Architects & Firms

In 2014, Berlin-based Sauerbruch Hutton won a competition to reenvision the site of the Postscheckamt—a 1970s commercial tower with a sprawling single-story plinth—in the city’s Kreuzberg neighborhood as a dense mixed-use residential quarter. A few market-driven revisions (and passings of client hands) later, the enclave now partially goes by Die Macherei, or “the makery.” It is the third such community in Germany to operate under the moniker, providing office and coworking spaces as well as retail and gastronomic offerings, with plenty of housing next door.

As part of the master plan, the firm situated six mid-rise apartment towers deep within the 7.5-acre site, but, fronting Hallesches Ufer (a road that runs along the Landwehr Canal), it placed three signature office buildings. From east to west, they are: M40, a champagne-colored mass-timber structure designed by KEC Architekten; M50, the new iteration of the 23-story-tall Postscheckamt, which is undergoing a gut renovation and full reclad by Eike Becker; and M60—undoubtedly the gem in the ensemble—an eight-story structure designed by Sauerbruch Hutton.

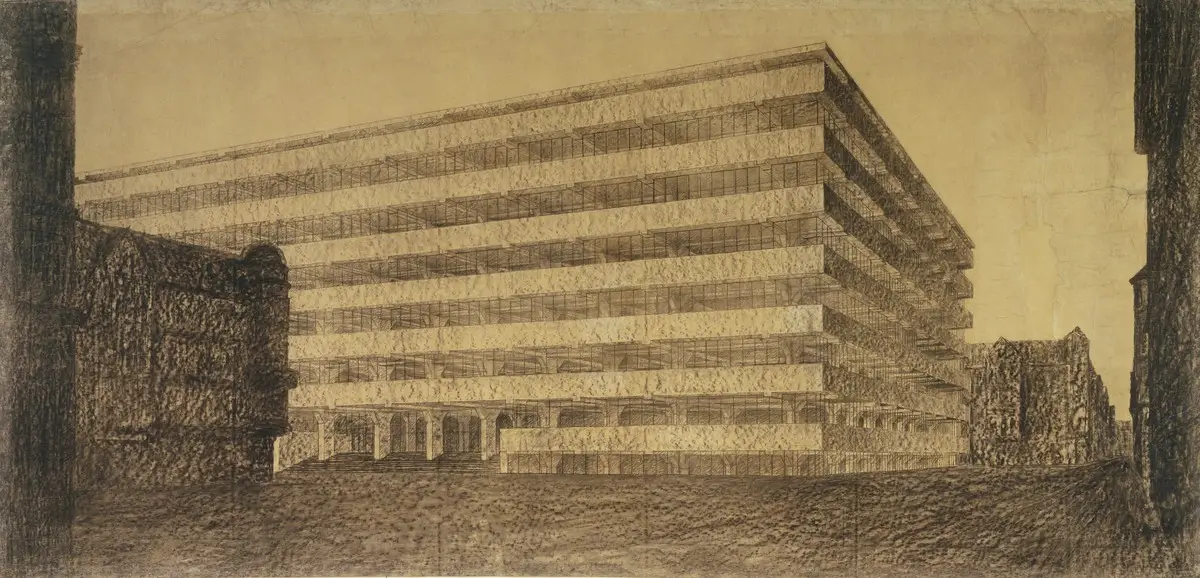

In its simplicity and clarity of form, M60 shares a familial resemblance with Mies van der Rohe’s Concrete Office Building. This unbuilt proposal for central Berlin, dating to 1922–23, freed the facade from the task of structural expression by bringing perimeter columns inside the envelope, producing long horizontal bands of concrete with ribbon windows spanning between them. “Maximum effect with the minimum expenditure of means,” Mies wrote at the time. Despite its modernity, the project also showed his predilection for classicism, from the emphasis on axial symmetry to its thin floating cornice.

1

2

A rendering of M60 (1) shows the clarity of form and horizontal banding that it shares with Mies’s Concrete Office Building (2). Images © Sauerbruch Hutton (1); Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by Scala / Art Resource, NY (digital image, 2), 2024 Artists Rights Society, New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn (art, 2), click to enlarge.

