Virgil Abloh, who died last November at 41 of a rare form of cancer, was known as a sculptor, a graphic artist, a furniture maker, a fashion designer, and a formidable entrepreneur—a polymathic creative whose Ikea doormats became almost as famous as the the album covers he designed for Kanye West and the menswear collections he created for Louis Vuitton. But first, Abloh was an architect. Trained in civil engineering at the University of Wisconsin and in architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology, where he studied in the Mies van der Rohe–designed Crown Hall, Abloh wove themes of structure, construction, space, and architectural symbolism throughout nearly all of his subsequent work.

The importance of architecture to Abloh is readily apparent within “Figures of Speech”, the sweeping exhibition dedicated to his career on view at the Brooklyn Museum (through January 2023). The show, which debuted at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago in 2019, was redesigned and expanded for its Brooklyn presentation by Abloh, working with curator Antwaun Sargent and designer Mahfuz Sultan, in the years prior to his death.

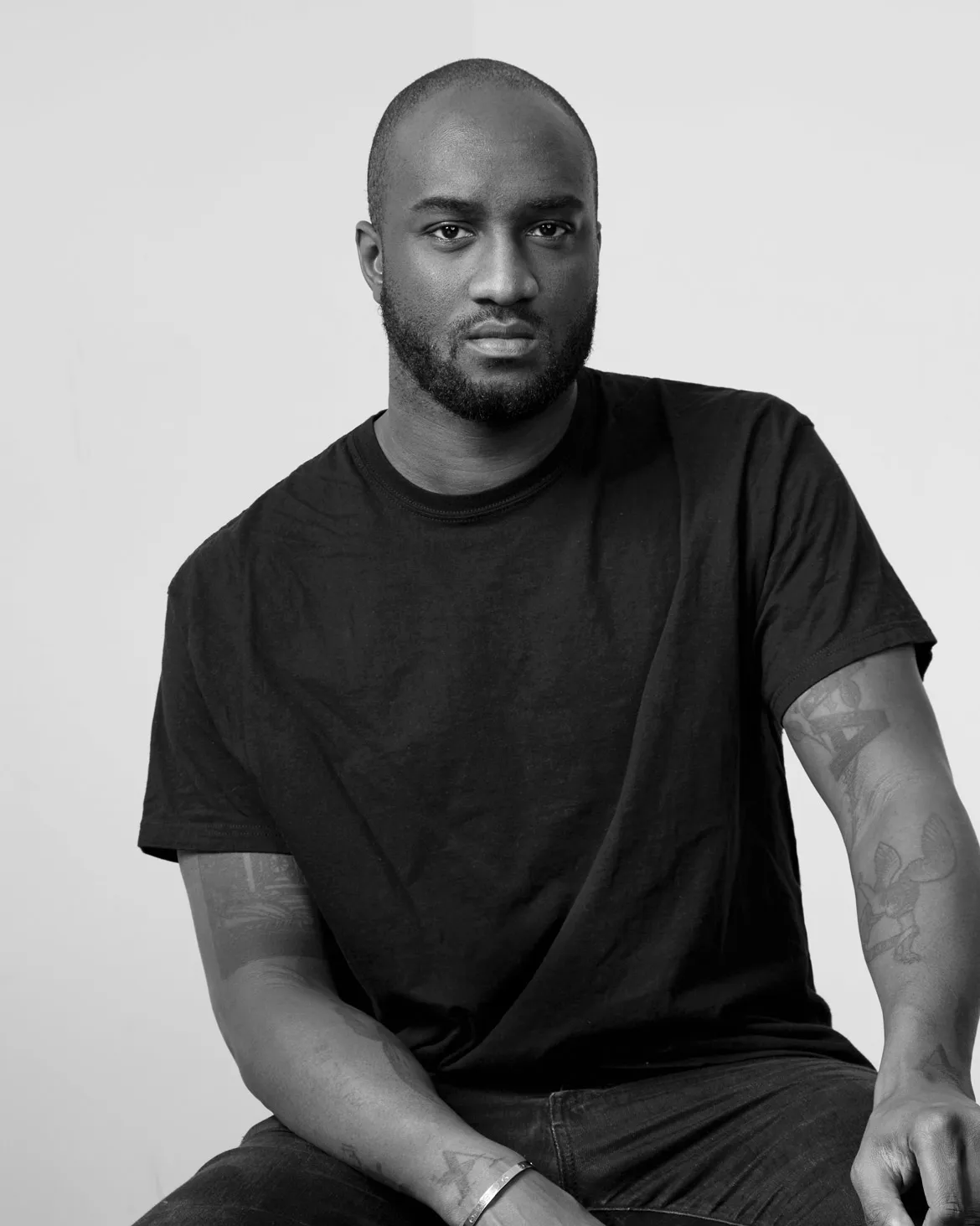

Designer Virgil Abloh, who died last November at 41 of a rare form of cancer. Photo by Fabien Montique

