Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego by Selldorf Architects

La Jolla, California

Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego. Photo © Nicholas Venezia

Architects & Firms

On a slope with spectacular ocean views, the Art Center in La Jolla, a neighborhood of San Diego, opened in 1941 in the 1916 villa that architect Irving Gill had designed for newspaper magnate/philanthropist Ellen Browning Scripps. As the venue expanded its mission and collections, the original stuccoed-concrete house, an early example of California Modernism, acquired motley additions. In 1950, local architects Mosher & Drew (M&D) annexed formal galleries and, a decade later, an auditorium, along with other modifications. In 1996, Venturi Scott Brown & Associates (VSBA) reworked the overall organization, adding amenities such as a café, museum shop, and outdoor sculpture garden; the firm also stripped away M&D’s early-1960s front elevation to reveal and restore the Scripps House’s facade. Adjoining it, VSBA’s new elevation echoed the villa’s flat planes and arched openings, traits shared by Gill’s La Jolla Woman’s Club across the street. The reconfigured entry sequence proceeded from a forecourt—featuring a riff on the original colonnaded pergolas that fronted the house and club—into a lobby, crowned by a star-shaped cupola with neon-edged forms, evocative of a starburst or palm fronds. That similarly exuberant Postmodernist spirit infused VSBA’s twin pergolas, with their extra-plump columns on undersized plinths. But after the New York firm Selldorf Architects (SA) set out, in 2014, to rethink and expand the museum yet again, its proposed design eliminated those paired structures. “People could never figure out where to enter the building,” says SA senior project architect Ryoji Karube. (Years earlier, VSBA’s remedies included retrofitting the sequence with neon labels and even encouraging the museum to install a giant topiary arrow pointing to the door.) “Those columns,” Karube adds, “also obscured much of Gill’s facade, which we wanted to celebrate.”

The relocated glazed entrance (top) houses the new lobby (above) and museum shop. Photo © Nicholas Venezia, click to enlarge.

But removing them would prove controversial, eliciting protests from a broader architectural community. This month, the museum reopens—without the disputed pergolas. As for the success of this $105 million overhaul—which enlarged the building to 109,000 square feet, doubling the footprint while quadrupling the gallery space—the jury of public opinion is still out.

The original Irving Gill facade is on full display. Photo © Nicholas Venezia

Pairing SA with VSBA, however, is a curious proposition. Exceptionally Minimalist and understated, principal Annabelle Selldorf’s architecture is the antitheses of her predecessor’s extroverted expressiveness and playful contextuality. In numerous high-profile museums and galleries, including New York’s Neue Galerie (2001) and Frick Collection expansion (2024), her designs defer to the artwork while subtly integrating pre-existing, sometimes historic, architecture. “When we first spoke with Annabelle, she was still emerging—and hadn’t yet done much of that major work in the art world,” recalls Hugh Davies, then director of the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, or MCASD, as the La Jolla institution is now called. “We were intentionally seeking younger, lesser-known talent because we figured ‘starchitects’ wouldn’t give their best effort to a mere addition.” (Coincidentally, Selldorf was chosen last year to rework another VSBA project, at the National Gallery in London.)

Windows in a newly constructed gallery offer daylight and views. Photo © Nicholas Venezia

Just as MCASD had hired VSBA to work with existing parts, the museum was, once again, not looking to start over from scratch, or only with the Scripps House. “Building in La Jolla is extremely challenging,” explains MCASD director Kathryn Kanjo, who succeeded Davies in 2016. “The only way, for example, to get the ceiling heights needed for big, contemporary artwork was by converting the auditorium into gallery space—since that ‘nonconforming’ structure had been grandfathered, bypassing current height restrictions.”

The previous architectural interventions also brought cumulative challenges, including diverse ceiling heights and a massing hodgepodge, particularly on the building’s “back,” or west, side. Though the primary entrance has always been from the east, along Prospect Street—a key avenue, with a cluster of Gill-designed buildings—the long, ocean-facing west elevation is highly visible from the picturesque waterfront Coast Boulevard. On that side, the steep site’s irregularities had inspired additions skewed at various angles from the original house. VSBA addressed many issues—including connecting the terraced ocean-facing sculpture garden to the museum, for instance, while giving the entry side, on Prospect, a stronger urban presence—but the architects’ planned gallery wing was never built, and fixing such a piecemeal building was probably impossible without significant demolition.

