America’s cities and states are increasingly turning toward building electrification as a tool to further decarbonization goals. According to the EPA, building operations account for nearly 40 percent of U.S. energy consumption and approximately 30 percent of greenhouse-gas emissions. Switching over to equipment such as induction stovetops and heat pumps, coupled with the use of renewable energy and efficiency measures, could bring those numbers closer to zero. In the last year, in a riposte to the growing upswell, the House of Representatives passed a bipartisan bill to block the Consumer Product Safety Commission from using federal funds to ban gas stoves, and litigation has turned the courtroom into a battleground in the race to decarbonize.

In April 2023, the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit—the court is headquartered in San Francisco and encompasses much of the western United States—ruled in favor of plaintiff California Restaurant Association against defendant City of Berkeley, which in 2019 had passed the country’s first prohibition on the installation of natural gas pipes in new construction. The Ninth Circuit argued that the local ban is incongruent with the federal government’s Energy Policy and Conservation Act and infringed on its exclusive power to regulate gas appliances. Last May, the City of Berkeley filed a petition for a rehearing and was granted an amicus brief by the Ninth Circuit, though the court ultimately struck down the petition in January.

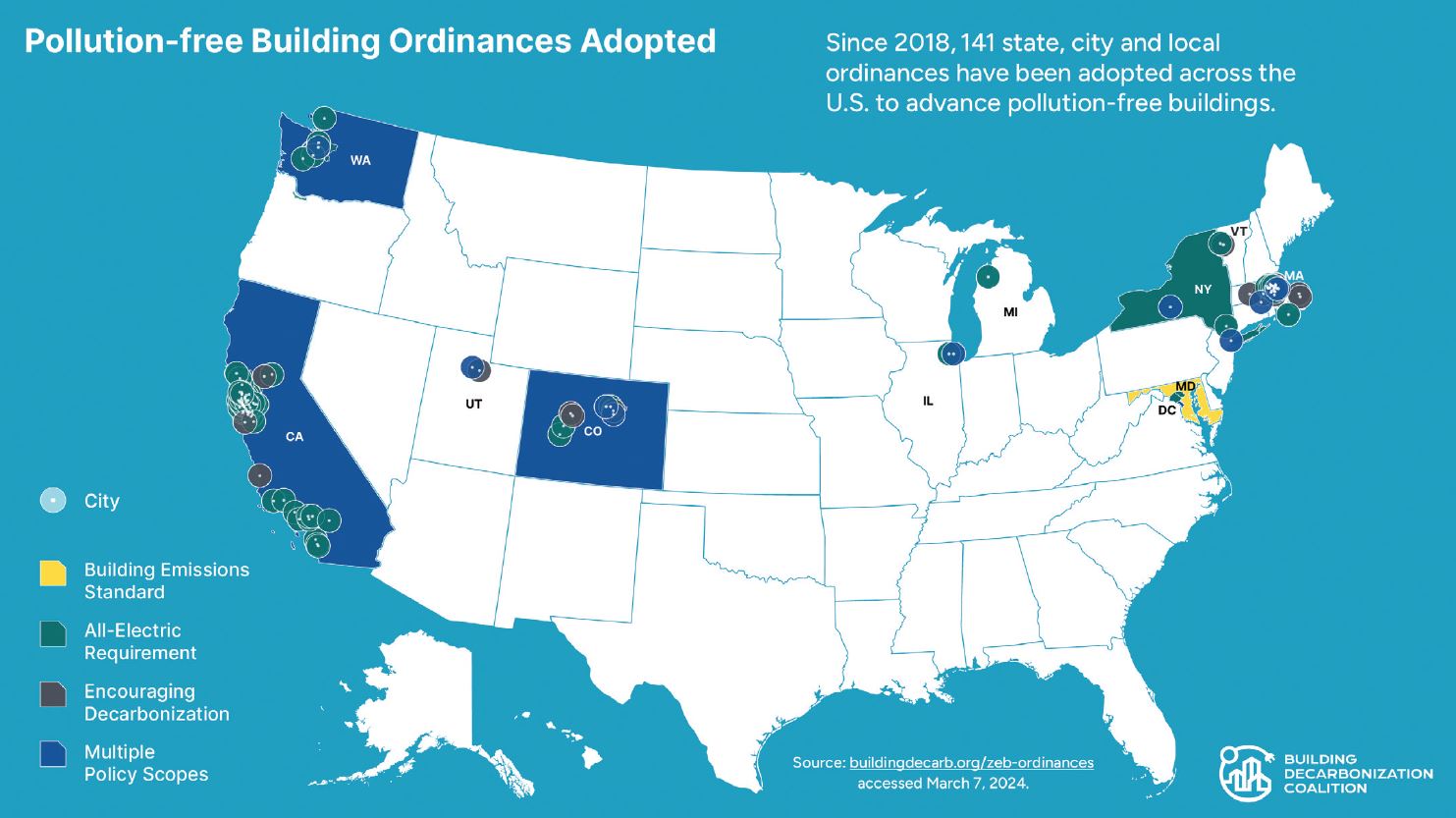