One of the first objects that visitors encounter is a large foam model of central Chicago showing Abloh’s IIT thesis project—a tower that cranes over the Chicago River in order to provide occupants with views of Lake Michigan. The model establishes the importance of Abloh’s architectural training for the rest of the show, while placing his design in conversation with the landmark Chicago towers of Mies van der Rohe, Bertrand Goldberg, and even Jeanne Gang, whose St. Regis tower is included despite having been completed well over a decade after Abloh’s graduation. And the model’s construction—of generic light blue styrofoam apart from his tower, which is rendered in red-tinted acrylic—both emphasizes that the design is a student project and introduces Abloh’s interest in using ordinary materials in unexpected ways.

The emphasis on architecture continues throughout the show. Among more than 100 objects on display are several sculptures referencing architecture; a mural-like wall graphic dedicated to Abloh’s influences that includes images of Chicago landmarks; and a small model, credited to Abloh, Oana Stănescu, Dong-Ping Wong, and Simona Solórzano Gómez, of a store for Abloh’s Off-White fashion brand. Visitors navigate the exhibition architecturally, using a pamphlet containing object labels that refer to the show’s floor plan. An entire section is even titled “Architecture” (Abloh often deployed quotation marks to raise questions about the connotations of words), and many of the objects in it are presented on long plywood tables that refer to both drafting tables and fashion runways: from architecture to fashion and back again.

