Architecture Schools Adapt to an Uncertain Future

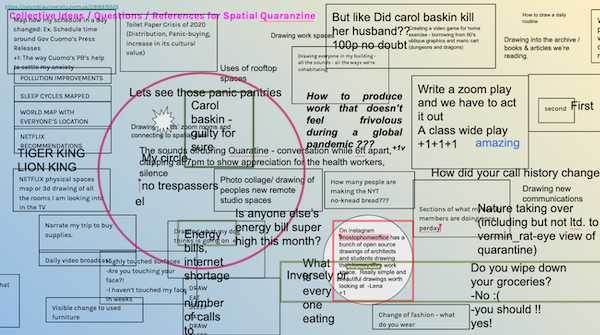

Students and faculty interact via video call during a session of the spring 2020 GSAPP course Architectural Drawing and Representation II, taught by Dan Taeyoung, Violet Whitney, Quentin Yiu, Lexi Tsien-Shiang, and Andrew Heumann.

Image courtesy Columbia GSAPP

For the 25,000 students in accredited architecture programs nationwide—plus those studying landscape architecture, interior design, historic preservation, planning, and related disciplines—the spread of COVID-19 has meant a sudden mid-semester pivot from hands-on studios and field work to remote learning. While technology has eased aspects of the transition, the current crisis has shed light on inequities in architectural education, leading some to rethink what design schools might look like in a post-pandemic world.

For administrators, the first priority has been making sure students are safe and have access to the technology required to complete their coursework online—even, in the case of the Yale School of Architecture, shipping laptops to students. But now that students have left campuses, other challenges have come into focus.

“It’s like we’ve lifted the lid on what social human life really is,” says Michelle Addington, dean of the University of Texas at Austin School of Architecture. As the coronavirus spread and social distancing became compulsory, she heard from faculty, staff, and students struggling to balance school work with new care-taking responsibilities. Those things “didn’t have to come into play before, but should have,” she says. “I think this situation has opened a crack into that.”

While technology has been essential, the pandemic has also revealed its limits. Meejin Yoon, dean of Cornell Architecture, Art, and Planning (AAP), says that before, there was a sense that technology was an equalizing force. “But having moved to remote instruction, we’re finding that equity is a major issue.” The sudden shift—“a push, not a pull” into online learning—has highlighted a number of inequities. Spread across “every time zone,” the now home-bound students face novel challenges, from a lack of high-speed internet or dedicated workspaces, to new childcare and homeschooling duties. “How we can experiment with architectural pedagogy and mediums and formats,” asks Yoon, “but in a way that’s as equitable and accessible as possible?”

Many academics have responded with a new sense of openness, says Deborah Berke, dean of Yale Architecture. “Learning from this balance between rigor and generosity of spirit makes expanded forms of education more possible,” she says. For some institutions, pursuing balance has meant scrapping the pressure of grades. “We’re treating this situation as an opportunity to explore, invent, and try new things,” says Andrew Heumann, who co-teaches 83 students at the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation (GSAPP). His class has taken a playful approach, creating a “Quaranzine” and collaboratively making images within the now-ubiquitous video conferencing grid. And yet an important element of personal contact is missing, he says. “I can’t get as complete a picture of everything that’s happening with my students in a moment like this.”

Keeping that sense of connection has been key for Felix Heisel, who teaches a first-year undergraduate architecture studio at Cornell that shifted from hand-drawing and material exploration to digital representation. But how can the group experience be retained? “We can give them instruction, but the input they get from classmates to their left and right is missing right now,” he says.

For those about to graduate, pedagogical limitations are compounded by fears about how the post-coronavirus economy will affect firms’ ability to hire.

“I’ve gone through all the stages of grief to acceptance at this point,” says Allison Fricke, set to graduate from Columbia GSAAP with dual master’s degrees in architecture and historic preservation. For students like her, the pandemic has meant the cancellation of studio travel, the end of access to libraries and fabrication labs, the need to hold final reviews via video, and the abandonment of commencement celebrations—in addition to frozen or non-existent job offers. “This really is an anti-climactic end to it all.”

The spiraling economy is something schools have to address head-on. “My philosophy is it does not serve our students to give them unjustified optimism in a state of great uncertainty,” says Phil Bernstein, an associate dean at Yale. He organized a panel of practitioners who had entered the workforce during previous downturns to speak with students, whose career prospects are less likely to follow traditional paths than recent graduates. “As educators, we’re going to have to be super clear about why and how we are training the next generation of architects—and how they’re relevant in the post-pandemic world,” he says. “If we don’t, given the cost of an architecture education these days, we’re going to see a lot of empty seats in studios.”