A similar purity undergirds Sauerbruch Hutton’s building. But, up close, it has an abundance of interesting details to offer. Like many of the firm’s most recognizable projects, M60 prominently features architectural terra-cotta, but it is more sobering than the polychromatic GSW Headquarters nearby and Italy’s M9 Museum District. Its faceted glass-and-ceramic facade reflects a pixelated version of the city to passing pedestrians, cyclists, and rail commuters alike (the elevated U-Bahn station Möckernbrücke is across the street). Within the warp and weft of Kreuzberg’s postindustrial urban fabric, it feels both at home amid abundant loft spaces and glazed bricks, but—with glinting emerald-green panels—M60 is also something of an ever-changing jewel box.

A faceted facade (top of page) wraps M60, which faces an elevated U-bahn station (above). Photo © Jan Bitter

Not only do these ceramic spandrels zigzag and terminate in bladelike corners, but individual units (of which there are nine different types) feature vertical corrugation. Their green cast takes on varying hues depending on the light, while subtle dappling adds visual texture. “NBK is really willing to test glazes,” says project partner David Wegener of the terra-cotta manufacturer. “They managed to achieve this handmade look, even though production is fully computerized.”

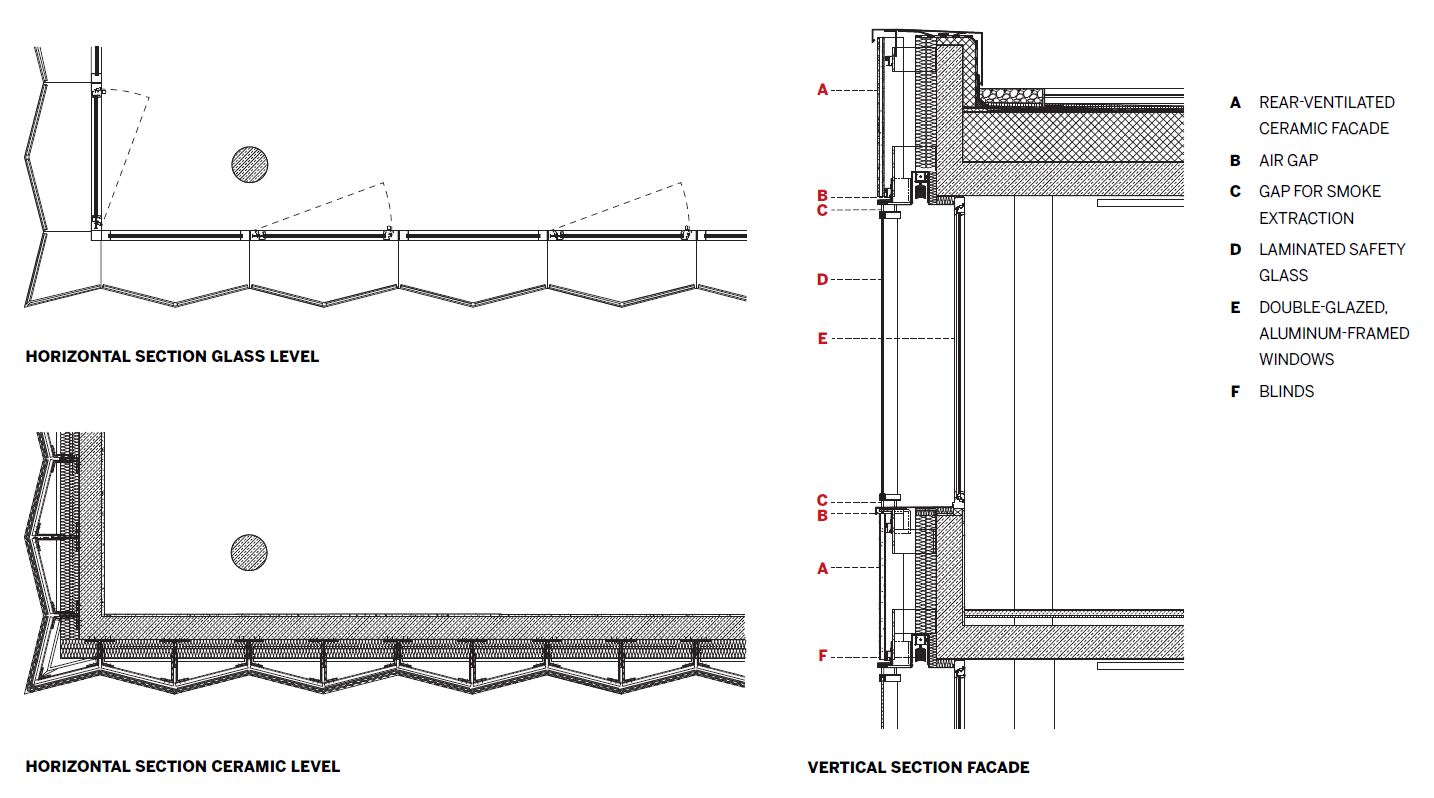

These units are, importantly, not permanently affixed to the facade with an adhesive, or even bonded together with mortar. Rather, they’re individually hung, a process that is more expensive and time-consuming but also more sustainable in the long term. Wegener recalls asking the team, “What is the right approach for this typology during the Bauwende”—a German word without a direct English translation that encompasses the profession’s current shift toward circularity and other sustainable practices—“when a client insists on using concrete?” Sauerbruch Hutton’s solution: radical deconstructability. The wall system can be disassembled into reusable constituent parts, something adhesives would have prevented. Binding agents also affect an envelope’s breathability, Wegener explains. “It’s like tiling a building from the outside, which, from a physics perspective, is quite bad.”

Gaps between the facade’s outer panes promote airflow. Photo © Sauerbruch Hutton

The faceted geometry comes with other benefits as well. The bands of glazing comprise an outer layer of angled, coated panes spaced ¾ inch apart, reducing acoustic reverberation from passing trains and solar infiltration, with an inner layer of operable windows. The ventilated cavity between them helps regulate temperature, exhausts smoke in cases of fire, and conceals an automated external-sunshade system.