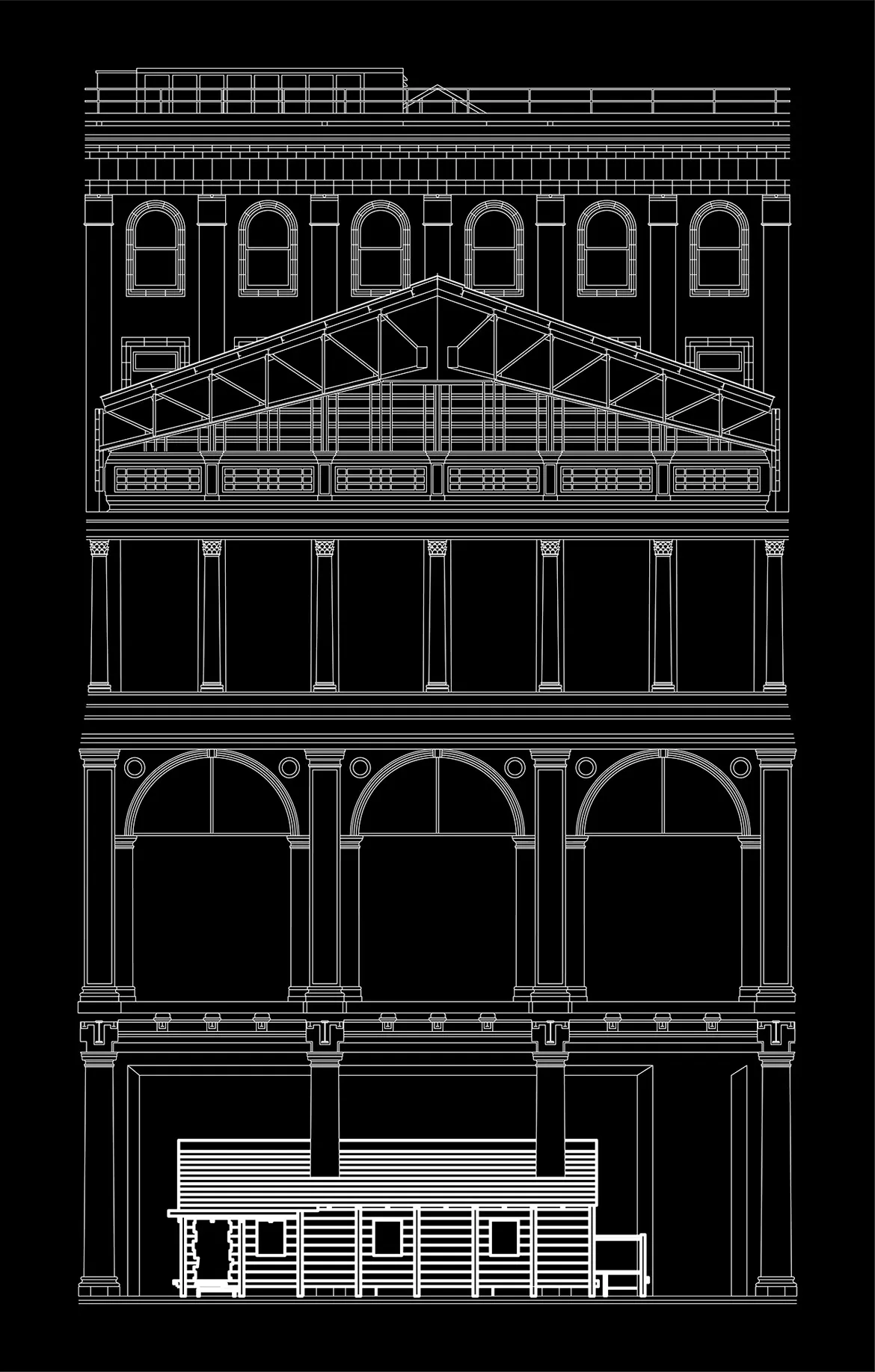

A schematic section drawing of Abloh’s Social Sculpture within the McKim, Mead & White–designed Beaux-Arts Brooklyn Museum building. Drawing © Alaska Alaska

But if Abloh makes a positive case for the importance of architecture, he also casts a critical eye on the discipline’s shortcomings. “Every object is also a critique of the way that architecture has been practiced as a discrete discipline and as a gatekeeping discipline,” says Sargent, the curator. “It says something that Virgil made his career outside of architecture.” And, indeed, Abloh’s many works on display—from sneakers to sculptures to audio systems to videos, many of them created in collaboration with musicians, artists, and even major brands—reflect an impromptu inventiveness and a compulsion to cross disciplinary boundaries that is rarely encouraged in the staid world of architecture.

Abloh’s critique also has a racial dimension. At the literal center of the exhibition is Social Sculpture, a house like wooden pavilion conceived by Abloh in relation to what artist David Hammons once described as “negritude architecture”: “Nothing fits, but everything works . . . It doesn’t have that neatness about it, the way white people put things together; everything is a 32nd of an inch off.” Abloh’s 1,400-square-foot pavilion, which has a pitched roof and a generous porch, self-consciously illustrates Hammons’s description with boards cut to different lengths, inconsistent cladding patterns, and other visible “imperfections.” According to Sargent, Abloh at one point even suggested placing a sign above its door reading “Colored People Only.”

An unreleased sneaker prototype by Abloh for Off-White, created in collaboration with Jacob & Co (2020). Photo © Gymnastics Art Institute

Social Sculpture derives much of its power from its sharp contrast with the surrounding Beaux-Arts museum building, whose Doric columns pass through the pavilion’s roof in several places. Where the museum interiors are relentlessly white and smooth, the pavilion is dark and textured. Where the museum is rigid and formal, the pavilion is homey and laid-back. And where the museum is designed around looking at objects, the pavilion doesn’t tell visitors what to do: it is empty inside, apart from an image from Abloh’s first Louis Vuitton ad campaign and a sound system designed by Devon Turnbull. It invites visitors in to gather formally and informally, with events programmed throughout the exhibit run, and its repudiation of the typical museum environment makes it all the more powerful. In the words of the label, the pavilion is a “representation of Black space, a living monument that holds the potential, through the exchange of ideas, to inspire the creation of more Black space.”

On a recent morning, as music and fashion videos could be heard in the background, visitors sat and chatted along the edge of the pavilion porch. Others casually wandered through its brightly lit interior, examining the exposed structure. Here an oft-mentioned quality of Abloh’s emerges: his generosity. This is a space that is both lively and comfortable—a gift to museum goers—and one that encourages visitors to think for themselves about the broad social themes raised in the exhibition. Abloh’s “mission and his artistic project was to remake space,” says Sargent, and he did so in a multitude of ways across fashion, music, art, and other disciplines. With Social Sculpture, he has posthumously done so in architecture too.