy. “Having grown up in European multifamily housing, Johanna and I understand that community happens in these shared spaces,” says Radulovic. “Placing the circulation on the outside of the building fosters connections among the people in the building and back to the city itself.”

The cantilevered open-air stairways are protected with a fine-grain metal mesh and are accessible via pedestrian bridges that lead from the restored pumping house’s interior, wrapping around the building’s volumes, and into shared corridors on the second, fourth, and sixth levels. This “skip-stop” arrangement was made possible by alternating two- and one-story residential units and cut the building’s total area by 10 percent.

All the apartments are, appropriately, railroad style, but the exterior corridors enable windows within the centrally placed bedrooms, allowing cross ventilation and an abundance of natural light. Each suite is capped with full-height glazing at either end, which frames panoramic views of the city or riverfront. Taking advantage of a building technology as old as the Exchange itself, unit floors and ceilings are made up of unvarnished nail-laminated-timber slabs, lending a touch of visual warmth to the otherwise chromatically austere project. The stairways and corridors use raw and unfinished materials—galvanized zinc, concrete, and aluminum—both visually and physically connecting the new volumes to the pumping house. “Every part of this project is stripped down to its absolute essence,” says 5468796 associate Ken Borton, the project’s design architect.

Units feature floor-to-ceiling glazing. Photo © James Brittain

Since its shuttering almost 40 years ago, more than a dozen attempts have been made to revive the original building. But its heritage status, bestowed in 1982, presented a major development hurdle, mandating the preservation of the pumping machinery, exterior brick walls, windows, concrete foundation, and timber roof. Proposals swirled and floundered around the structure until 2015, when Radulovic and Hurme heard from a friend in local government that the city was moving toward demolishing the structure.

With no brief or commission, the firm took the project on “as a personal challenge,” says Radulovic, first devising a financially and technically viable multipurpose program for the development, and then convincing an existing client—Alston Properties—to build it. Hurme used the term “critical opportunism” to describe the firm’s go-getter approach: “We like to create work for ourselves,” she said with a laugh.

Allocating only $2 million of the project’s $22 million total budget to its adaptive-reuse phase, the firm treated the pumping house as a “found object,” leaving as much of the original structure as untouched as possible. “The history is part and parcel of the building’s narrative,” says Radulovic. “That includes the dust, rust, and patina.”

Open-air walkways connect new construction to the historic pumping house. Photo © James Brittain

The long and narrow pumping house is divided into two gabled bays, each equipped with a 20,000-pound gantry crane running the 150-foot length of the interior. The most glaring design challenge was that its original floor was 18 feet below grade, but the design team realized they could leverage the existing crane system to suspend a “floating floor” over the engine room’s guts, creating a flexible and airy office space (currently leased to a software company). By incorporating full-height glazing into the floor plate’s new interior envelope, this economical design strategy not only preserved the building’s equipment but put it on full display, allowing workers, visitors, and passing apartment residents to peer down into the vast expanse of machinery below. For a more intimate view, the interior walls of the ground-floor restaurant on the building’s east end are also enclosed with glass.

Though visually distinct and spatially separated from the no-frills restoration endeavor they adjoin, Pumphouse’s sleek housing blocks expand the spatial language of the 118-year-old building’s refreshed interior, with the exposed structural elements that lift the building off the ground acting as an extension of the gantry crane structure inside. The web of circulatory corridors stretches the grid of the historic building’s new floor plan outside its original walls, spilling into the residential spaces and even, by creating new public spaces below, onto the surrounding streetscape. The firm’s endeavor simultaneously obscures and illuminates the line that divides public from private and old from new, integrating the project’s spaces fully within the multiple contexts of its program and rapidly developing neighborhood.

Click plan to enlarge

Click section to enlarge

Credits

Architect:

5468796 Architecture

Engineers:

Lavergne Draward & Associates (structural); MCW Consultants (mechanical, electrical, civil)

Consultants:

Scatliff + Miller + Murray (landscape); Crosier Kilgour (energy); GHL Consultants (code)

General Contractor:

Brenton Construction

Client/Owner:

Alston Properties

Size:

18,000 square feet (office and hospitality); 76,500 square feet (multifamily residential)

Cost:

$22 million

Completion Date:

January 2024

Sources

Structural System:

Holz Constructors (nail-laminated-timber floors & prefabricated wood stud walls); Phoenix Iron Works (structural steel); U.S. Aluminum (curtain wall)

Exterior Cladding:

Vicwest (corrugated steel); KlarTech (aluminum)

Glazing:

Duxton Windows and Doors (interior glass); Polygal (skylights)

Conveyance:

Elevators/escalators: Thyssen Krupp (apartment elevators)

Accessibility provisions: Savaria (pumping station lift)

Stairs: Imperial Metal Industries (Interior steel stairs)

Doors:

U.S. Aluminum (entrances); Penner Doors & Hardware (metal doors)