Berkeley is not alone in its attempt to ban gas lines in new construction; dozens of the nation’s cities have followed suit, including New York, Seattle, and San Francisco. States are also joining the fray. Washington updated its building codes in 2022 to require heat pumps in new construction—though, prompted by the Berkeley ruling, it later revised the building code to incentivize electrification rather than prohibit the use of fossil-fuel-burning equipment. New York and California have rolled out similar restrictions, set for 2026 and 2030, respectively. So far, over 100 cities and states have instituted policies to prohibit or discourage the installation of gas lines in new buildings.

Click map to enlarge

What are the implications of the Berkeley ruling and other lawsuits for the country’s decarbonization ambitions? According to Stet Sanborn—a vice president at design firm SmithGroup and a mechanical-engineering and in-house decarbonization expert—the ruling, and similar ones, is likely to have minimal impact on the building industry, as government incentives and market forces are already pushing toward electrification. “The train has already left the station,” Sanborn says. “The gas lobby can go fight city by city, but the momentum is already there, and building electrification is cheaper and safer than the alternative.” Those savings result from the reduced installation and maintenance costs of just the one system, rather than both gas and electric. In terms of safety, houses with gas stoves are estimated to have nitrogen dioxide concentrations up to four times that of electric stoves, increasing childhood asthma risks by over 40 percent.