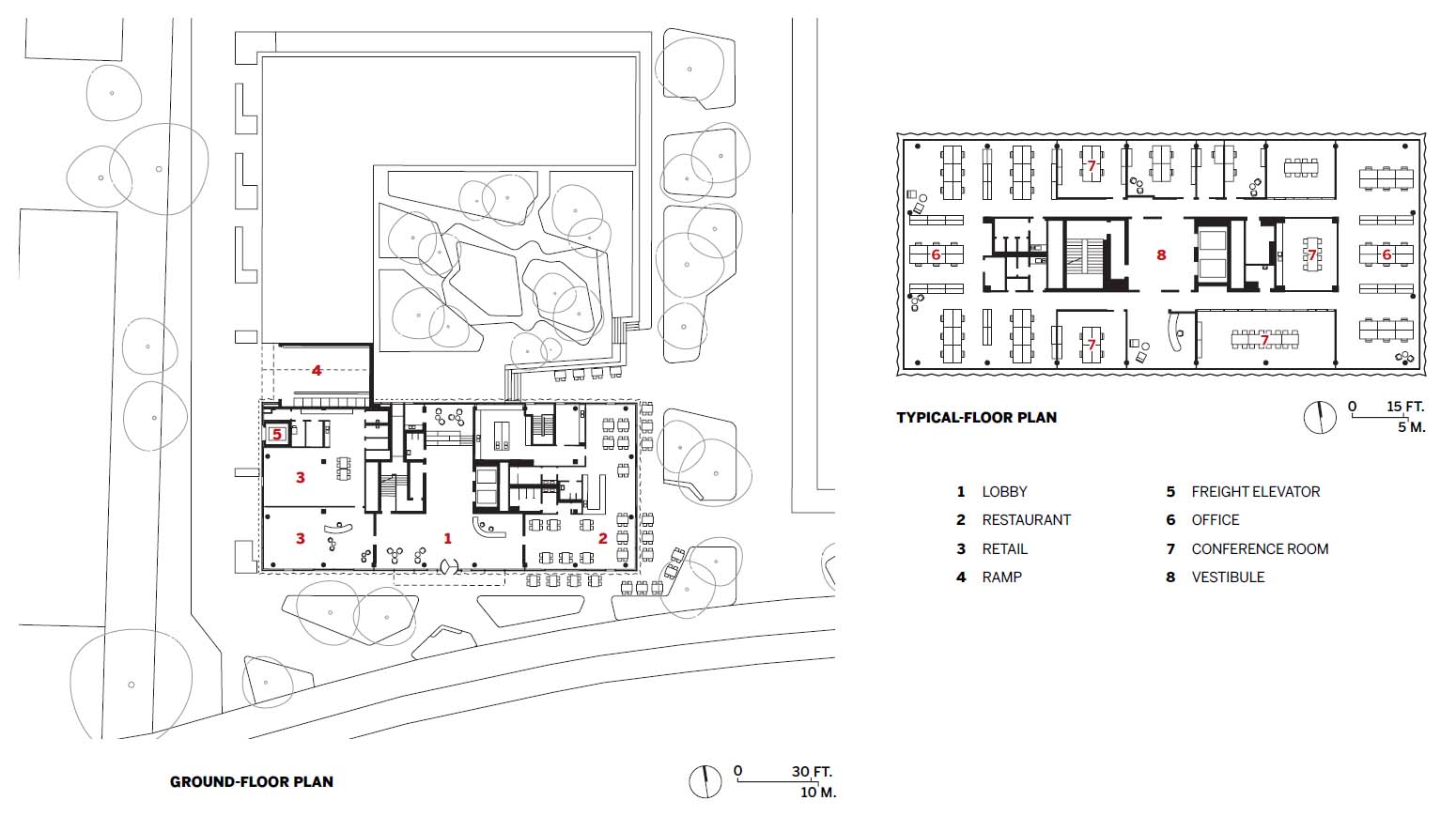

A single bay of the facade spans about 4 feet (precisely 1.25 meters), which affords economical space planning inside. “It is a standard measurement for a two-bay-wide office, which developers here love,” says Wegener. “Sometimes it results in an awkward facade proportion,” he adds, but M60 indeed cuts an elegant figure. Inside this dazzling wrapper, white-concrete terrazzo includes aggregate in hues of emerald, charcoal, and salmon. The simple office levels—planned with structural columns centered every 20½ feet (6.25 meters) around a compact core—can be easily divided in half and have been minimally fitted out while they await lessees. The ground floor will accommodate a restaurant and retail spaces.

Looking for a reprint of this article?

From high-res PDFs to custom plaques, order your copy today!

Construction continues at the Die Macherei site. Photo © Sauerbruch Hutton

It will be a while, though, before Die Macherei is completed and the streetscape fully activated—Sauerbruch Hutton’s is the first building of the master plan to open its doors. But, even as work remains, M60 signals what’s ahead and shows that even economical forms can pass with flying color.