1

Some galleries, and the new event space, have views to the water (1 & 2). Photos © Nicholas Venezia

2

Now, in some respects, SA’s quiet Minimalism provides a foil for not just the art but also the eclectic architectural elements. “It was important,” says Selldorf, “to knit together the different parts cohesively, while still preserving their distinctive and recognizable qualities—letting them tell the story of the museum’s evolution.” Rectilinear and clean-edged, her addition extends the building southward, meandering in plan around a large existing ficus tree. Instead of giving the disparate parts a single unifying color or surface treatment, “we chose not to dip everything in the same batter of stucco,” she says. “As with the forms, we wanted the materials to articulate separate readings.” So her addition introduces an exterior palette of board-formed concrete, with sand-toned travertine and extensive glass, notably in the mostly transparent entry “cube” housing the new lobby and museum shop. Sited at a T-intersection, where Silverado Street—leading from the town center—meets Prospect, the relocated entrance “makes sense urbanistically and for interior flow,” argues Selldorf. “With 80 percent of the galleries now in our addition, the building’s center of gravity shifted to that end.”

Parts of the new exterior feature sand-toned travertine. Photo © Nicholas Venezia

Inside, contrasting floors—terrazzo, wood, and concrete—distinguish the building’s chronological phases. Smoothly navigating different ceiling heights, SA balanced light, views, and proportions, easing transitions from space to space. In the former auditorium, the gallery soars to 20 feet, with another one tucked beneath it. The fluid interiors—all with seismic and sustainability upgrades—invite multiple circulation paths, unlike the former “snake” of galleries, as Davies describes it, which not only limited visitor routes but often required closing every exhibition space just to reinstall one. The addition also follows the topography, stepping downhill with mezzanine overlooks, outdoor decks, and windows orienting visitors to the seascape or neighborhood landmarks. The new galleries are spacious and airy, and—while such familiar features as semi-industrial surfaces and concrete T-beams overhead are hardly unique—MCASD’s impressive collection, dedicated to work since 1950, looks good there.

The addition follows the topography, stepping downhill with mezzanine overlooks, outdoor decks, and windows to the seascape. Photo © Nicholas Venezia

Selldorf successfully defended preserving VSBA’s starburst lobby (known as Axline Court), whose new roles will include that of reception hall for the many visiting school groups. Without any ticketing counter “or other distractions, its sky and ocean views are unobstructed, and the design is so much clearer,” says the architect. “It’s an artful space”—and one that now reads as a quasi-sculptural installation.

Axline Court, with its starburst ceiling, was preserved. Photo Courtesy Selldorf Architects

As for the twin pergolas, “I fought very hard to keep them, despite board opposition,” recalls Davies. “It was the biggest battle I lost within the museum in 33 years as its director.” He later salvaged one pergola by personally (at the time, anonymously) funding its relocation, a few yards away, to the local historical society’s backyard, where it now resides. “Much as I regretted losing those colonnades,” he concedes, “I now think the fully revealed Gill facade looks great.”

The pergolas, which shaded café tables, enjoyed a devoted following (even among those who dubbed them “Pillsbury Doughboy columns”). It’s easy to imagine how those garden structures could have remained, almost as sculptural pieces. But a far less reversable loss is VSBA’s arched facade, now truncated, leaving two side-by-side arches of different heights—an almost meaningless fragment, stripped of its original rhythm. (Even an unbroken row of three arches could have retained it.)

On the interior, the renovation seems transformational in improving functionality and the art-viewing experience, but the exterior is less compelling. Once the Scripps House began gaining accretions, it ceased being an “object”—a singular iconic form. But, even accepting the entire building as a rambling composite or, as Selldorf puts it “a community of built forms,” the final exterior results—while veering away from being a splashy ego statement—don’t feel particularly distinctive. On the west face, SA did clear away messy back-of-the-house elements, replacing an open loading dock with a state-of-the-art enclosed one and eliminating the auditorium’s exterior egress stair. Now the hillside massing includes a new multipurpose event space, with panoramic views and an independent entrance. While the ocean-facing elevation has become crisper and more deliberate, it is still, perhaps inevitably, a bit of a jumble.

“This building’s odyssey has spanned 106 years,” says Davies. “In the end, it’s really the visitors who determine the success of a museum’s redesign. It’ll be illuminating to see where they pause, what they gravitate toward, how they occupy the space. It will be wonderful to see it full of people.”