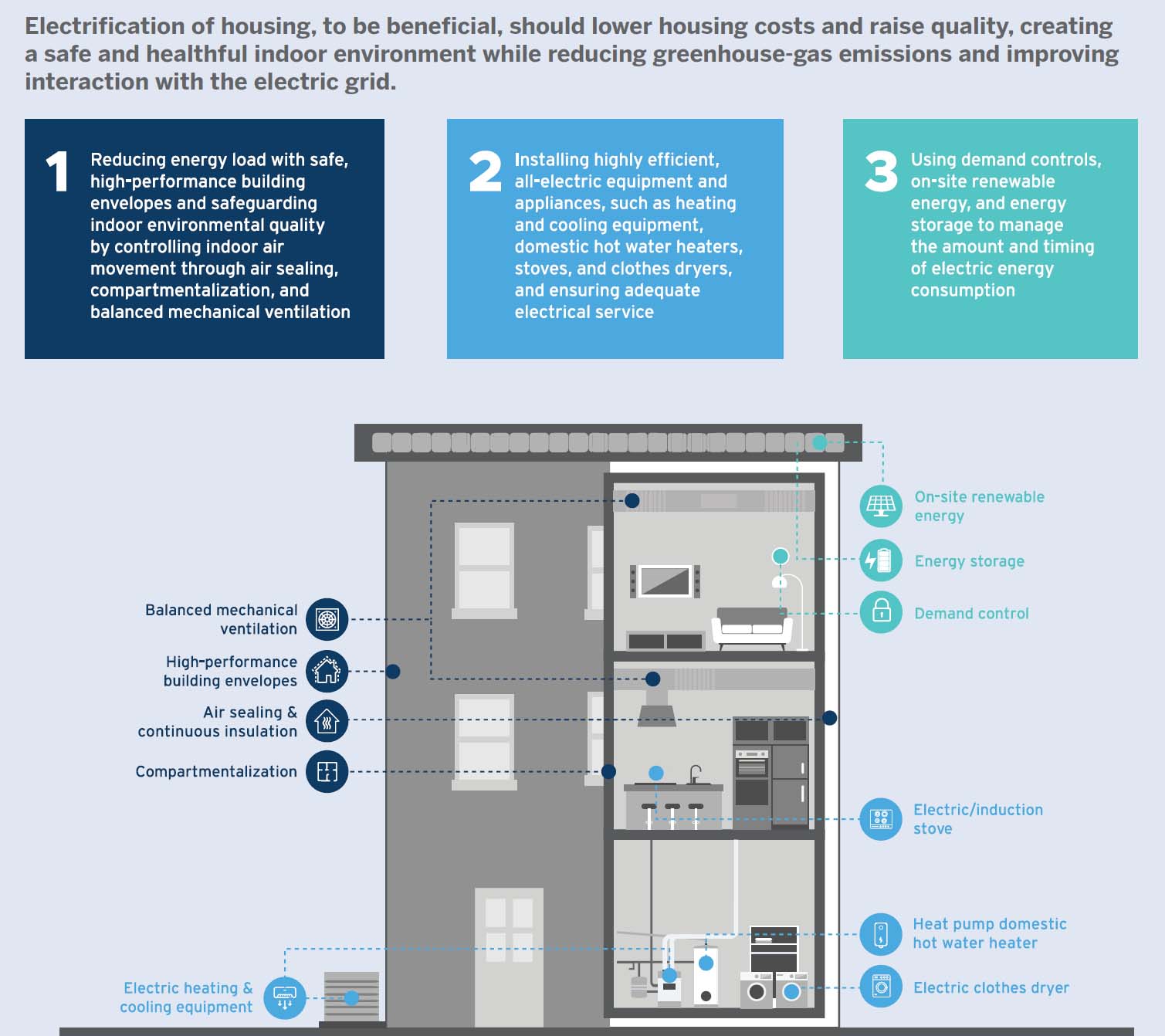

Image courtesy of Rocky Mountain Institute, click to enlarge.

The gathering of speed in the direction of electrification was on full display last September when the United States Climate Alliance, a bipartisan coalition representing 25 states and nearly 180 million citizens, announced alongside the Biden administration that, through a range of incentives, it aims to boost the annual number of heat pumps installed nationwide from just under 5 million to 20 million by 2030.

For Panama Bartholomy, the founder and executive director of the Building Decarbonization Coalition, incentives are all well and good, but without regulation of new gas appliances, there are still several roadblocks, such as so-called “stranded assets,” that could prove stubborn in the years ahead. One example is “the pipe that gets put in the ground now has a life span of up to 80-years. We are knowingly investing in [gas] infrastructure even though we need to phase out fossil fuels within 25 years,” he explains, noting that ratepayers or taxpayers are likely to be on the hook for the gas utilities’ sunken costs. The issue of stranded assets extends to household appliances, such as furnaces and water heaters, or stoves, which have life expectancies of up to 20 years. “You cannot be installing fossil-fuel equipment past the middle of the next decade. That will keep the need for gas to continue flowing through neighborhoods and not allow those places the opportunity to transition to clean energy,” he says.

At the Rocky Mountain Institute, Denise Grab, principal on its carbon-free buildings team, suggests that while the court decision on Berkeley potentially rules out policies directly prohibiting natural gas lines in new construction, there is a grab bag of indirect measures, ranging from building codes to performance and air-pollution standards, that can be strengthened to drive the market in the direction of building electrification. Moreover, the precedent set by the Ninth Circuit may not hold in its peer courts. “There were very strong dissents within the court regarding the decision—which is quite rare—indicating in thoughtful and strong terms why the majority was wrong,” Grab says.

The road to decarbonization in the building industry has many twists and turns, but, on this road, court decisions may prove more of a speed bump than a blockade.