A Public Plaza-Topped Underwater Bike Garage Revitalizes a Neglected Stretch of Riverfront in Amsterdam

Architects & Firms

Those who alight from trains at Amsterdam Central Station are flung into an urban maelstrom. With 200,000 daily riders, the station is a critical hub for trains, but also for trams, ferries across the IJ River, and bicycles, with a key east–west cycling path running parallel to the vast building.

Bicycles, which account for over 60 percent of all city-center trips and half of all daily commutes into the city, are everywhere in Amsterdam. They fill the streets, packed into unsightly metal-framed multistory bike parks and also locked to bridges, railings, and lampposts as a form of urban decoration. In the Netherlands, a country of 17 million people and 23 million bicycles, these vehicles are a key consideration in all urban-design projects, not only in movement, but also in storage.

Aerial view of Amsterdam Central Station and IJboulevard. Photo © Ossip van Duivenbode, click to enlarge.

Amsterdam’s packed center has little space. There is, however, plenty of water, with much of the city built upon wooden piles. Central Station is constructed this way, standing on nearly 9,000 piles, but a new extension goes one step further, building beneath the IJ as well as on the river.

IJboulevard, by VenhoevenCS architecture+urbanism, is a key component of a decade-long Central Station strategy to improve capacity and access. From the outside, it might not seem like much to look at architecturally: a nearly 65,000-square-foot public plaza to the north of the station that offers a moment of calm, with views toward the emerging towers on the facing bank of the IJ. Under the surface, however, lies a far more complex feat of engineering ingenuity.

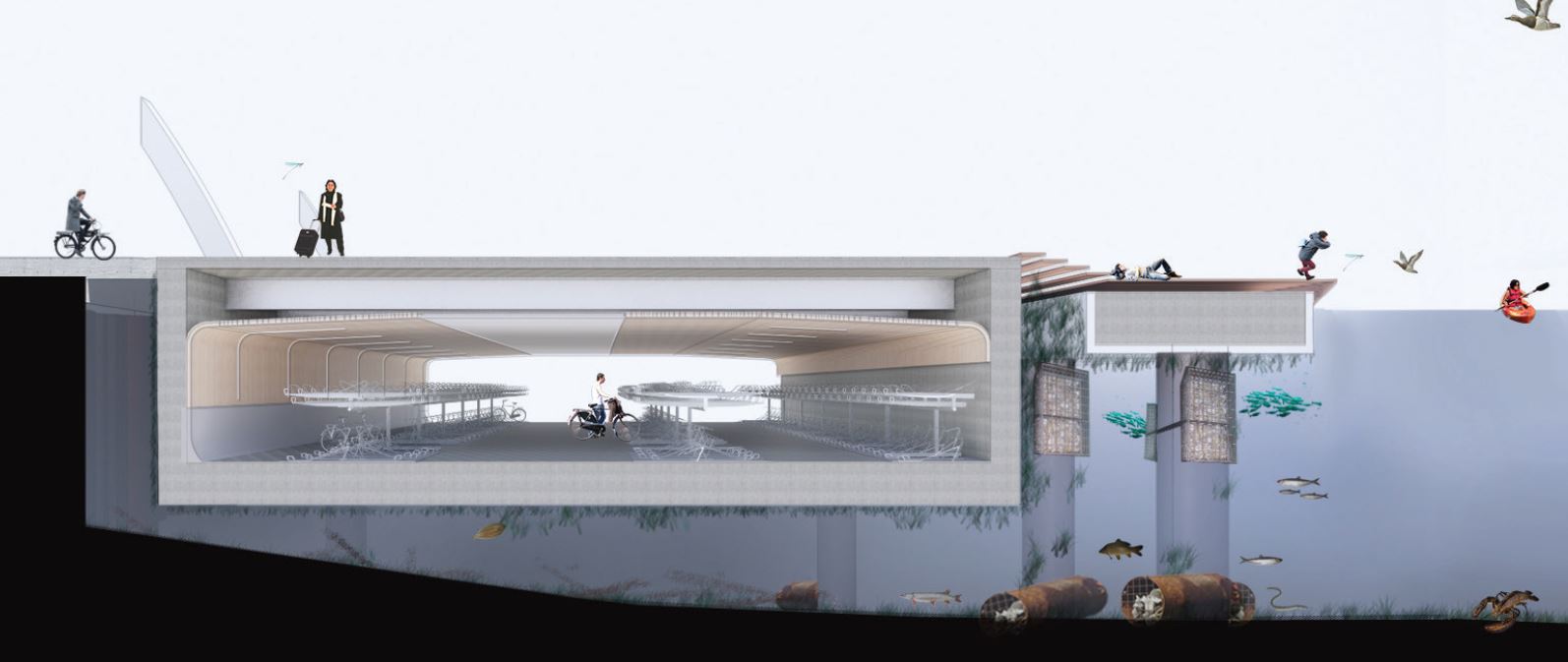

Tucked below the new riverside terrace is a state-of-the-art bicycle storage facility. Four penetrations into the otherwise open paving offer access: two central staircases and, at each end, shallower stairs with ramps for bicycles to be wheeled on. Inside, the neatly detailed and generously open space is a long corridor of continuous double-height bike racks, its gentle curve reflecting the bend of the river, adding to the drama of unexpected scale.

The column-free design maximizes available storage space. Photo © Ossip van Duivenbode

Users enter the facility with a simple swipe of a credit or city-transportation card—storage is free for 24 hours, then roughly $1.50 a day thereafter—and guide bikes to a spot. Cameras and sensors monitor capacity, feeding clear signage and ceiling lights to indicate where users can find empty spaces. The cameras also note bikes that have not been moved after several weeks, alerting staff to remove any that may have been abandoned.

Although a space with an immediate and understandable ease of use, IJboulevard bike garage is the result of an elaborate construction process. The tunnel was formed from three concrete tubes, built eight miles away in a shipyard before being floated to the site on a pontoon. With the ends of each tube closed off by steel sheets, the three components were sunk into the water before being maneuvered into place, carefully avoiding existing perpendicular Amsterdam Metro lines beneath. Then they were joined together, the temporary steel ends of each section cut through to create a single hollow form with room for 4,000 bicycles. VenhoevenCS partner Danny Esselman calls it a “semi-floating situation”—the structure is supported on underwater columns, but the columns require less engineering than if above ground, due to the innate buoyancy.

The underwater facility can accommodate 4,000 bicycles. Photo © Ossip van Duivenbode

A timber promenade at the water’s edge, reached by steps down from the plaza, disguises a solid concrete slab that protects both the bike park and train station in the event of a ship’s veering off course. Underneath both elements, and among the supporting piles, a new aquatic habitat has been created. Formed of wood, coconut mats, porous concrete, and artificial fish nurseries known as bio-huts, the project’s marine landscape was designed in collaboration with DS Landschapsarchitecten to provide surfaces and shelter for aquatic flora and fauna to flourish.

The riverfront promenade. Photo © Ossip van Duivenbode

Esselmen explains that the northern edge of Central Station had historically been its “backside”—a forgotten space once rife with crime and prostitution. VenhoevenCS now proudly refers to the reimagined area as the “city’s balcony.” In the process of creating concealed parking for thousands of bikes, the scheme also enables removal of unattractive bike-storage units at the front of the station, returning 18,000 square feet of outdoor space for pedestrian use.

From its opening in late February, IJboulevard looked as if it had always been a part of the urban landscape surrounding Central Station. Commuters immediately flooded in and out with bikes, tourists flowed from the station to the new riverfront boardwalk to admire city views, and, hidden beneath the water, aquatic life began to build a new home.

Click section to enlarge