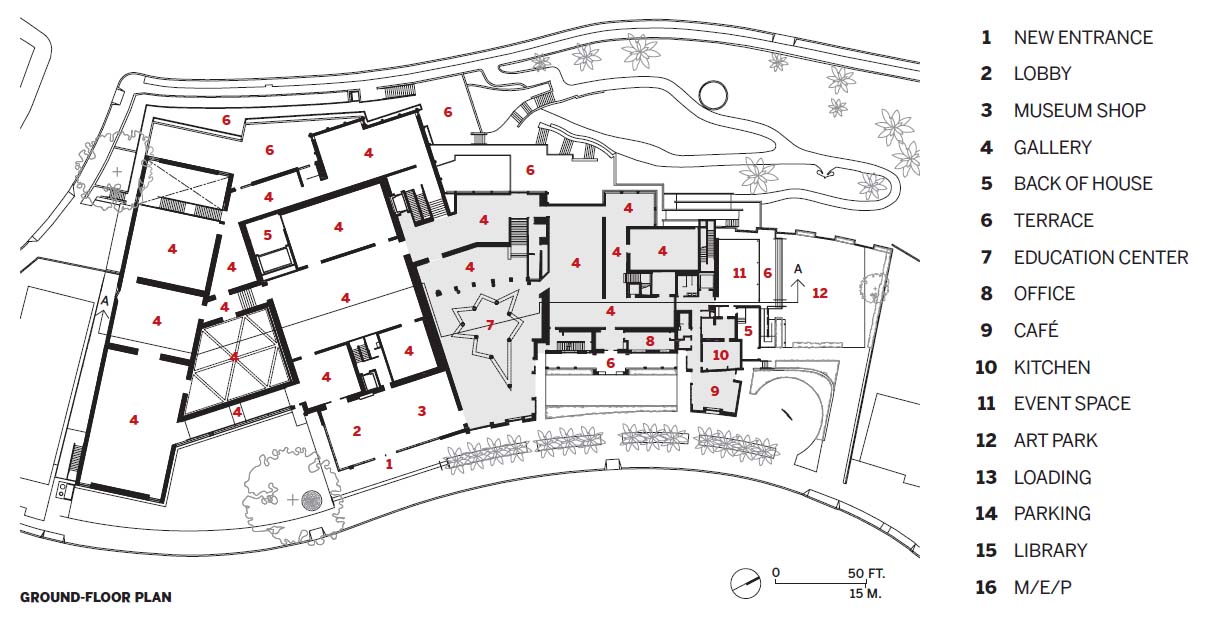

Click plan to enlarge

Click plan to enlarge

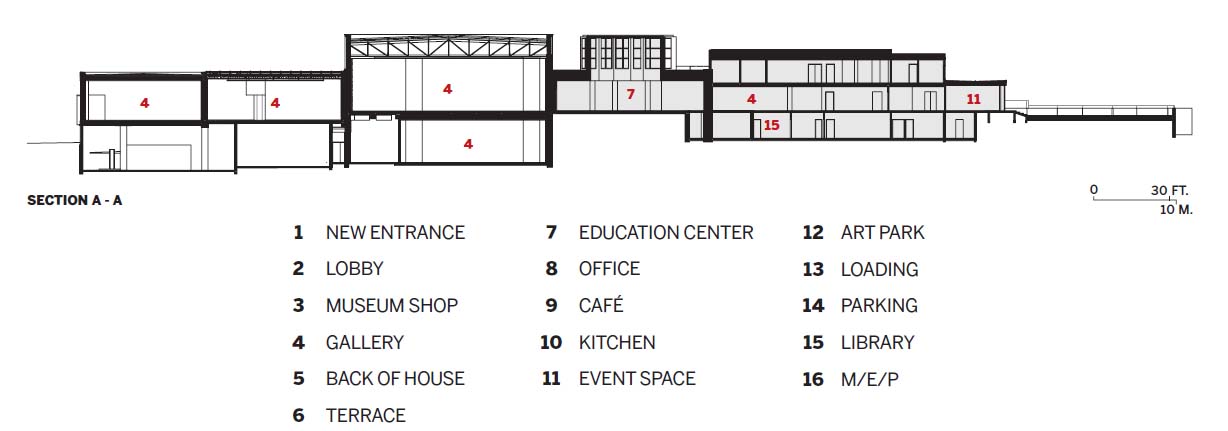

Click section to enlarge

Credits

Architect:

Selldorf Architects — Annabelle Selldorf, principal; Sara Lopergolo, partner in charge; Wanda Willmore, project manager; Ryoji Karube, senior project architect; Corey Crist, architectural designer

Executive Architect:

LPA

Architect of Record:

Alcorn & Benton Architects (approvals)

Engineers:

Guy Nordenson and Associates (structural design); Simpson Gumpertz & Heger (structural); Buro Happold (m/e/p); LPA (civil)

General Contractor:

Level 10 Construction

Consultants:

Purcell + Noppe + Associates (acoustics); Renfro Design Group (lighting)

Client:

Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego

Size:

109,000 square feet

Cost:

$105 million

Completion Date:

April 2022

Sources

Travertine:

TerraCORE Panels

Curtain Wall:

Oldcastle BuildingEnvelope

Glass:

Guardian Glass

Skylights:

Viracon

Metal Doors:

Panda Windows & Doors

Hardware:

Assa Abloy

Elevators:

Otis

Acoustic Baffles:

Sky Acoustics

Interior Ambient Lighting:

Edison Price Lighting

Plumbing:

Toto