Click plans to enlarge

Click details to enlarge

Credits

Architect:

Sauerbruch Hutton — Matthias Sauerbruch, Louisa Hutton, David Wegener, Mareike Lamm, Ilona Priwitzer, Marie-Sophie Starlinger, Alina Tapley, Lou-Salome Bienvenu, Aleksandra Wypior, Maria Silvestre, Mengyuan Cao, Marc Stellmach

Engineers:

Haustechnik Planungsbüro Schumacher (electrical, mechanical); Werner Sobek (structural)

Consultants:

SINAI (landscape); HHP West Beratende Ingenieure (fire safety); Müller-BBM Building Solutions (building physics)

Contractors:

Hirsch & Lorenz Ingenieurbau (shell); TM Ausbau (interiors); Medicke (facade); Rud. Otto Meyer Technik (m/e/p)

Client:

Art-Invest Real Estate Management

Size:

112,395 square feet

Cost:

Withheld

Completion Date:

September 2024

Sources

Cladding:

NBK Keramik (ceramic)

Doors:

Domoferm (metal); Schörghuber Spezialtüren (wood); Feuerschutzvorhang SIMON PROtec Systems (fire-control)

Hardware:

Winkhaus Gruppe, dormakaba Deutschland

Flooring:

Casalgrande Padana (tile); Lindner (raised flooring)

Lighting:

XAL, Wetec